Current and past members of the non-profit artists' bookstore reflect on the beginnings of Printed Matter and it's enduring significance.

“Artists’ books are, like any other medium, a means of conveying art ideas from the artist to the viewer/reader. Unlike most other media they are available to all at a low cost. They are not valuable except for the ideas they contain. They are works themselves, not reproductions of works. Books are the best medium for many artists working today. The material seen on the walls of galleries in many cases cannot be easily understood on the walls but can be more easily read at home under less intimidating conditions.”— Sol LeWitt in Art-Rite, Issue No. 14, Winter 1976/1977.

In the postdiluvian wake of Hurricane Sandy, Printed Matter, the nonprofit alternative space dedicated to artists’ books, teetered on the edge of extinction. Emergency planners closed the tunnels in and out of New York City, shut down all subways, and mandated evacuation of zones closest to the Hudson River, including much of Chelsea. The 225 plus galleries in that neighborhood worked furiously to protect irreplaceable artwork, though nothing could have prepared anyone for the six foot water wall that would flood the streets. Some of the most powerful art world institutions and commercial mega galleries were devastated by the storm, and several non profits sustained terrible losses.

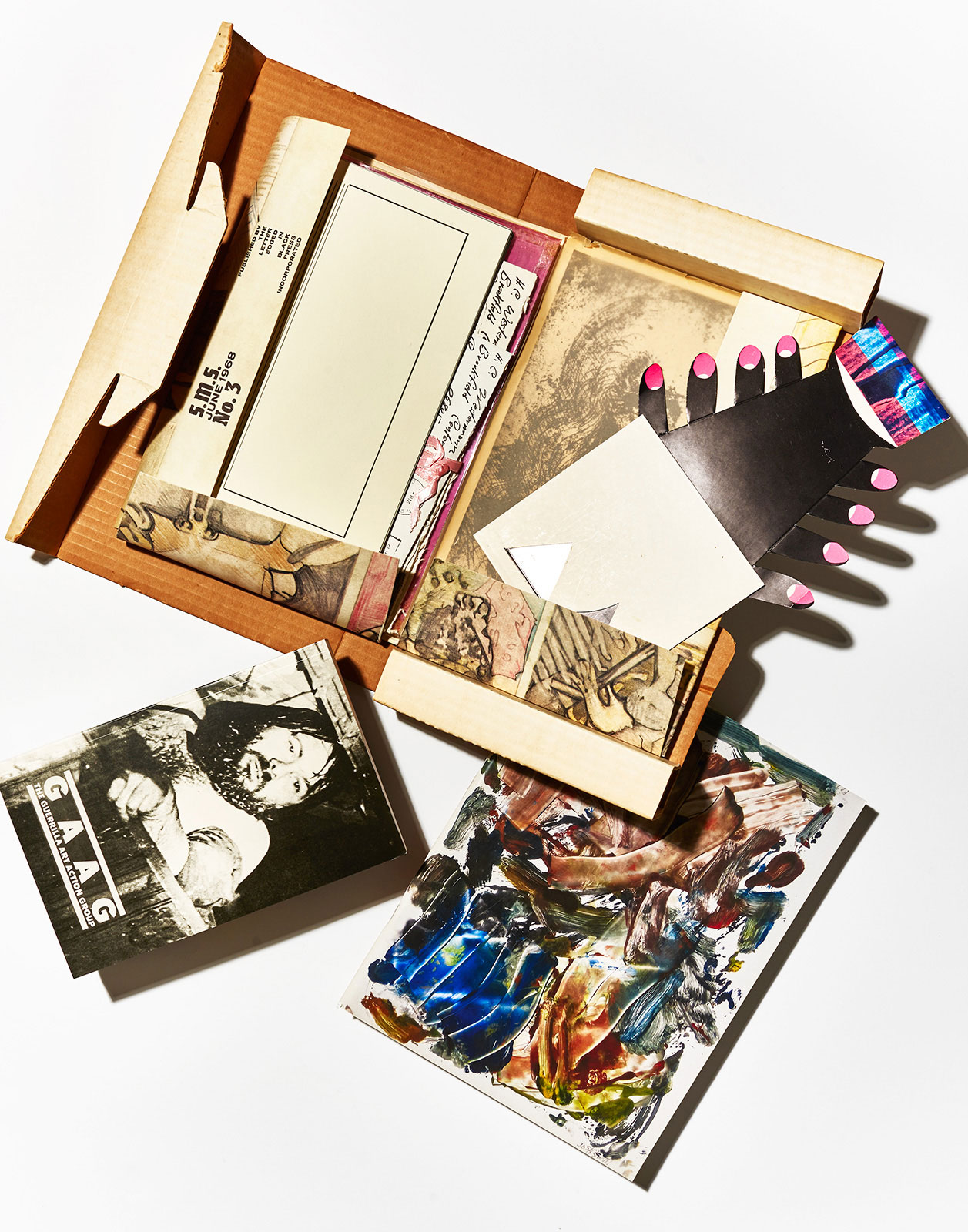

In one night, Printed Matter would lose most of its archive dating back to 1976 and more than 9,000 books of inventory, most of them stored in the basement. As a struggling nonprofit organization, they could not afford insurance so would not be reimbursed for what was lost. In the days that followed the second most costly hurricane in U.S. history, most of lower Manhattan was in a blackout. When the lights came back on, the entire art community knew about Printed Matter’s crisis. Among people who dedicated their lives to art, a flood of support came to the small independent bookstore. Volunteers helped recover what could be spared from the books floating in the water or drenched on the streets, while donations came into the store from around the world.

Printed Matter remains full of the spirit of the 70s conceptual artist and activist, with the utopian ideal of bringing art to everyone and the belief that art can ignite political change. It is one of the places in art that still really matters. And nearly four decades after it began, Printed Matter may now be having its greatest impact on a young generation of artists. But perhaps the greatest mystery is how Printed Matter got started at all.

The first iteration of Printed Matter was brought together in less than one year. The founding members moved their way through spaces in the rapidly gentrifying areas of Tribeca, SoHo and then finally Chelsea, all the while dealing with rapidly increasing rent, accumulating debt, heated arguments, members quitting, the culture wars of the 80s, and the continually changing business model.

