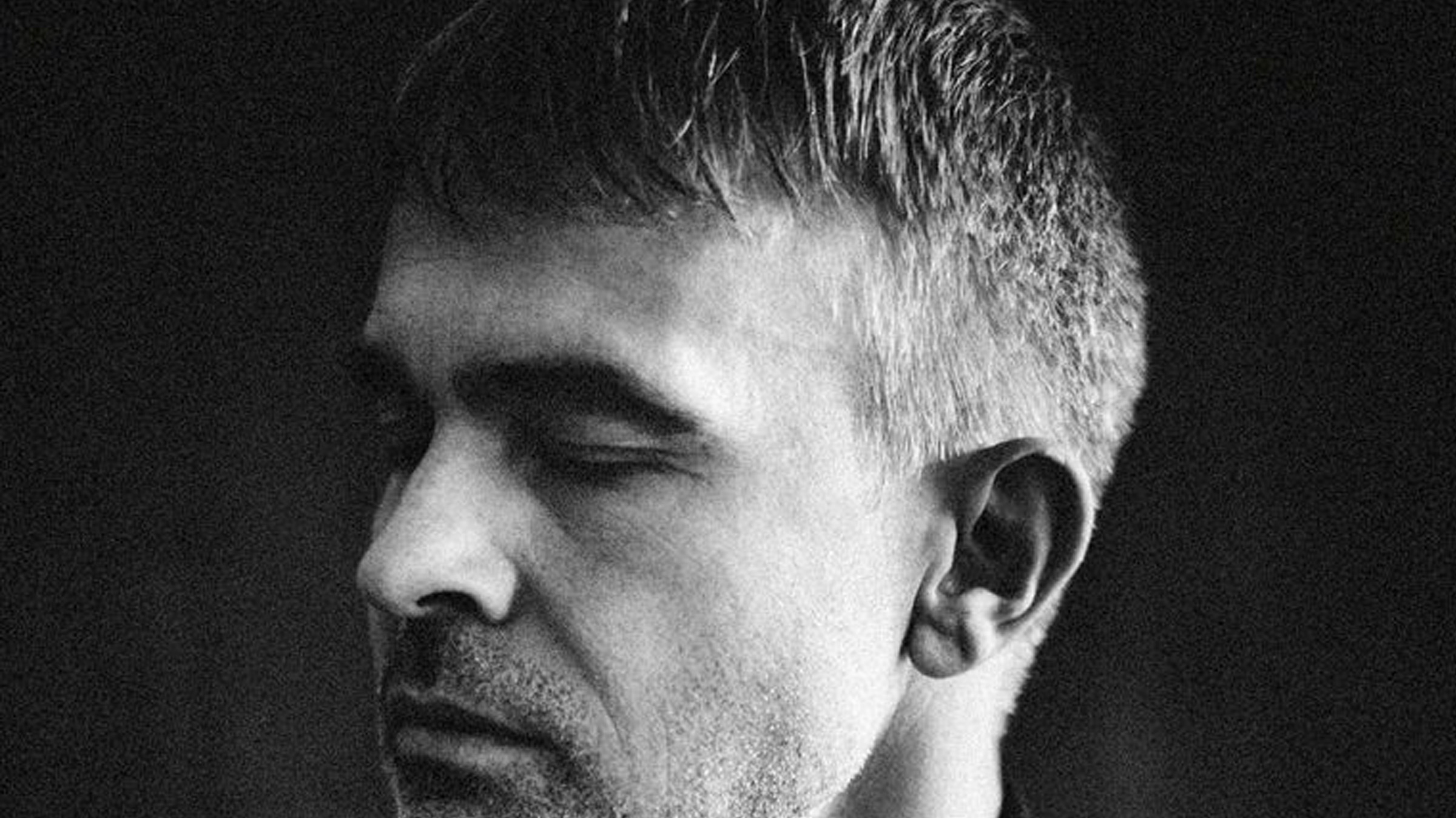

Back in the 90s in Belgium, a group of like-minded young friends were taking their first tentative steps in the fashion world. Among them was the designer Raf Simons, the make up artist Peter Philips, and the stylist (and guest editor of this issue ofDocument) Olivier Rizzo, as well as Willy Vanderperre who, luckily for them—and also for us—was the guy holding the camera. Fifteen years and countless magazine editorials and ad campaigns later, Vanderperre has relinquished his position behind the lens to write and direct a short film, Naked Heartland. But as Alix Browne discovers, after all this time the photographer has stayed true to his vision—and his friends.

