Charles Renfro discusses how to build nothingness with Rio's rising architect Carla Juaçaba.

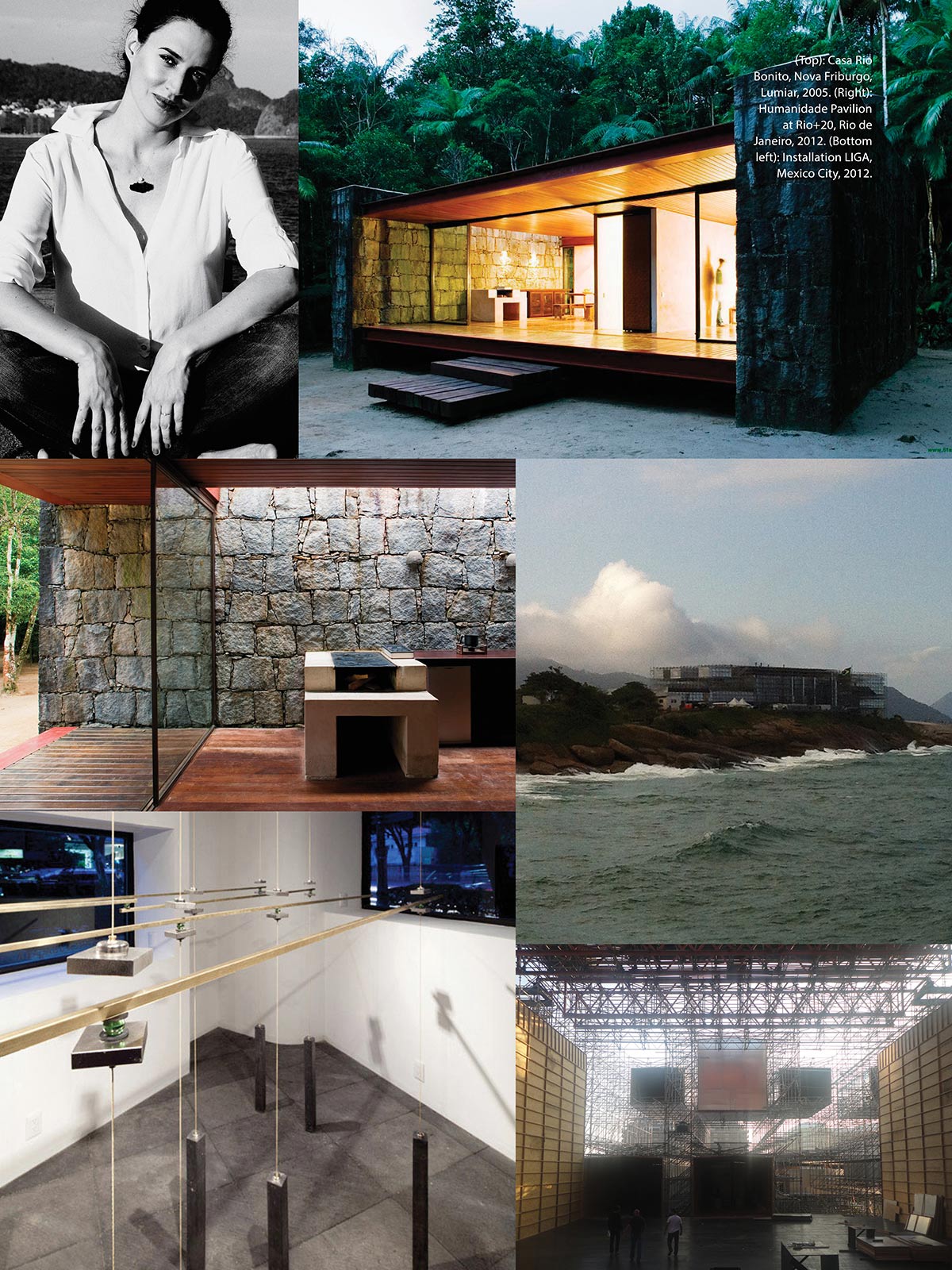

The world has its eye on Brazil, with the World Cup taking place there this year and the Summer Olympics arriving in 2016. The South American country has also produced a rising starchitect. Despite working in a field dominated by men, Brazilian architect Carla Juaçaba has made a name for herself through her thoughtful designs that fuse functionality, beauty, and sustainability. She recently won the inaugural arcVision Prize, for projects like the Pavilion Humanidade, which was built in 2012 in Rio de Janeiro for the United Nations sustainability conference Rio+20. Architect Charles Renfro of Diller Scofidio + Renfro chats with Juaçaba about her practice, life as a female architect, and the execution of Pavilion Humanidade.

Charles Renfro: Brazil has been on my mind a lot—there’s so much happening there. I’ve been impressed with your work since seeing you speak at the Latitudes conference at the University of Texas in Austin. It made me think about the challenges and opportunities of working as a woman architect in Latin America, and Brazil in particular. In 2012, you won the inaugural arcVision prize, awarded annually to notable female practitioners in architecture. You were selected from an outstanding field of international applicants by an all-female jury, who applauded the courage and creativity of your work, the Pavilion Humanidade especially. The pavilion was beautifully conceived and executed—elegant and ephemeral—and reminded me of some of my studio’s temporary work, especially the Blur building in Switzerland.