One of the founders, Lucy Lippard, the cultural critic, curator, and public intellectual described the beginning: “My first vivid memory of Printed Matter is sitting in my loft with Sol LeWitt—in front of the coffee table he made me, piled with a mess of books— and he came up with the idea of publishing artists’ books.” But there are other versions:

WALTER ROBINSON (Founding member of Printed Matter, only active in 1976. Co-founder of Art-Rite magazine, painter, critic, writer, and founding member of artnet.com.)—What I remember is that Lucy Lippard came to us, Edit [deAk, the co-founder of Art-Rite and an art writer], and me, with the story that Sol LeWitt’s accountant had suggested he get a tax write off—they had the idea of publishing some artists’ books. It was a hot topic, artists’ books. All the cool artists were doing them.

AA BRONSON (Former Executive Director of Printed Matter, 2004- 2010. Artist, curator, founding member of the art collective General Idea (1967 to 1994), founder of FILE Magazine, founder of Art Metropole, an artists-run center and bookstore.)—We sold Sol Lewitt’s books at Art Metropole [in Toronto], and he was one of the founders of Printed Matter. There were seven founders in total [nine are officially listed, however] and Walter Robinson was one of them. Part of the impetus to start Printed Matter was to have control over the prices their own books were being sold at.

MAX SCHUMANN (Current acting Executive Director of Printed Matter, employee since 1990.)—People have different memories. It all attests to the need at that point for an organization to be formed because of this identifiable activity of artist publishing and the need to represent it.

PAT STEIR (Founding member of Printed Matter, 1976 to Present, painter, artist, and activist.)—I was in Italy in Genoa with Sol [LeWitt, the minimalist artist] in 1975. I asked him if he would back a poetry publishing company for me. He said he would on the condition that we expanded the publishing to include any kind of artist book. Sol’s idea was more inclusive because it included poetry.

MIMI WHEELER (Founding member and first co-director of Printed Matter, 1976, gallery director of American Fine Arts.)—I was with Sol, and we were not interested in poetry; it was always about artists’ books from the beginning. We started to think about creating an artist books bookstore while we were in Amsterdam for Sol’s exhibition Prenten-Prints at the Stedelijk Museum in 1974.

WALTER ROBINSON—Even though Sol was the paternalistic “big daddy”, It was going to be a collective and everyone was going to have one vote. It was sort of like that because Sol was a benevolent tyrant [laughs].

