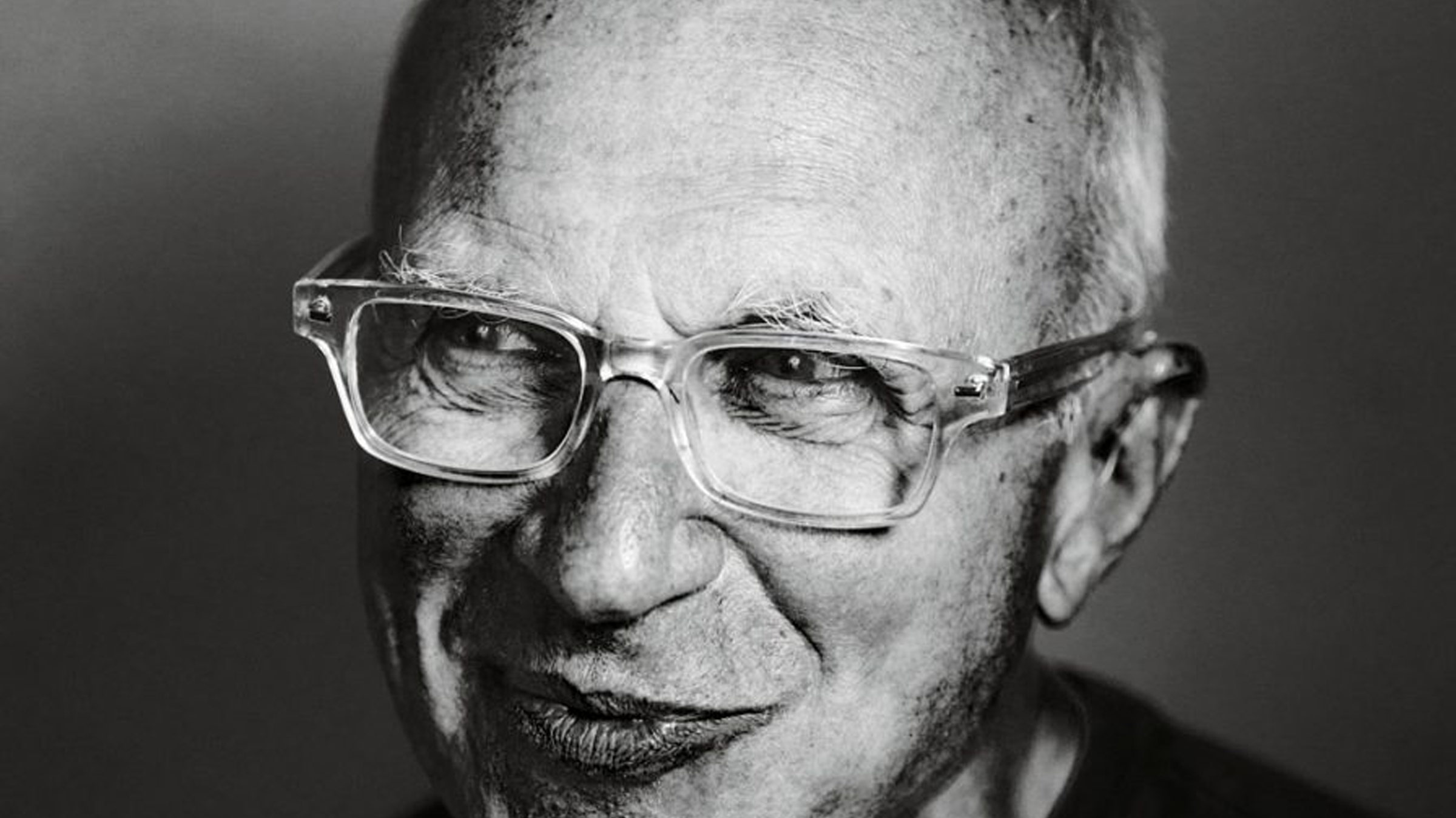

New York-based artist Stephen Posen and I met in his SoHo studio, with its faint smell of oil paint in the air—a place I’ve come to know well. In 1972, Posen’s photorealist paintings of cloth-covered boxes appeared at Documenta V with the blessing of swiss curator Harald Szeemann, inaugurating a key figure of American Realism. Over his 40-year career having been recognized in museum collections like the MoMA and the Guggenheim, Posen has continuously explored the line between the physicality of paint and pictorial illusion, and questioned the tension between our interior perceptions and exterior realities. He has traced a path through trompe-l’oeil compositions, to photographic mixed media and even pop, with the use of cartoon characters like Krazy Kat. In a solo-exhibition earlier this year he premiered a new body of work: pairings of photographs and a selection of paint-on-photographs. We sat down to discuss this new work and his ongoing struggle to merge photography and painting while Bozart the family poodle sat at our feet.

Above The Fold

Revelations of Truth

Class is in Session: Andres Serrano at The School

New Ceremony: Backstage Paris Fashion Week Autumn/Winter 2017

Conscious Skin

TIM GOOSENS—Let’s start with your photographs: What is your process? How do you decide which images to pair?

STEPHEN POSEN—I have been collecting photographs for a long time and they are always my own. I am compiling what could be described as an atlas. Besides its evocation of map-making, it relates somewhat to Gerhard Richter’s visual compendium. I’ve been intrigued by the explorations of Aby Warburg, the German philosopher-historian who made an attempt at an iconographic lexicon in his attempt to bridge gaps between pagan mythology and the Florentine renaissance. In my case, I try to edit my images down to pairs that I feel resonate structurally, metaphorically or spiritually. Today I spent the morning thinking of how to pair an image that I recently photographed. I probably looked through 4,000 of my images. I found nothing that was satisfying—visually, poetically, or as a photograph. I have always been a painter and using photography is an on-going challenge.