Carla Juaçaba: I actually didn’t originally receive the commission for the Pavilion project. The site, in between the Copacabana and Ipanema beaches in Rio, is a place where they’re always building temporary structures, usually plastic tents for events. The organizers of the Rio+20 sustainability conference wanted to build something there for the convention, and invited the theater director Bia Lessa to be the designer. They invited her because of her work in exhibition design, and asked her to do that sort of thing in the interior of a temporary building—essentially just a plastic tent with an air conditioner.

She said, “I’m not going to do that, because it has nothing to do with the content of the conference. I want to work on this with an architect.” The first person she called to do the project was Paulo Mendes da Rocha, who had worked with her on some theater design in the past, but he was busy with other work. So she called me—not to invite me to participate, but to ask if I knew an architect who works in sustainability.

I told her that we should talk. We met at the site, where one of the plastic tent structures was starting to go up over some scaffolding. I got rid of the plastic and continued the construction of the scaffolding walls from five meters to 20 meters high—five walls, each 170 meters long. So much of the design was already there from the start—the scaffolding, the space between the walls. It was already so beautiful; you saw straight to the sea through a massive, gridded structure. We needed the ramps and exhibition rooms to complete the building and to support and strengthen the walls.

Charles: Did you work with an engineer?

Carla: We had an engineer. But we didn’t have too much time. We kind of designed as the project was being constructed. But it worked because it was a modular structure. There was no study of form, only a proposal of how to fit everything in. The problems changed 1,000 times, but the plans adapted easily. After the project was completed and published, I received emails comparing the project another unique architecture—to your Blur building. I think the presence of history is there, but the intentions were different. I was more fascinated by building the scaffolding—by constructing a huge wall with no physical density.

“So much of the design was already there from the start: the scaffolding, the space between the walls.”

Charles: I’m not suggesting a premeditated connection, but that’s partly what happened with Blur—space as ephemeral, architecture as atmosphere rather than object. In the case of your pavilion, the atmosphere develops from the aggregation of thousands and thousands of pieces of pre-manufactured scaffolding, an unglamorous material that you turned into something much more significant.

Carla: Were you able to see it?

Charles: I wasn’t able to see it in person, unfortunately—only through photographs. In a way, that’s the charm of the temporary structure: it disappears into the archives of disciplinary memory and becomes something of a myth. In a way, this myth lives a fuller life than a permanent building. It informs new kinds of practice, including that of the architect who designed it—you don’t have to be exactly true to it in the end. You can carry the ideas of its conception even as your work changes, grows, and turns down unexpected paths.

Sustainability is a central tenet of your practice, in particular the sensitive use of materials. You design projects to use just the right amount of material; to be just big enough to do what they need to do. This idea of judiciousness—of doing just enough—seems to have a long heritage in Brazil. I’m thinking of Lina Bo Bardi, in particular—a brilliantly judicious architect, one of the greatest architects of her generation, who also used salvaged materials in her work. This understanding of sustainability is so different than the buzzword-version that often gets talked about, “how to make your air conditioning system greener,” “tips to harvest solar energy from the 10,000 square-foot roof of your single-family home,” that sort of thing. What you’re doing, in contrast, is encouraging people to live in a sustainable way—not just consume in a “sustainable” fashion.

Carla: I think that Lina arrived as a foreigner, but was not really a foreigner. She knew how to adapt to the conditions of her work—of site, of economy. She had ideas that came from the Italian Arte Povera movement. With my work as well as hers there is a perception of economic conditions and embracing of the possibilities that I have in hand. I’m not going to think about something that I don’t have in hand. Take the Pavilion Humanidade, for example: with Copacabana as the stage of Brazil, there is constantly scaffolding being built and dismantled, so when I went to the site, I thought, “I’m going to build this out of scaffolding, of course.” With my stone houses, there was the same sense of economy—the client didn’t have any money, so we used locally-sourced stone.

Charles: One of the things that’s beautiful about your work is the sourcing of materials from the site itself—the stone, for example. In one of your houses, the brick was made locally and the building was constructed by local craftspeople. This sensibility is at once rugged and sophisticated, an extension of Modernism but with a poetic overlay, a tectonic poetry.

I find Brazil a place that is humble in spirit and deeply cosmopolitan at the same time. In some ways, your work can be read as a metaphor for this dialectical cultural condition. Your design for Casa Varanda, for example, on the outskirts of Rio: building with steel seems antithetical to building in the jungle, but in calling for the least amount of material, this choice allowed for a design that was least impactful on the site. There’s a compelling dialogue between the tectonic—the machine—and the natural—the site—that gives your work a particular position that I think is distinct from a lot of global practice. Does the idea of architecture as metaphor for country resonate with you at all?