It is no surprise that the idea of starting an artists’ books bookstore may have come to Sol and Mimi while they were in Amsterdam, where at time there was one of the most important—and one of the first—stores dedicated to artists’ books, Other Books and So.

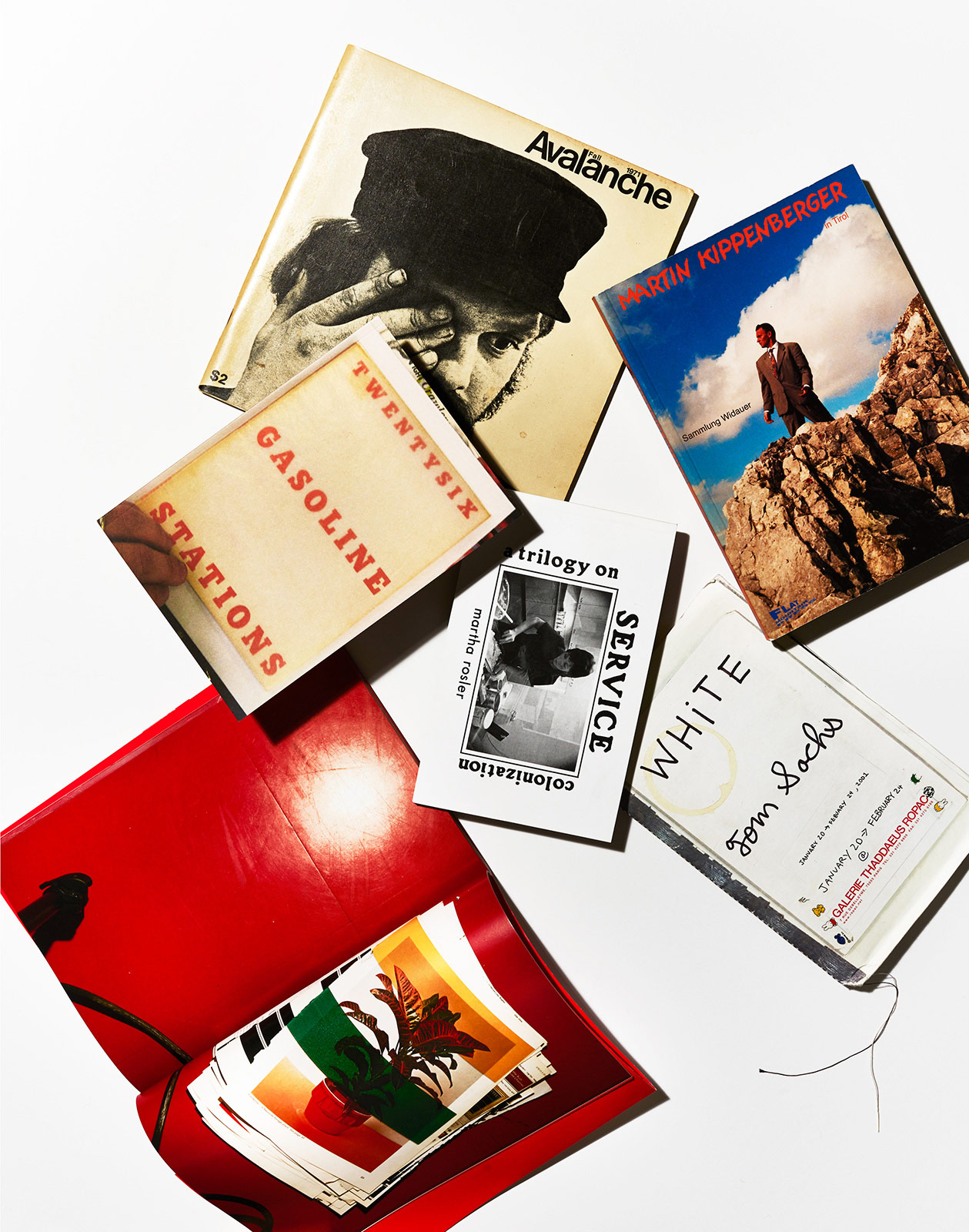

AA BRONSON—The first artists’ books bookstore I am aware of was called Other Books and So, in Amsterdam. Half the bookstore was political, anarchist, and Marxist books, and half artists’ books. They also had exhibitions on the walls that might have looked very much like Printed Matter looks today with tables stacked with books in the middle of the room. Artist publishing was really tied to the idea of resistance, while appearing quite playful.

