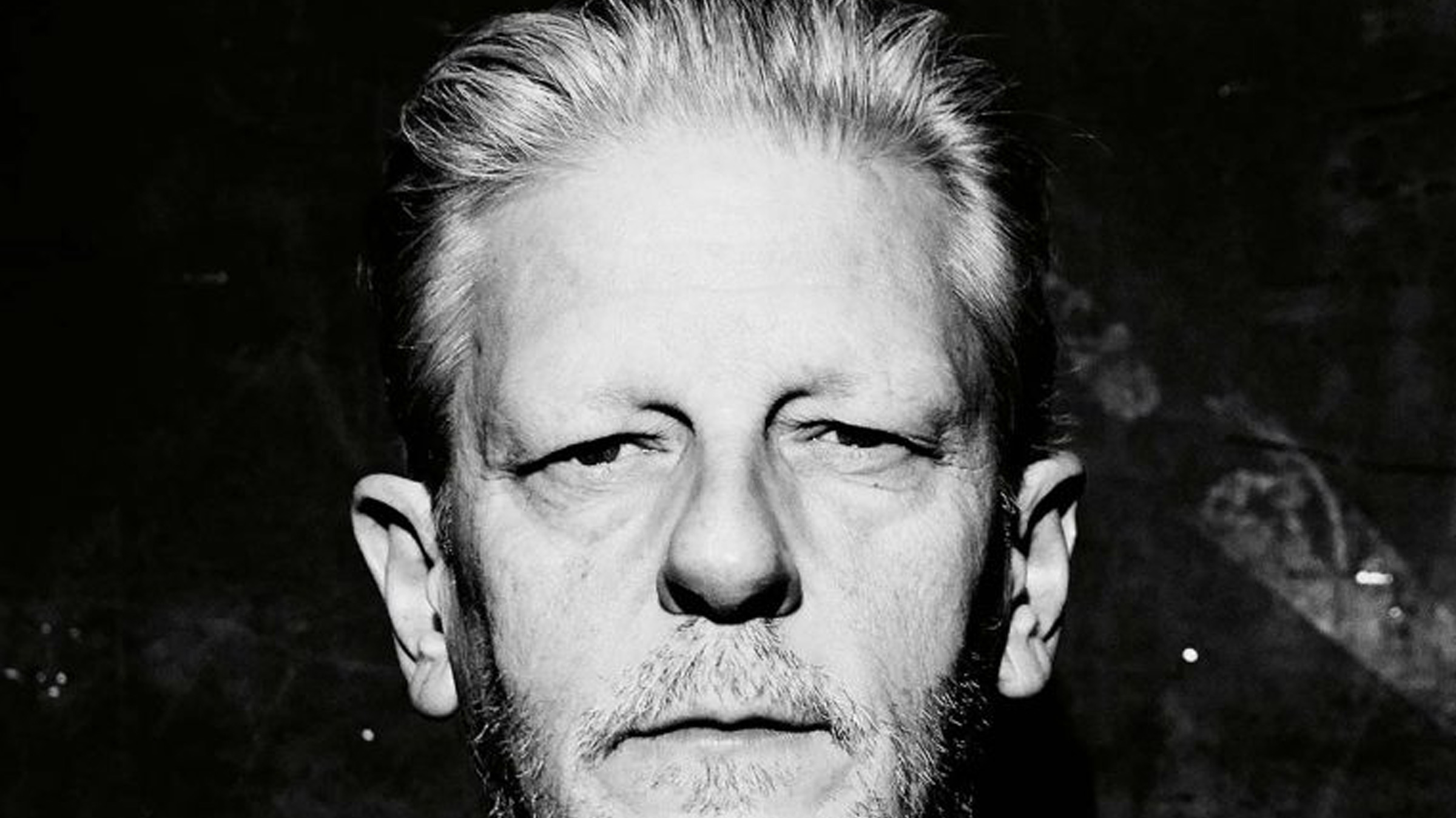

Pushing the boundaries of art is not a new thing for Belgian artist Jan Fabre. He used his own blood for drawings in his 1978 solo performance My body, my blood, my landscape. When the former Queen of Belgium commissioned Fabre to do a performance, he came up with Heaven of Delight, covering the entire ceiling of the Royal Palace in Brussels with green scarab beetles. Fabre also shaped intricate and delicate sculptures of Carrara marble that were on view in Venice a few years ago.

