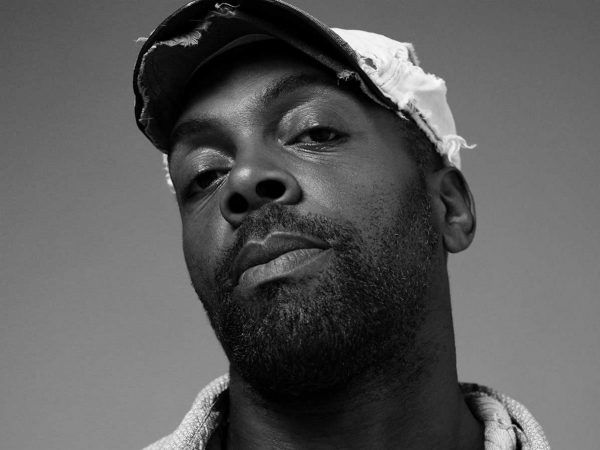

While working as a carpenter at a theater in Kentucky, Boyd Holbrook was scouted as a model and quickly found himself working in Europe and in front of many of the most influential photographers’ cameras. But acting was always his goal, and after he submitted a screenplay to Gus Van Sant, the director was so impressed that he gave Holbrook a role in Milk, which led to parts in The Big C, and Gone Girl. When Dior Homme creative director Kris Van Assche needed to create a “cinematic moment” for the label’s Fall 2015 campaign, he and photographer Willy Vanderperre tapped the model-cum-actor for the starring role. From a set in New Orleans, Holbrook and Van Assche talk about their first encounter over a decade ago, where they are now, and what film means to them.

Kris Van Assche—We met over ten years ago when you—whether you wanted to be or not—were a model. Now for almost nine years, I’ve been at the helm of Dior Homme and we meet again but in a totally different manner: you being an actor, and me needing an actor much more than a model. So it’s funny how we both grew and ended up working together once again.

Above The Fold

Surf League by Thom Browne

Andre Walker’s Collection 30 Years in the Making

New Perspectives on an American Classic

The New Helmut

Boyd Holbrook—I also find it funny that the first time I got the opportunity to go to Paris or Europe in general was for Dior Homme. So it really came back around. I had just dropped out of college and was working for UPS unloading planes from midnight to eight in the morning. I then started working at a department store where I met [the actor] Michael Shannon—I asked him how he got into acting. He told me to come to a theatre company, where I started as a carpenter. Some girl asked to take a photo of me. I asked what for, she said modeling. I didn’t even really know what that meant at the time—that was how green and naïve I was. I ended up working with you a long time ago. I think we were both kind of finding our way in life. It was obviously a really overwhelming experience for me to go to Paris for the first time; I was really jumping into the deep end. Growing up I wrote a lot, and I discovered film at 16. I was like, “I don’t know what the fuck that is, but I want to do that!” There’s a film called Slam, about a spoken-word poet growing up in the ghettos of Washington, D.C. That was the film where I said, “Okay, this is what I want to do. That is life right there, that’s expression, I want that.”

Kris—I remember being young and seeing Jane Campion’s The Piano, and aesthetically it blew me over. I’ve watched that movie about 25 times. This was the VHS period, so I think I actually destroyed the movie. I can totally love a movie for a season, because it gives me an energy or character or whatever, then totally love another one the next season. Bullhead, the movie by Michaël Roskam with Matthias Schoenaerts, I totally love it. It’s Belgian and it has a very, very Belgian feel about it. It felt awkwardly familiar, and it’s both totally extravagant and romantic. Mommy by Xavier Dolan felt like an emotional turmoil. I found myself crying when the scenes were funny and laughing when the scenes were sad. You feel guilty smiling when it’s sad. It’s a roller coaster.

“A really good lesson I learned a long time ago is that you don’t become the character, the character becomes the actor—if that doesn’t sound too confusing. Rather than trying to go through it, it just kind of jumps onto you. ”

Boyd—The Avengers is your guilty pleasure! [Laughs].

Kris—Film has always been part of the campaign, and this season we really wanted to take it a step further and really get into the acting—not using a model, but an actor to push the character and storyline further. From day one that really was the idea, so I found you, Boyd. I thought, “This is such a great opportunity to see how both of us are ten years later.” I was excited that you were working on very interesting projects—a lot of interesting stuff was going to come out. It felt like a good match.

Boyd—It’s so nice to hear that said. We had a really great relationship years ago when we met. I admire you for doing your own thing, not following the cookie-cutter path. For me too, I’ve worked extremely hard on my projects. Through modeling I could pay for film school and got into drama school. No one helped me out. I didn’t know anyone in the “business.” I had to put on a play on my own with my own money through the theater school to get an agent. You’ve got to get an agent to get a role, and you can’t get a role if you don’t have an agent! You’ve got to hustle, and that’s just as exciting as making work.

Kris—It was a very interesting process to see how we would go from a catwalk, from a basic idea, and take it all the way into a movie character. This time, not using a model, but a real actor makes it even more interesting, because you add a lot more to the character. Each catwalk show tells a story; for this show the character I had in mind is a boy going to the opera, bringing his girl, putting a flower on his lapel. It’s really interesting to discuss that with Willy [Vanderperre, who directs the film and shoots the campaign]. Once Willy has seen the show, he starts working, pushing this character even further. It gives me another view on my own work through somebody else’s eyes. Willy does tons of research and totally prepares his work. He is the type to do his homework full-on. But on the day of the shoot, he will also let go and go with the energy. So it really was about different elements and different people coming together and that made for the movie.