TIM—Is there a way you organize this atlas of images. Do you group them by trip?

STEPHEN—They are grouped chronologically by date. Time is a big factor. A lot of the photographs have references to the present and the past, like the pairing of the Egyptian cartouche in the museum and an ATM machine. Earlier this year, I hung twelve identical stills of a man from the 1929 movie Woman In The Moon by Fritz Lang in a stairwell. On each one, I added paint in a slightly different way and a word to construct the complete sentence “Do I really want to finance a trip to the moon.” It is about what actually happens when one has a thought. The words change in every still, and none of the drawings are identical, but the man in the photograph is always the same. It was a way to represent the passing of time.

TIM—In pairing the photos, do you feel you want to formulate answers to certain questions just as Warburg was trying to find answers?

STEPHEN—I very much like this sentence from Aby Warburg: “A ghost dance in which the most resonant gestures and expressions from the past return with spooky insistence suddenly casting whole new relationships.” I want to think about how I pair the photographs like this: a ghost dance. I don’t think there are answers and I don’t pre-plan my photos. When I am shooting, I may suddenly see some idyllic or iconographic element about a situation and I am thinking about what that might represent in opposition, in addition, or in conjunction with another image. Another aspect I think is important is a before-and-after concept that can be seen for example in the pairing of footprints in the snow and a landmine in Cambodia: the foot prints become a bit chaotic as they reach the bottom of the photograph and this is mirrored by the leaf pattern in the grass of the landmine image. These images imply a narrative that is more political than the others.

TIM—Is there at times a certain shame to overcome in taking idyllic images?

STEPHEN—I am very wary of stock images being sentimental. I am very conscious of what I edit through the lens. I like to frame photos so you don’t know what you are looking at and in that delay the viewer can move past a more conventional reading.

Most of life is like this: you can look and understand it, but what it means is open to many different translations.

TIM—When did you start doing those? Is the process the same? You go through the images you have and then you reserve some for pairing and the others trigger something for paint?

STEPHEN—One could say it started in the early 1970s, when I was taking a photograph, enlarging it to mural-size and placing strips of cloth, much like a drawing, on top. I would try to decide whether I was locating the strips within the photograph or whether the only possibility was for them to been seen as trompe l’oeil objects. The whole endeavor of trompe l’oeil in my work starts here. I would then paint a life-size still life of the composition. Following that, doing the Lexington Avenue windows at Bloomingdales in collaboration with my son Zac, was the most significant step that occurred. I began seriously photographing details of his clothing. I had just finished a show at the Drawing Center (2006) and collaged those drawings on top of the photographs. After that I thought, why don’t I paint this drawing on top instead. That developed into painting on top of movie stills like Woman in the Moon, Pépé le Moko (Duvivier, 1937) and The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles, 1942). If they were silent films I would use the subtitles as part of the painting. These functioned more like clusters rather then serial images. It felt very exciting: the photographs were spread on the wall, and sometimes linked by string, pointing to different places. Or I would use little pushpins. It was and still is an extremely difficult process because photos are spectacular and pure. When you use paint, it requires a transition to believe that you are actually putting it within the space of the photograph, and not merely on top. This continues to be an issue I have to grapple with every time I start a new work.

TIM—How do you decide on the scale of the paint-on-photo works?

STEPHEN—That is really a function of ambition and the ability of paint to reflect time, which on a smaller scale is much more limited. When I put the paint on the photographs it is part of an expression of some kind of time-element. For example, in Richter’s work, his gestural painting with a squeegee creates speed, directionality and implied time elements. You see the paint movement but you are looking through it as well. I think about what I do in a similar way but the way I put down paint is different. When I took the photographs, and blew them up I was looking for information around the perimeter of the photograph because I knew I was going to apply paint to the center. That has always been the approach that I took when I made them. All of this is probably also linked to my earliest experiences as an abstract expressionist in graduate school: I painted out of tin cans. I really like to move paint around, and when I paint larger I am closer to that experience.

TIM—I like your reference in an earlier conversation of ours to a review of the movie Tree of Life: “…the flow of images seems true to the texture of experience—the interplay of memory and immediate sensation, the coexistence of perceptual clarity and clouded understanding…”

STEPHEN—In regards to “immediate sensation” I think of paint and of memory: what can both appear and disappear in the image, which we must recollect and reconstruct. The “clouded understanding’ part lets me off the hook. It means I do not have to know what it means… And I think most of life is like that: you can look and understand it, but what it means is open to many different translations. In the photographs that I take these days I think I look for flexibility in their potential meaning.

TIM—This might be one of the keys to happiness: to understand life, but to not get frustrated when its meaning is unclear. There can’t be any frustration. I think there was a point, with paint—exclusively with paint—where I felt like Malevich. The thrilling satisfaction of knowing that you could not do anything else to perfect a painting, I don’t believe any longer. There is always a movement of the hand that changes everything. I’ve made many paintings since that time. My demands and sense of the world are greater and different: it is an imperfect place, open to variations and errors, incidents and accidents. It is interesting that in photography you have the tools to make the perfect object, to convince someone that what you are looking at actually happened. On the other hand you can enhance it in ways that are similar to painting: no matter how you enhance it, it is never perfect. It is always a variation and never definitive.