Making art wasn’t enough; he also founded and runs the theater company Troubleyn, which just premiered Mount Olympus, a 24-hour-long piece that played Berlin and Amsterdam last summer. It was hailed a success, garnering critical acclaim and standing ovations, and will travel to Rome and Buenos Aires. I spoke to Fabre during the final days of his most recent retrospective, located in his hometown at the Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst Antwerpen, where we discussed his most recent ground-breaking theater work, and what the passionate and uber-energetic master is cooking up in the near future.

Above The Fold

Toasting the New Edition of Document

A Weekend in Berlin

Distortion of the Everyday at Faustine Steinmetz

Wilfried Lantoine Takes His Collection to the Dancefloor

Tim Goossens—Hi Jan, how are you? I’m in your hometown, Antwerp, for two days. How and where are you?

Jan Fabre—I’m actually in Tuscany, 30 minutes away from Siena, in nature. I’m preparing the solo exhibition knight of the night in Firenze at Galleria Il Ponte and another solo exhibition at Magazzino d’Arte Moderna in Rome, The Years of the Hour Blue.

Tim—I want to start by asking you how are you feeling about the first two venues for the amazing Mount Olympus performances.

Jan—The reaction from the 24-hour play are amazingly positive. We had, I think, a 40-minute standing ovation in Berlin and in Amsterdam something like a 30-minute standing ovation. The reactions were amazingly positive.

Tim—How is a premiere of a very ambitious new piece for you? Do you feel empty at all afterwards?

Jan—I have a little a bit the blues. You work day in and day out from 11 until about 2 or 3 am for 12 months and, of course, running the piece, doing the light, sound, and simultaneously making notations for 24 hours is quite intense, physically and mentally. So it was a double feeling because we, the cast and crew, were tired but at the same time very glad and happy. The success was so unpredictable; nobody expected this. The reaction in the space was almost like an extreme pop concert. I never saw this happening in thirty years working in the theater field. Can you believe most of the people stayed awake for 24 hours?! As the time passes during the performance, the emotional impact becomes greater and more intense for the public. Of course for the actors and the dancers it’s a fantastic feeling to get such a good reaction. I’m still recuperating a little bit, even four weeks after the last performance in Amsterdam. My biological rhythm is completely fucked up.

Tim—How did it start, was it through Troubleyn? I know there was a lot of improvisation, but I’m sure a lot of it was structured as well.

Jan—The first meetings for the Mount Olympus project started six years ago with my production team. Three years ago it became more intense working closely with the Belgian writer Jeroen Olyslaegers, Belgian composer Dag Taeldeman, with my 30-year-long collaborator, dramaturge Maria Martens, and the theater scientist Hans-Thies Lehmann. The next step were the auditions two years ago. In eight different cities in Europe, I saw more than 1,500 young actors and dancers. I selected 20 of them, and they were invited to work with the company and to do a final audition in my own space, the Troubleyn Laboratorium in Antwerp. At the end, six were accepted by the company. The cast [is made up of] the best actors and dancers I have worked with in the last 30 years. They are four different generations—between 65 and 20 years old. I invited cult actors such as Els Deceukelier and Marc Moon Van Overmeir back to the company. I also invited very talented and fantastic performers like Renée Copraij, Ivana Jozic, Annabelle Chambon, and Cédric Charron back again to the company. The working process lasted 12 months with a group of 27 performers. I had some co-producers in advance who guaranteed the budgets, for example the Foreign Affairs festival in Berlin, where I did the premiere; the Julidans festival in Amsterdam; and Romaeuropa Festival, where we will perform in October.

Tim—So do you think there was this need, then? Something where people can feel more immersed? Even though we are immersed all the time with things like phones, but we’re not feeling it.

Jan—One of the basic starting points of the creation was the research about catharsis, and what it means today in our society—in a social, political, and philosophical way. Today, for me, the magic of theater is still bringing people together into one space that creates a here-and-now celebration of life. When the performer and the public immerse together, they exchange and share a deep sense of physical and mental state. The public experiences and shares the performers’ tiredness, their sweat, their smell, their tears. They start mentally and physically feeling what the performers go through. It’s unique in our society today—a society that is so driven by speed and technology—to make a personal decision to give your private time and surrender 24 hours to a piece of theater. That by itself is already a political choice.