MARTHA WILSON (Founder of Franklin Furnace, artists’ book maker, performance artist, curator, and writer.)—And at the same time the exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art curated by Kynaston McShine titled simply Information had works of art that were text driven, concept driven. In 1970 when I moved to New York, I was living downtown doing these little publications and took them uptown to the Museum of Modern Art bookstore. I asked, “Will you sell my publications?” The manager of the store said, “Look lady, your publication costs $5, but it is going to cost us $5 to stock it and do the bookkeeping. So the answer is no, we will not sell your artist’s book.” Artists at that time were also doing street work, temporary installations. Barbara Kruger would put up a giant ass poster on the wall overnight or take over storefront windows. The uptown community—except for McShine’s Projects Room—was not paying attention to what the downtown art scene was doing. Printed Matter was actually one of the last organizations in a series of chain-reactions that began very rapidly in the 70s in downtown New York. At the time Tribeca and SoHo were exploding with a burgeoning new art scene.

WALTER ROBINSON—In 1973, I moved to Tribeca and had a loft. In the 70s the whole alternative space movement grew up in opposition to guys who were fucking bureaucrats in the art world, taking government money in the name of artists. The artists objected to that and tried to start their own thing.

PAT STEIR—I wasn’t clear why we needed a board if we were going to make money. Edit invited Robin White, Irena von Zahn, Mimi Wheeler, Walter Robinson, and Lucy Lippard. But everyone has a different memory of it, and I think it is so fabulous to look at all of them. It seems like everyone at the first meetings thought they started it. In a way they all did.

MIMI WHEELER—Alot of people wanted to be co-founders, and the rest of us who were, paid the price [laughs].

In some ways the history of Printed Matter is tied to a background of the need to find affordable real estate. The first order of business was to have meetings with the founding members to find the real estate to open the bookstore. In the very beginning they would meet inside Franklin Furnace, a former sister bookstore that now serves as an archive of art books.

MARTHA WILSON—Franklin Furnace was in a building that was found by the artist and publisher of the artists magazine Avalanche, Willoughby Sharp, who was adamant that the building become the Franklin Street Art Center. It had bookcases in it already, because it had been a ship chambering, I saw it could be a bookstore, but I did not want to get into bed with Willoughby Sharp [laughs]. So I incorporated separately in April of 1976 before Printed Matter. I had the space inside the Franklin Street building and I wanted Printed Matter to move in and do this together. But Willoughby Sharp’s lawyer, Robert Projanksy, came to a meeting we were having and said, “This will never be known as the Printed Matter Building.” Willoughby did not want the building to be associated with an organization he had not founded.

MAX SCHUMANN—There was a press release announcing Printed Matter’s move from Franklin Furnace to 105 Hudson Street. Printed Matter, was called “working group,” it was a cooperative briefly located at Franklin Street. There were weekly meetings— even more than weekly. And the people who were in that group were definitely Mimi Wheeler, Sol LeWitt, Lucy Lippard, and Pat Steir. Even additional people like maybe [the artist and architect] Peter Downsbrough who would later work as an employee of Printed Matter. The meetings were happening every other day as people were hashing out what Printed Matter would be.

ALICE WEINER—I remember [Edit deAk] working at the first Printed Matter at Hudson Street at a time when there were well produced, cutting edge exhibitions. Julian Pretto [who would become a significant art gallerist] was a part of that early time too; he was the real estate broker who arranged the space and later became the first dealer with a pop-up art gallery.

PHIL AARONS (Current Board President of Printed Matter, began his involvement around 2002.)—We had a storefront on Wooster Street, but a beautiful big store front owned by Dia [Art Foundation]. It had been offered to Printed Matter as a store out of the longstanding Printed Matter and Dia relationship. But when I was called in, Printed Matter was having trouble paying the rent to Dia.

Then, as co-founder Lucy Lippard recounted in a lecture at the retrospective, Learn to Read Art: A Surviving History of Printed Matter, “When we moved to Wooster Street, Dia took us under their wing and later kicked us out from under their wing.”