Boyd—Taking it on a very simple level, film is about a story. The character is living a narrative and with this narrative I, as a person, as Boyd, can enjoy something that is radically alien to me: Paris. I grew up in a place in Appalachia, in Kentucky, where it’s very mountainous and green—the polar opposite of Paris. One isn’t better than the other. They’re different. It’s a beautiful thing being open to that. So in a simple way, through the story I was taking on the awe of seeing Paris for the first time.

Kris—It was fascinating and very distinct from previous things we’ve made. Film is a very different medium than the catwalk shows. Campaign [images] are still, and it’s much more exciting to have movement, to have sound—it adds another dimension to the work. It really enhances the character I have in mind when I work on a show.

Boyd—A really good lesson I learned a long time ago is that you don’t become the character, the character becomes the actor—if that doesn’t sound too confusing. Rather than trying to go through it, it just kind of jumps onto you. It’s not this mystical thing where I disappear and speak to you in a different way, or I can’t remember my past. I’m always going to be me; we have many different personalities inside all of us. We can get angry or can love—we can all be that. It’s like you were talking about in looking through new eyes, seeing your work in different interpretations gives breath, gives life.

Kris—This film really had to be shot in Paris, because it was really part of my story. From day one it was very important, because it had been very important to my collection, which was about tuxedos—very French and elegant. Taking a girl to the opera: it had to be the Palais Garnier in my head. Putting flowers on your lapel: it was a nod to Mr. Dior, who was so much about flowers and women. And me being so romantic about flowers and men. An American in Paris added an extra layer which created this romantic idea. Rather than you taking selfies near the Eiffel Tower or the park—wherever—you took flowers to collect memories of your walk, of your stay in Paris. It had to be Paris. It had to be about this boy thinking about his girl and picking souvenirs.

Boyd—For me, it’s about finding out the story and making it specific: if the story is about love, then it’s not about something else. It gets tighter and tighter. I research the character and the writing and read the script over. It becomes more like an existence: you’re not really trying to put on anything, you inhabit it. It’s manically acquiring as much information as possible, as fast as possible.

I used to work for a sculptor and he would talk about the need to develop your own language. I didn’t know what he meant by that until the last couple of years when it really made sense. It’s more about a shorthand, not a mystical thing; if you talk about a tool—like a hammer—you can just say, “I need that,” and your mind jumps ahead knowing that it’s going to do steps A, B, C, and D. That will take me to another part in the process. You don’t have to sit there and discuss that process with another person. That can only be calibrated or acquired with repetition and time. With your work you’ve done it for so long; it has gotten to a point where it’s free-flowing.

Kris—It’s very important; I’m very much a storyteller. At Dior, it’s even a necessity. I work on four collections a year, which means that some stories overlap, some collections overlap. In order to stay totally focused and in order to be able to go all the way in whatever story I wish to tell, it has to be about a real character. This character needs to lead a life, needs to want certain things, have a job, have a girlfriend, go to the opera for the last season. It can be whatever but there has to be a story, because it keeps me on the right track while I’m working. It also allows for me to work on different stories at the same time.

Boyd—It’s like if you don’t have a story then really you don’t have a structure.

Kris—Without a story it would just be clothes on racks. They do come alive in my mind; they’re real people. What I had in my mind was a character that could embody tradition and formal elegance, but be real and totally contemporary at the same time. When you’re going to do a Dior Homme show—tuxedos and all—it can easily get old fashioned because tradition, in most cases, is about looking to the past. This character would indeed take his girlfriend to the opera, know all about wearing tuxedos and bowties, and know how to put a flower on his lapel. But he would also be really cool. He would not be 20s or 30s; he would be 2016, so he would do that on a bike, or on a skateboard. He would be very much into today. In that way I felt that you could be the man to wear tradition and be perfectly real at the same time. That’s why this film and the choice of you made total sense. That’s why you were so right for the character I had in my mind.

Boyd—Thank you! [Laughs]. When something is in your mind and when you start physicalizing it, it can become something totally different. You take a script: it is really just a blueprint until you take it to location and start getting it on its feet. It can become something different. Things keep evolving, which is always exciting, and things keep popping up when you’re doing it. Did that happen, Kris?

Kris—I didn’t even know what your hair was going to look like until we met the day before. You’re doing all these roles…

Boyd—[When we shot], I had just come off from a film. And while it’s kind of a novelty, I had to keep my hair at a certain length; it became this sort of Sid Vicious style. And I was gaining weight; I had gained 30 pounds! [Laughs]. I remember for the campaign we had pants, and they used the same exact size to take to the [catwalk] show. I remember I tried to put the pants on a month later, and they wouldn’t go above my thighs!

Kris—It was a bit of a drama moment a few hours before the show! [Laughs].

Boyd—It’s cool! I just love being romantic about ideas and thinking about them. I’ll admit why I do things is because it’s always just like a daydream and then turns out to be something different, which is fascinating.