In the winter of 2013, Quentin Bajac and LaToya Ruby Frazier had their respective major New York debuts, of sorts. That January, Bajac became the Chief Curator of Photography at The Museum of Modern Art; he had previously worked in Paris—first at the Musée d’Orsay and then at the Centre Pompidou. During the 86-year history of MoMA, there have been only four chief curators of the photography department: Beaumont Newhall, Edward Steichen, John Szarkowski, and Peter Galassi. Each of these curators altered the course set by his predecessor. Since joining MoMA, Bajac has explored the relationships between photography and other mediums in addition to assembling Photography at MoMA: 1960 to Now, the first book since 1973 to highlight the museum’s catalogue of photography.

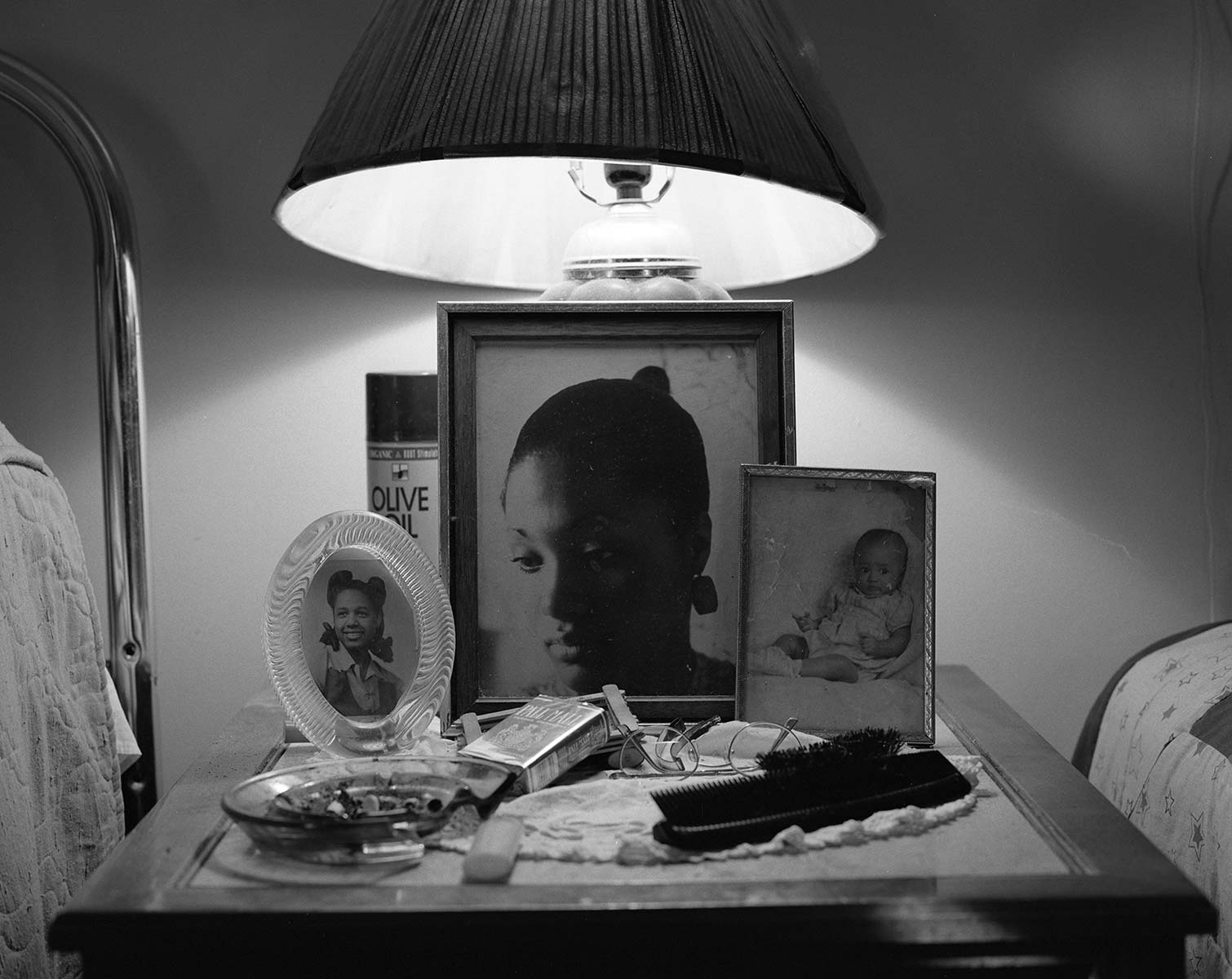

Just a couple of months after Bajac joined MoMA, Frazier had her first institutional solo exhibition, A Haunted Capital, at the Brooklyn Museum. Informed by documentary practices from the early 20th century as well as conceptual art and performance, Frazier explores the intricacies and particular histories of place, race, and family in work that is a hybrid of self-portraiture and social narrative. Her hometown of Braddock, Pennsylvania, a once-thriving steel town, forms the backdrop of her images, which make manifest both the environmental and infrastructural decay caused by postindustrial decline and the lives of those who continue to live amongst it. Last fall, she won the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship, often referred to as the “Genius Grant.”