FRIEDRICH PETZEL (Art gallerist, involved in and supporter of Printed Matter since 2002)—They needed a space. We talked about this, and I was really thrilled, because of the history that I experienced with Printed Matter. I thought it was great not to have another contemporary art gallery in Chelsea right next to me, but something that adds to the community. But with having Dia upstairs, I thought Printed Matter aren’t responsible for the rent, I am. They could be my subtenant, and Dia can’t really do much about it.

AA BRONSON—When I came to Printed Matter, it was located at 525 West 22nd Street. 2004 was a very different time. Most people did not walk off Tenth Avenue down the streets to see the galleries. We decided to move to have a more mainstream location. At the same time we began to rethink the organization, which was heading to be a store only for collectors. We wanted to take it back to its grassroots beginning for artists and friends of artists and anybody who might discover the material for the first time.

The second order of business that started immediately upon founding in 1976 was to create an inventory for the store to sell; some books would be published, but the vast majority would come from submissions. The open submission process remains the nerve center of Printed Matter, and being accepted into the store and inventory really means something.

WALTER ROBINSON—Because there were already a lot of artists‘ books—Ed Ruscha had self-published his books in California— Sol [LeWitt] and Carl [Andre] were publishing their books, or their European galleries were publishing books. What we really needed was an artists’ books distributor.

MARTHA WILSON—Franklin Furnace was a museum for hot air [laughs]. We were creating ideas and creating discourse by making artists’ books. We were creating an opportunity for ideas to be exchanged. In June of 1976, we decided to divide the pie. Franklin Furnace would have the right to do exhibitions and archiving, and Printed Matter would have the right to the publication and distribution. So I gave over Franklin Furnace’s entire stock of books to them to sell.

MIMI WHEELER—Sol’s idea was not to publish. I think Lucy wanted to. I was the first employee, along with Irena. We were co-directors and were each paid $250 per week. Irena was a brick, she paid attention to extraordinary detail. She would mail out 1,000 letters at a time. Later on Ingrid Sischy [the former editor-in-chief of Interview] would take on the executive directorship she was just out of Sarah Lawrence College. It made me crazy, but none of us thought of how to run an actual business. Here we were taking any product sent to us, and we had to market and sell it. In those days, you could send books through the mail at a cheaper rate labeled as ‘Printed Matter’. That’s where the name came from.

AA BRONSON—With Seth Siegelaub [the influential gallerist and political activist], the spheres of influences were overlapping and bidirectional. His artists’ books all happened before Printed Matter, in the late 60s, and he really set a precedent. International General was a very important publisher in New York for conceptual artists. Each book was intended to be an exhibition. Printed Matter was always involved with rules—maybe because Sol was a founder. They had special rules, and liked to have everything in writing, because the early group was very unruly. In order to be an artists’ book, the book had to have a certain number of pages and number of copies. The basic idea was that artists can make low-cost editions which could be distributed in a broader audience than in a gallery system.

“Sol’s idea was not to publish. I think Lucy wanted to. I was the first employee, along with Irena. We were co-directors and were each paid $250 per week.”—Mimi Wheeler

PAT STEIR—By the time I approached Sol, I had a background in publishing and as an art director. I was afraid that making art might fail, so publishing poetry would be the perfect backup. Little did I know that poetry does not make anyone money [laughs]!

WALTER ROBINSON—I grant Edit a lot of credit for making things possible, because she was a first generation immigrant who had no fear. She grew up in Hungary where she married another artist, Peter Grass. As teenagers, they escaped across the border in the trunks of two separate cars. She really was, in the 70s, somebody who made things happen.

PAT STEIR—It was a radical notion because we didn’t vote on the books we published. It began at first all word of mouth. Several thousand books came in, but we turned a lot away. Either they were too precious, expensive, handmade, or there weren’t enough copies of them. We only wanted really affordable art; we wanted industrial.

Ironically as Steir recalls, the board never voted on the first submissions, they simply accepted everything that was sent to them to be published. The last order of business for the existence of Printed Matter was the long battle with the IRS to move from being a for profit store to a full blown nonprofit alternative space. Ironic, though, that the same lawyer, Robert Projanksy, who gave Printed Matter the boot from the Franklin Furnace location would be the one to write a letter on their behalf to the IRS.