Willy Vanderperre—You are so old school recording this. In my head, I see you with a little tape recorder. [Laughs].

Alix Browne—It doesn’t have an actual tape; it’s digital, but yes. You know the last time I used a tape recorder was for a group interview with Larry Clark. I think Bruce Weber was there, and Gus Van Sant, and we arranged this big conversation over dinner at Bar Pitti to talk about the reissue of [Larry’s book] Tulsa. The tape recorder died in the middle of it and nobody noticed it, including me. That was really bad.

Willy—You were all so fascinated by the conversation.

Alix—Yes, and we botched the whole thing.

Willy—That must have been around the same time that we met in New York, as well.

Alix—Exactly. It was back in the day when none of us really knew what we were doing, even though at the time we were so sure that we did. [Laughs].

Willy—Oh yes, we were very serious about it.

Above The Fold

A Whole New World for Janette Beckman

Art for Tomorrow: Istanbul’74 Crafts Postcards for Project Lift

Wearing Wanderlust: Waris Ahluwalia x The Kooples

Falls the Shadow: Maria Grazia Chiuri Designs for Works & Process

Alix—Do you have that feeling when you look back at the photos you took when you were starting out in the late 90s? We were so naïve and idealistic in a way.

Willy—Yes, but that is the beauty of it. You did things for your own purpose—for yourself. And then all of a sudden you thought: “Maybe I should do something more with this.” So you reached out to people who were like-minded. The set-up was so spontaneous. No one was thinking about their career. We just wanted to do stuff.

Alix—That is what I think is very admirable about the way that you, and Olivier, and Raf, and Peter all came up together—as a team in a way. You all have your own careers and are successful independent of one another, but to me it’s amazing how you have all really stuck together all these years.

Willy—There is something to be said about that. At the beginning we were a team without really even knowing it. We were in the same story, just through different mediums.

“It’s a new medium, so in a way it’s like starting from the beginning again. But it’s really in your guts, the story you want to tell the first time, and I think it stays with you.” – Willy Vanderperre

Alix—Let’s talk about the short film you made, Naked Heartland. What makes this one different from other films you’ve done?

Willy—The other films are all fashion or music related, linked to a house or to a band. This one is a personal, long-term project. I wrote it over several years, and the music was composed especially for it by Belgian band Amenra. Certain things really caught my attention, like the Breivik massacre in Norway [in 2011]. This guy goes on an island and kills all of these innocent people, and at the end of the day he is famous and you will never hear what those kids were thinking or doing.

Alix—In your film we meet a handful of kids, and then something terrible happens to them, but it’s not clear what exactly.

Willy—Violence always comes as a surprise. It just happens. It’s only after you trace it back that you start to make some sense of it. It’s almost gratuit–. I don’t know how you say it.

Alix—Gratuitous.

Willy—It’s true, there is never an explanation. And for me that was very important to convey. In July, it was the fourth anniversary of the Breivik attack. The next day was the fourth anniversary of Amy Winehouse’s death, and there was so much commotion over that. Of course she was a big talent and very inspirational. But maybe one of those kids in Norway would have become just as important. We will never know. It was a bunch of young people at summer camp, maybe exploring their first sexual experience, maybe saying I love you to someone, or holding each other, maybe having an argument—who knows? But at that time there was something really poignant happening in their lives, and we’ve already forgotten about it. There is no identity for those kids. I tried not to be too literal in the film. I tried to describe it more like a poem.