The formidable pair discuss the history and future of photography at MoMA, the documentary tradition, and the changing boundaries between art and photography today.

Above The Fold

Spring/Summer 2018 Through the Lens of Designer Erdem Moralıoğlu

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

On the Road

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

LaToya Ruby Frazier—I was recently at the Pompidou and something I admired about it, that I don’t see so much here at institutions in the U.S., is the way that the permanent collections are handled. Something that made me really happy was when I saw—in the permanent collection—László Maholy-Nagy’s films with works by Brancusi. There was a corridor tucked in the back which laid out their relationship. You’ve talked about branching out into all these different relationships between mediums and artists’ approaches, to widen the conversation. Could you talk a little about that? I thought the Pompidou collection was far more extensive and elaborative on the histories and relationships between artists and mediums. Will it happen for MoMA under your direction?

Quentin Bajac—The Pompidou and MoMA have different histories. The Pompidou, right from the start, had that idea of a multi-disciplinary or even inter-disciplinary display of the collection. Whereas MoMA quickly moved away from Alfred Barr’s initial idea of having a very multi-disciplinary approach in the late 20s and 30s. It seems that today we’re reopening that debate and have a new generation of curators who want to move towards a more integrated—if not fully integrated—display of the collection. We are experimenting with finding new ways of showing the collection and having that dialogue between mediums and disciplines. The expansion of the museum is planned to open in 2020, so it’s a good time to experiment and to see where we go. I think that we should have both medium-specific galleries and also some galleries where we can have that dialogue between painting, sculpture, photo, film, video, architecture, and design. We already do it on the second floor in the contemporary collection—also in many cross-disciplinary shows in the past. Why not also try to do it on the fourth and fifth floors, which are devoted to the historical part of the collection?

LaToya—You have talked about [cultural critic, Siegfried]Kracauer’s idea of a “blizzard of images” as an overwhelming sense where we lose our understanding of reality because there is such an overflow of images and people are so inundated. I want to take a cautionary position on that. I’m not sure I believe there are so many images in the world that institutions like MoMA can’t hone in and find photographers who are doing things that speak to the history of photography or to the new modes, or find photographers who are still dealing with the history that has come from people like John Szarkowski, Peter Galassi, or Edward Steichen. Have we gone so far in contemporary photography that documentary work—artists who are working in conceptual documentary and trying to understand the world and reality—can’t still be part of the conversation?

Quentin—No, I don’t think that it can’t. In [the exhibition] Ocean of Images: New Photography 2015, you find photographers that could be considered documentary photographers and have that kind of conceptual documentary approach. David Hartt’s work, which consists of not only photos but also videos and installation, is in a way a straight series of documentary photography. Or a photographer like Lieko Shiga, whose series on post-tsunami and post-earthquake Japan is also deeply rooted in a kind of Japanese documentary tradition. There is no technological determinism, and there is still of course space for these kinds of documentary approaches. Also in a very direct way from Basim Magdy to someone like Indrė Šerpytytė. They are all talking about documenting the world in different ways.

LaToya—I’m also speaking more specifically about how MoMA is responding to current events that are facing the country. For example, when you look at the Photo League, it’s incredible because of the period that it happened in, right? Jewish families coming to New York City, photographing life, looking at street photography, understanding the cultural landscape at that moment. I wonder if MoMA has gone so far in the direction of connecting to the art world that it is removing and diminishing photographers that want to look at the everyday. Whether it’s the mundane, the political climate, or current events—will that type of storytelling or narrative and politic come back into some of these shows? We haven’t seen a show like that for a very long time. There are touches on it when you’re pulling from the collection, but there is so much happening right now in the country that I’m always dismayed when I don’t see curators organizing shows that really are directing the current climate. It seems like a missed opportunity.

Quentin—Again, looking at New Photography, when you have a look at some of the works included, maybe they don’t deal directly with the American situation, but deal with history. Basim Magdy deals with some issues related to the Arab Spring, the loss of utopia following the Arab Spring. I can hear what you’re saying about the American perspective, which would not be represented enough in MoMA’s recent shows.

LaToya—I’m also not just saying that it has to be American, because we’re faced with the inequalities of the global economy—it is a worldwide issue. I would hope to see some of that type of content and subjectivity come back to MoMA. We talk about categories and conceptual ideas. I want to see some more of these realities percolate through some of the exhibitions. These are uncomfortable times, and it’s so urgent that these matters are addressed. I’m curious to hear what you see your contribution being, in contrast to your predecessors.