MAX SCHUMANN—There’s different levels of selection policy in the beginning, and as part of the application for the nonprofit status, there is a strong emphasis on the absolute inclusivity of anything that was identified as an artists’ book. You’ll see different internal debates about what the parameter should be or criteria should be for the selection of books. Eventually it became impossible to include everyone because there was too much out there. ]

PAT STEIR—We realized that we couldn’t support ourselves by selling books unless Sol wanted to send a check every week. Until we went nonprofit, it was really all Sol’s money. We were basically a for profit, or “for no profit” organization. At first [the nonprofit gallery and organization] Artist Space acted as an umbrella organization, so we could apply for nonprofit status. Then there was a “please clarify” letter from the IRS. Ingrid wrote a brilliant proposal and careful response to the IRS. She said nonprofit theaters, such as The Kitchen, sell tickets; and so books are like “a performance for shut-ins”. Her careful rebuttal is what won over the IRS.

PHIL AARONS—For many people, Printed Matter is not known as a nonprofit, it is known as a bookstore. And from that point of view, it has never had as its primary focus the kind of developmental fundraising that foundations have. We really were struggling along and the way it evidenced itself most dramatically was during Hurricane Sandy. It may have in many ways saved us. It was both a trauma and an ultimate blessing. The pressure and the possibility that Printed Matter would not continue was such a powerful signal for the community to support us. People responded with unbelievable generosity, to an institution that they have always loved but never thought they had to support.

ALICE WEINER—When I stepped up to the plate, Printed Matter’s debt was over $90,000—The debt was less when my time was up. The Executive Director was as ‘employee’ of around 12 divergent personalities. I focused on the artists’ book phenomenon and developing new contacts, starting in Europe. The neighbors upstairs from Printed Matter showed me a mass-produced enamel pin that they had gotten on a trip. Pins are all over the place now but then, it was special. I thought this would work for the store: design a pin for Printed Matter with the idea of disseminating the idea of “reading art”. It would be sold, pay for itself, and advertise Printed Matter on people’s clothing. I was busy and asked [the typographic artist] Lawrence Weiner to design the framework of the pin and make the wording on the slogan fluid. That little pin became:

PRINTED MATTER / BOOKS BY ARTISTS / LEARN TO READ ART

AA BRONSON—The original New York Art Book Fair in 2006 was not only for artists’ books, but was for all types of art publishing. The idea was bringing people physically together, where to meet, talk, and exchange ideas. The first year we had 70 exhibitors. We thought if we got 35 exhibitors that would be enough, so we were really thrilled. 12,000 people came the first year—that blew us away. The last one, 35,000 came, and we had 350 exhibitors.