Tim—This is such a huge production, this is you leading a team. How does that contradict or help you with your other visual work? How did you take that step from becoming a solo artist into the theater? Was it a learning process also?

Jan—Love and passion was the alibi. When I was a young artist, I fell in love with some actresses and dancers. So I started writing and creating for them. Working simultaneously as a writer, visual artist, and theater artist is something I’ve been doing for more than 30 years. I’m a consilience artist; I’m a servant of beauty who always chooses the right medium for the idea I have.

Tim—Yes, but back then…

Jan—It has to do with my personal energy. The going back and forth between theater, writing, and visual arts is something very organic. For example, the last 12 months it happened often that I stopped working with my theater company after midnight, and afterwards I immediately went working alone in my visual-arts studio. My deep insomnia is not accepting the dictatorship of the moon. So at night I’m more concentrated on my writings and drawings, and this gives me a lot of energy for the next day when I’m working with my actors and dancers. Creation makes me happy. I’m like a contemporary mystic; my work is my breathing, my breathing is my work. Art and theater are my savior and shelter.

Tim—Uh huh.

Jan—I feel sometimes a deep connection with this old classical jazz musicians, masters like Duke Ellington and Count Basie. They were always on the road, day and night. They gave performances in the evening, and at night in the hotel rooms they were playing the piano, joined by women and whiskey, having fun and at the same improvising and composing new music. Next day they gave it to their band, and so the music kept on going. It’s a little bit like this in my life—I go on day and night because I love it, I live through it. Of course my office takes care of the right schedule. For example, the exhibition Stigmata. Actions & Performances (1976-2013), which I made together with [curator] Germano Celant for the MAXXI Museum in Rome, was planned especially before the start up of the 12-month working process of Mount Olympus, so during my working process the exhibition could travel worldwide. This spring it opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Antwerp, and in November it will travel to the Netherlands and afterwards it will go to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Lyon, Warsaw, and so on.

Tim—Can we talk a little bit about the upcoming Hermitage exhibition in 2016?

Jan—As in the Louvre in Paris, I’m the first living artist who is invited to make a large-scale exhibition in the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg. Throughout 15 spaces in the Winter Palace there will be a dialogue between the Flemish classical masters like Rubens, van Dyck, etc., and my work. Together with the Russian curator Dmitry Ozerkov and Barbara De Coninck, we’re selecting works from the 70s until now.

I’m also especially creating some new series of drawings and the coming months I will travel regularly to Carrara, Italy to work on new marble pieces for the exhibition. In the recently renovated—by Rem Koolhaas—general staff building, I will also create some new installations and films. The exhibition is opening September 2016 and I’ve been preparing it already for three years. Next year we’ll be touring with the Mount Olympus performances as well, but the biggest amount of energy will go to the exhibition in Saint Petersburg.

Tim—Amazing! When I lived in Paris, I remember seeing you at the Palais de Tokyo with Marina Abramović. She’s very much thinking about her legacy and creating her institute. Do you ever think about that already?

Jan—Yes, it’s something my collaborators are working on. The first step will be in 2016; the Troubleyn Laboratorium building will become a foundation for my theater work. The city of Antwerp and the University of Antwerp will keep the building as it is, also taking care of all the permanent works created by artists-friends and colleagues. For example, Marina Abramović made a permanent work in the kitchen; Luc Tuymans made a fresco on the ceiling of the rehearsal space; Michaël Borremans painted two works in the theater space, in the main hall of the Laboratory; Bob Wilson created a sort of umbilical cord connecting my Laboratory with the Watermill Center, his own Laboratory. In the future, this Troubleyn Foundation will also be the place where all my theater drawings, writings, models, photographs, and films will be archived and preserved for future generations. There is a group of Belgian collectors preparing together with Barbara De Coninck, director of my visual arts studio and foundation, Angelos. To safeguard that, a body of my work will be kept in Belgium. Because the last years so much was sold to New Zealand, Japan, Australia…work which might never find its way back to Belgium.