Quentin—I am trying to foster dialogue between photography and the other disciplines or mediums at MoMA. I’d like to break the barriers between the departments and engage in a more interdisciplinary or cross-disciplinary display of the collection. Also being more open to all the many different forms that the photo can take: a print, a book, a zine, a video still, etc. That’s taking into account the very specific history of photography at MoMA. I also hope to be more international, building on Peter Galassi’s work, but I think that we should open our vision even more. Did you see the recent Walid Raad exhibition, which is now at ICA Boston?

LaToya—Yes. Walid Raad is a quintessential artist of my time. His investment in building a story around himself as a person and as an artist—the way he deals with narrative but broadens it to these larger questions of the global economy and politics within art and commerce—really speaks to me. I was excited to watch him do a live performance. That is something you seldom see with artists who work with photography—the fact that the artist is just as much a component of the art.

“I am trying to foster dialogue between photography and the other disciplines or mediums at MoMA. I’d like to break the barriers between the departments.”—Quentin Bajac

Quentin—It’s a great lecture performance with a great mix of almost stand-up comedy within it. Walid has a sense of humor. I’m interested in the fact that you’re interested in Walid’s work because, in a way, the narratives that he builds are very different from your own.

LaToya—Walid and I come from two very different places and times. And again, what makes artists and their work interesting is the story around the artist and their art-making. He’s speaking to his own upbringing, politics, and identity. That’s what speaks to me and gives me an understanding of how I might weave all of these different narratives together—whether fact or fiction—and how those come into play in different types of histories or economies. This is why he is important for me in terms of his structure and his approach and his practice.

Quentin—One of the great singularities of your work today is that it’s so—I’m not using this in a pejorative way—offbeat. You stick to a rather traditional or old-fashioned vocabulary, that of the medium-format camera and black-and-white print; this is your main vocabulary. In one interview you talk about a “20th-century medium.” I like the idea of you talking about a 20th-century medium that would be a straight documentary vocabulary—a term to use if we don’t have any better word.

LaToya—Again, I’m speaking to the place and the origin where I started. It’s become this conversation around these movements from 30s documentary work into this movement of straight photography out of the 50s into the movement of the New Topographics into the movement of the Pictures Generation. I’m moving in between all these movements, speaking to them, filling in the gaps that I see, bringing in my own personality and narrative, coming out of a post-industrial landscape. Coming from Pittsburgh and a small, steel-mill town, I can’t overlook the tradition and legacy that was already there. My forefathers are Walker Evans, who documented in the region—we’ve seen his industrial images from Bethlehem—or Lewis Hine. If it wasn’t for the Pittsburgh Survey—Hine’s survey on the conditions of workers—we wouldn’t understand what working class life was and what those conditions were. Then W. Eugene Smith was commissioned to do a series of hundreds of photo-essays for the bicentennial of Pittsburgh. So there’s already a rich legacy I’m looking at and speaking to. It’s not that I’m offbeat, but that I’m committed to continuing the lineage that came before me, fighting for that vitality and relevancy and trying to keep it going in a post-industrial society.

Quentin—Another aspect of your uniqueness is your belief that photographs are still able to change the world. You’re going back to the idea of the concerned photographer. I have the feeling that some photographers in the 70s, 80s, and even 90s tried to move away from that. Some people, mostly in your generation, seem to have no problem with being considered as concerned photographers.

LaToya—That’s not a term that I would use. I consider myself a conceptual documentary artist. These are the terms that come near the topics and categories of my practice. Even when you look at my book, The Notion of Family, the impetus for and the conceptual framework around it is questioning, deconstructing, and elevating the notion, history, and argument around social documentary. What were the things left out? What were the troubling paradigms that I saw in it? One of the paradigms and structures that spoke to me immediately when I first saw Gordon Parks’s images of Ella Watson or Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother or any of Walker Evans’s images is the fact that the government or corporations could commission these photographers to go in from the outside and create the subject and narrative around people that were capable of speaking for themselves. It’s not that I see myself as a concerned journalist or documentarian. I’m pushing back very much at how the Pictures Generation resisted and questioned the media’s representation of their particular moment. Growing up after the Reagan administration and watching the way my experience was being televised—the collapse of the steel industry or the war on drugs—the way it was being mediated was very problematic for me as a teenager who had to absorb these very fractured images of what my daily reality was like. I’m trying to weave this other narrative around what I see as the dominant narrative, which falls very short of my reality and experience from my hometown.

Quentin—That counter-narrative, you’re really constructing it. You mention some of your influences from Walker Evans to the Pictures Generation or New Topographics, which is in a way an American history of photography. I have the feeling that you’re also very close to some of the debates that took place around realism in Germany in the 20s through the 50s, around the Frankfurt School with Theodor Adorno, Walter Benjamin, and Siegfried Kracauer.