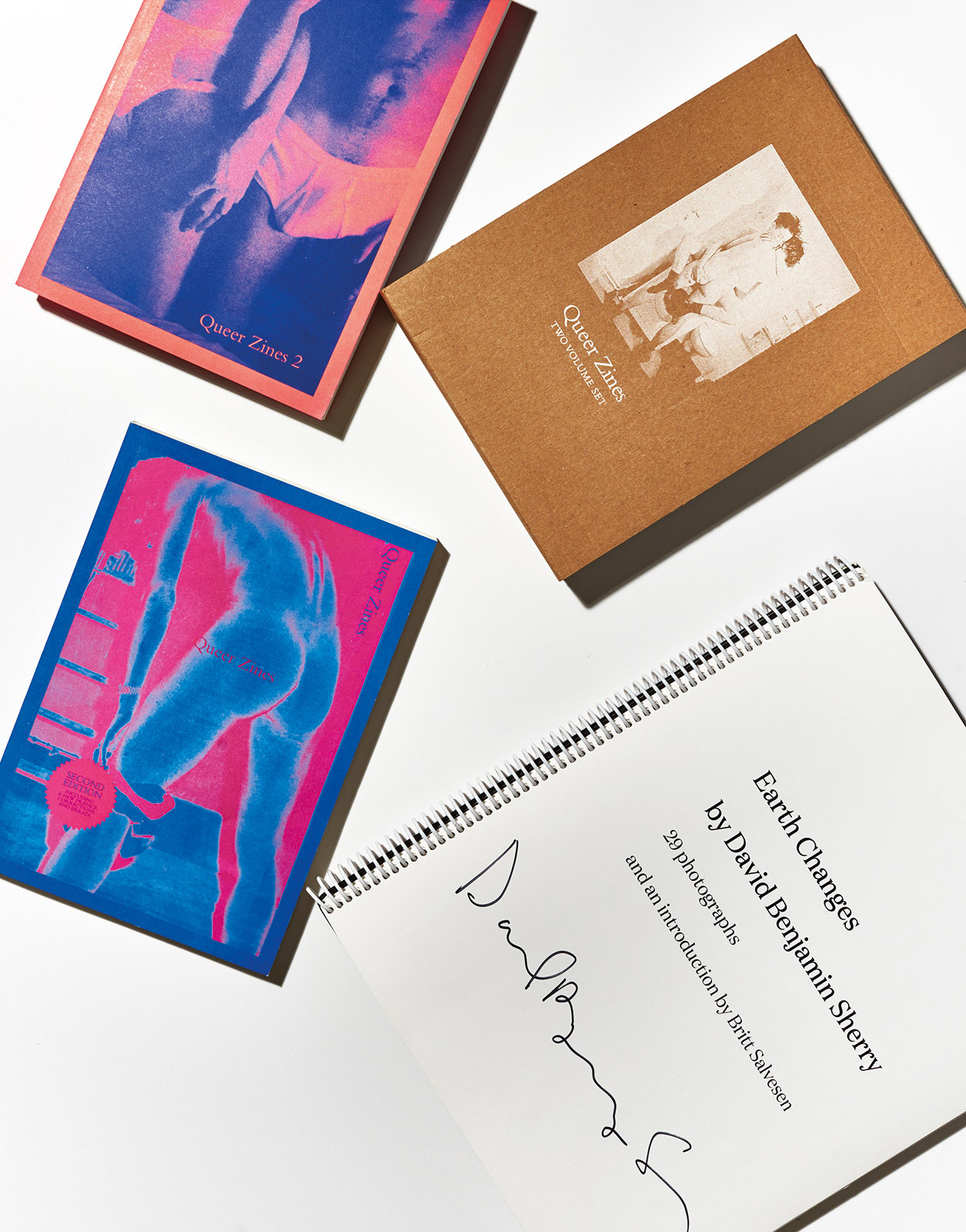

One good example of the kind of things we were able to do through Printed Matter is the queer zine exhibitions. It started in 2008 for the New York Art Book Fair, and we brought together around 70 queer zines publishers and put together our first volume collection of queer zines. Queer zines are intended as a way for certain people who feel like outsiders to get in touch with each other. And they are people that feel outside of gay liberation. The queerzine movement is about people who always considered themselves be one-of-a-kind. In queer zines you can always see the hand of the maker. More than any other publication, that kind of typifies this idea of the renegade artist publishing whatever they want to publish and totally outside of the normal publishing world. In a way, it’s a kind of community building activity.

PHIL AARONS—Printed Matter is moving to a phenomenal new space at 231 11th Avenue at 26th Street into a two-storey space in a historic landmark building: double height with more exhibition space, a reading space, and space for artists and authors to give talks. And in 2016, we will launch our third Art Book Fair in Melbourne, Australia [after Los Angeles and New York.]

AUBA AUERBACH (Artist and board member of Printed Matter)—I found out about Printed Matter from my friend Amy Francis Schmidt when I was a teenager. I sent them a zine which they rejected, but later accepted another one I sent—it was a big deal. My real involvement with Printed Matter began when I designed this pop-up book. I show it to a number of people, one of whom was AA Bronson. He was like, “Yeah we want to make this. Let’s work on this together.” That really launched something because it was such a laborious and difficult process, but a good experience. It led to something that has become a big part of my practices. There is an inherent politics in publishing. I often think about very subtle gender politics in my work and the structure of how I go about publishing; an objective of mine is to make work that is really androgynous.

ALICE WEINER —Politically speaking, I always thought what was Printed Matter’s strongest 60s principle from its founding was that an artist could not be refused submission of her/his artists’ book to the store. For the last several years though, they reserve the right to refuse them. I know it was a lot of trouble to accept books without judgment, but I thought the principal made it worth it.

WALTER ROBINSON—The thing that is interesting about Printed Matter was that there was this idea of being a collective—and we believed in that pretty much.

MAX SCHUMANN—The utopians have a saying: Keep the torch lit and keep the dream alive.

This article first appeared in Document’s Spring/Summer 2015 issue.