Alix—You say that violence is always unexpected, but you definitely create a sense of foreboding in the film, short as it is. There is a lot of pent-up energy. Everyone is closed off from the world and one another. The curtains are always pulled over the windows. It’s a claustrophobic and seemingly volatile situation.

Willy—Completely. You have this whole new generation and they are living through their self-created microcosms on Facebook, on Instagram, and that is the way they communicate. Even in our generation, people have a sense that they are connecting to a larger world, but in fact they just isolate themselves more and more. That is why we decided to make the rooms in the film very small, very tight, everything closed. So yes, claustrophobia. But at the end of the day they, we, all want to be loved; they all want to belong to someone.

Alix—I am curious about the boy in the film who turns on the disco light in his room. He lies down on the bed and the lights are flashing around him like he’s in a club, but he’s all alone.

Willy—It’s so funny that you mentioned that one. When Olivier was a kid, he would be in his room listening to his favorite radio show, and he would turn on these lights that were a present from his grandfather, I think for his 12th birthday. So he’d listen to the music in his room and put the lights on and create his own private club. In the film it’s almost like a little homage.

Alix—The way you tell it seems very sweet, but in the film, the scene seems quite sad.

Willy—It is a violent image and the scene is broken up by these bully videos we made with a handheld camera. The way those videos are posted on the internet. The music is very hard and loud. There is repressed anger in that boy. He’s the kid that suffers the most in the film.

Alix—Having known you for so long and being familiar with your obsessions and the references that have woven their way through your work, and Olivier’s work, and Raf’s work, this film struck me almost as a rewind of the past 15 years. There is such continuity there. All of the things that have been percolating in your creative development are present in a very beautiful and formal way.

Willy—I can only take that as a big compliment.

Alix—I remember trying to convince you to put your work out there early on, but you were always very measured and didn’t want to do too much too soon. You’ve always been consistent that way and very loyal, not only to your friends and your people, but also to your ideas, to your world view. I think this film is a very good illustration of that. You’ve always somehow known what mattered to you.

Willy—It was very important that this film be in my native tongue[Flemish]. It’s a new medium, so in a way it’s like starting from the beginning again. But it’s really in your guts, the story you want to tell the first time, and I think it stays with you.

Alix—The film is constructed almost like a series of portraits, and you could literally pull one still from each scene and make a print story from it.

Willy—It’s true. When I was color-grading, the colorist said to me, “Wait, you’re doing a picture.” But of course, I’m a photographer. In that sense it was very nice to work with Nicolas Karakatsanis, who is in my opinion one of the most talented directors of photography around. He did Bullhead, the amazing Flemish movie by Michaël Roskam, and he did The Drop, which starred James Gandolfini. It was nice to work together and construct the images. We talked a lot about light, about composition. But like I say, also being a photographer, I like to see a good constructed image. But not only that. Like you say, the film is a portrait of kids. Like an image, we tried to explain, in one image, who they are and where they come from.

Alix—Was it difficult for you not to be behind the camera?

Willy—Not at all. Of course I was sitting right next to my DP, but I love teamwork. Nicolas is very picky in what he does. He’s very concerned about his image, and I always praise that. When I started writing four years ago there were three people that I really wanted to be involved: Nicolas and the lead girl, this young Flemish actress, Line Pillet, who is absolutely mindblowing; her dedication is impressive. And Gilles van Hecke, an amazing actor, raw in his emotions. To complete the cast with Aaron Roggerman, a young up-and-coming actor, was amazing. So no, it was not so difficult. It was even nice not to be behind the camera and to hand it over to someone else. Editing was the most difficult part.

Alix—It always comes down to the edit, doesn’t it? Which brings me to the story you shot for this issue of Document. It’s 100 pages?

Willy—100 plus, yeah.

Alix—Is that the longest story you’ve ever done? And is it, in fact, one continuous story?

Willy—We divided it up. It contains a lot of things from our roots that are still relevant to what we do now. It’s mixed up. It’s very autobiographical. It’s very Olivier. And it’s very me as well.

Naked Heartland premieres at film festivals this season. Follow the film at nakedheartland.com.