LaToya—Yes, I would definitely agree. Adorno’s framework was really influential for me. I became fascinated with him during my time at the Whitney Independent Study Program. We talked a lot about Adorno’s seminal essays and the understanding that the artist shouldn’t play a subordinate role to the culture industry. That resonated with me because I was watching my hometown be rebranded as a “new frontier” in 2011. Again, I am borrowing from that history but also looking at current events—the current situation, the current economy. Pittsburgh has had to reinvent itself from its industrial past, under these new notions of what someone like Richard Florida calls the “creative class.” But coming into this post-industrial landscape actually misses massive populations of working class people that have been suffering from environmental trauma and pollution in addition to not having access to real things. Being able to move from that micro to the macro level of politics, economy, and history becomes a driving force for me. The way I understand it is through the Frankfurt School theorists and the fact that they really did question it. Kracauer seems to often be, not cynical or pessimistic, but untrusting of the way these things were being used or justified.

Quentin—Going to the book, is it the main way to construct that narrative for you?

LaToya—When I set out to make the body of work—which took 12 years—I knew it was going to be a book because it had to be a book. That would be my freedom. This goes back to someone like Walker Evans, who was also unapologetic about constructing his own type of images, his own narrative and story and writing, challenging what was happening in mainstream magazines. It was the same case for me. Whether that was challenging our ideas of family albums or even questioning what I saw in the history of photographic exhibitions at MoMA.

Quentin—In the book, you also add text. Is it a way of admitting the fact that photographs cannot tell everything? There are limits to photos?

LaToya—I don’t think that images are purely to be consumed and enjoyed as beautiful objects. There is a responsibility to the image-maker, especially when dealing with social reality or political climates, to ground it in something that has a language and a syntax around it —understanding that you don’t want images that cater to being collected. I’m concerned about the framework and the context, but still backing away from it enough to allow a viewer to project their own meaning and understanding onto it.

Quentin—There is one text that I really love next to the image Mom and Me in the Phase: “We are not in Manet’s A Bar at the Folies Bergère.” Is that a way to say that you don’t want your images to be seen first and foremost as works of art? Or to be read through that prism?

LaToya—Well, I very much see my work as art. Again, going back to this idea of conceptual documentary art, I’m nodding to the fact that I can go back and look at that painting and it never gets lost on me the way that historians have discussed it—looking at the woman’s placement. This woman’s place in society is an overarching feeling that I’m always given when I approach that painting. I’m nodding to it, celebrating it, and embracing it, but I’m also cautioning the viewer, trying to bring them back into my emotional, mental space and the relationship between my mother and myself. So you can look at it as pure art in relationship to painting, but there’s a personal story woven into it.

Do you see a difference between a photographer and an artist? I’ll just say one personal tidbit. When I’m in France, they perceive me as an artist. Then when I’m here in the U.S., I’m always written about as a photographer. I’m always fighting here in the U.S. to be understood as a visual artist. I was wondering from your expertise and the fact that you used those two words interchangeably, what does that mean to you? The nuances of a photographer or an artist—what’s the distinction?

Quentin—It’s true that I use these two words, because sometimes it’s difficult to know how an artist wants to be called. I would say that I usually use the term “artist” or “artist using photography,” but it’s true that I would say that you can use both. For example, I remember that when Hilla Becher would be called an artist, she would often correct people and say, “No, no I’m a photographer!” In a way, sometimes the same thing goes with Jeff Wall, who often likes being called a photographer even if his art or his images are often seen and integrated into the larger realm of art. It really depends, so I’d use artist as a generic term. But some artists want to be called photographers instead, which I can perfectly understand.

LaToya—Do you see the way I’m working as art or photography? The funny thing is I went to Syracuse [University] and got a degree in “Art Photography.”

Quentin—I see your work probably more as art than photography; but I know you see yourself as a conceptual documentary photographer—or conceptual documentary artist. It’s really putting words on practices and talking about definitions and how people like to define themselves. For me it isn’t the most important thing. I usually use such generic terms as “artist,” but it’s true that sometimes people like to be related to that history of photography, they feel a very specific tradition that is very distant from the art tradition. Whereas others stay very close to the art tradition and are openly influenced by many other art forms, from film to painting—and also in return influencing all these art forms. For me it’s all part of that same world.

Photography at MoMA: 1960 to Now is now available at retailers. The next volume, Photography at MoMA: 1920 to 1960 will come out this fall. Photography at MoMA: 1840 to 1920, the final volume, will be available in the fall of 2017. Published by Aperture, The Notion Of Family by LaToya Ruby Frazier is available now.