Tim—I, myself, grew up with your art in my life, public works such as The Man Who Measures the Clouds on top of the S.M.A.K. Museum, and the scarabée sculpture in the city of Leuven, which I saw every day and every night while in college; and the epic ceiling you created for the Royal Palace. It all inspired me as a young art historian. I wanted to ask you about the young generation—do you feel like you have a mission to nurture them and give them platforms? Like you do with the actors and dancers?

Jan—I stopped all my teaching in visual arts academies more than 20 years ago. I only teach young artists in my theater Laboratorium and my visual arts studio on a more profound and very intense way. So to say, day and night and not in an academic master-pupil way, but much more in the way of sharing, exchanging, and experimenting together. The Troubleyn Company regularly supports young artists by giving small budgets and space to research and perform. I think it’s extremely important to pass on fire to a new generation, such as I got fire from artists from a past generation. Artists have to be humble and need a kind of Promethean generosity.

Tim—Your studio is super organized; you’ve definitely found the right group of people to do that for you. Not every artist is capable of letting go of control.

Jan—I’m very proud of my team. Some of these people work together with me for 30 years, 20 years, and 10 years. I have two organizations: one is for my theater work, the organization Troubleyn (the maiden name of my mother; in old Flemish it means “staying faithful”); the other one is for my visual arts, that organization is called Angelos (meaning messenger and angel). They are a wonderful team. They are not focused on status or success, and until today they are still very critical to me. They are partners in crime and companions on the road. Truthful warriors of beauty.

Tim—So I’m in Antwerp right now, and I know you established everything here. Do you feel like a European artist, now that we’re so international? Or do you think there is still such a thing as a Belgian artist?

Jan—I don’t suffer from this disease called “international-itis.” I’m a very local and provincial artist. I think I’m a very Belgian artist by roots. It goes back to my mother and my father. My father came from a poor Flemish communist background. My mother was from a rich French-speaking bourgeois Catholic background. Out of this marriage I became very Belgian, in a sense. My father raised me with Flemish classical painting and my mother with French literature. What you often see in my works: a consilience of language and image. At the same time my real nation is imagination. My visual arts studio is my country. I’m the king and my works are the constitution.

Tim—Thirty years ago did people think it was weird to do both the visual and the theater? I feel a lot of young artists that I know, let’s say in New York or South America, people even today still advise them to choose one or the other.

Jan—Yes, but at the same time there’s a new generation of artists and curators who think in a different way. Who see the spiritual value of the idea of consilience. When I started out 35 years ago that was not the case; everything was more divided in disciplines. As a young writer and director I was told to stay away from actors and dancers, because I was a visual artist. When I started out I was found suspicious by art and theater professionals, because I took the liberty and the freedom to not box myself inside the system. That made me, in the long run, spiritually very rich and very free. I’m a very good escape artist! I’m the Houdini of the visual arts! [Laughs]

Tim—What about the use of new technology? I know you want to be an artist of your time. When you do the marble, for example, do you use high tech ways of cutting or is it very traditional?

Jan—I believe in the idea of tradition—great avant-garde work is always rooted in tradition. I’m an artist who still believes in the idea of craftsmanship, the physical, and erotic involvement in the material. Everything is made manually. I believe in time—the “brain works.” I’m making in Carrara, marble that deals with the idea of time and memory. The registration of the time of making it—you see in the work a score of time that dictates the spectator to take time to look at it. I go regularly to Carrara to check everything and to work with the craftsmen. In my own studio in Antwerp, I still do a lot manually myself. I’m an old-fashioned tinkerer. This gives me a great pleasure. I have four assistants. I’m involved in almost every step of the working process, and every night I’m still busy with my hands. I still write manually because I don’t use computers. I make drawings every night. I often make small maquettes. I love this the idea of arts and crafts, the pleasure of feeling something in your fingers. My body is also my instrument. Like my work I’m very tactile.

Tim—And super energetic! The idea of going to your studio at 1 am and then working. There has to be a deep need—otherwise you wouldn’t have the energy.

Jan—Just last night I was working at this table until 6 am; I think I just slept for two or three hours. I was up for over 24 hours working on a new text that I’m writing for the French actress Isabelle Huppert, for a new solo theater piece that I will stage.

Jan Fabre’s exhibition knight of the night shows until 18 December 2015 at Galleria il Ponte, via di Mezzo 42/b, Florence. For tour dates and information about Mount Olympus visit mountolympus.be.