Carla: Yes. Take the favelas, for instance: they are constructed and dismantled, constructed and dismantled. You find something beautiful, and then next week, it’s not there anymore. You see a gorgeous staircase, and then it’s gone. Maybe it’s true that design methodology is determined by the country itself—in Paraguay, for instance, the architects all work with what’s at hand.

Charles: I want to go back to the question of women in architecture. I asked colleagues in Brazil to name a few of the most promising female architects; your name was at the top of the list, along with Marta Moreira of MMBB and Carolina Bueno of Triptyque. Are you all close as a group of female architects? Do you even consider yourselves a group?

Carla: I only just met Marta recently, at a workshop with Eduardo Souto de Moura. She works with a generation of architects who are more connected to São Paulo than to Rio. The question of women— it’s a difficult question to answer. The arcVision prize, for instance, is wonderful—a celebration and remembrance of the history of unrecognized women. But the truth is that I am always amazed by how women still hide themselves in what society expects. It is true that it is hard to find our own voice, but often times it is our own fault. We are afraid to be ignored, neglected, as I am sometimes myself.

Charles: Maybe that was my romantic misreading—I thought there might be a greater sense of bonding, a shared dedication to advancing women in architecture, but others have also told me that this doesn’t really exist in Brazil. There are lots of female architects in the U.S., but so often they’re attached to male partners or working under all-male management. It’s encouraging that even in Brazil—a place with perceived gender inequality in the workplace—women can have thriving practices.

Many of the concepts of high Modernism, itself a discourse traditionally dominated by men from the Global North, seem woven into the material and tectonic methodology of your work. Do you feel connected to the Modernist tradition?

Carla: I really like the work of the Modernist Sergio Bernardes, but he’s not very well known. He’s from an older generation of Brazilian Modernism, and his work— his houses as well as his public buildings—is very strong. There’s an environmental aspect to all of his projects: he would fabricate beams, for example, on the actual construction sites. I would consider him a Modernist, but he’s more interested in site and materials than the Rio Modernists.

Charles: So, more of a vernacular of Modernism—something that came out of local conditions. As architects practicing within an international canon, it’s a way of understanding ourselves that reconciles the idea of working locally and sustainably with the social and formal imperatives of the discipline as a whole.

I want to talk about Brazil in a broader context. The country’s middle class has been growing rapidly. In WWII, when many architects arrived from Europe, including Lina Bo Bardi, there was virtually no middle class. There was the aristocracy, and there were the people.

Carla: Yes.

Charles: Did architecture play a role in establishing that? Your work, for example, is relatively inexpensive but also incredibly thoughtful. It engages a new kind of client who normally wouldn’t have considered commissioning an architect.

Carla: There are some architects in São Paolo that make large, ten-room houses, working solely for the upper crust of society. I’m really glad not to be doing that. It doesn’t interest me. There was a client who tried to commission one of these architects for a project, and the architect told him, “No, no, go to Carla,” because he didn’t know how to work with less. After the Pavilion Humanidade project, I’ve been working on different types of projects—a hospice and a palliative care facility, for example. The hospice will be the first of its kind here. I had to go to England to visit similar facilities there because Brazil just doesn’t have any legislation for creating these places. It’s a well-funded project—they have the money to construct everything. But I want to have the same position on materials and the working site that I normally do in my other projects. When given money, it’s easy to build expensively, chicly, elegantly. But I don’t want it to feel as if I had too much money to construct this. I know it’s not cheap to construct a hospice, but I’m sure they’re looking for it to be simple. Maybe this is an ethical position, and the consequence is aesthetics.

“[The favelas] are constructed and dismantled, constructed and dismantled…You see a gorgeous staircase, and then it’s gone.”

Charles: That’s a great point, to almost trick yourself into thinking you have less to work with than you do. It focuses your work on the judiciousness of the practice, on making choices that are simply executed without being devoid of poetry and design. It makes sense that you would be chosen to make a hospice because they are places where people need to feel calm, where it’s helpful to feel a connection to nature. It’s an excellent opportunity to expand the reach of your practice—to help others through the simplicity and elegance of your design work. Is your studio growing?

Carla: I have six people in my office. It’s huge.

Charles: That’s a real office! You also have work outside your firm: you teach, you write, you curate.

Carla: And I work in exhibition design.

Charles: Our work at DS+R is also multidisciplinary, and many of us teach, publish, and design outside of the office. Do you consider this work necessary for money, or necessary to expose yourself and others to a wide range of critical thought?

Carla: It’s necessary because building a house is never enough. I like working in exhibition design because it has the same budget and it’s faster. When I studied architecture, I never worked in an office because I hated creating CAD drawings, so I found this woman who came from a generation where she could be an artist and only work on design exhibitions. I worked with her for years. I was really happy with that. She was fascinating. I wanted to work with someone like that, outside of the office environment. I really never thought I would work in architecture—it just happened, very naturally.

Charles: Where do you see yourself and your practice going in the next few years?

Carla: I hope that this hospice project generates similar commissions. It’s the first time I’ve worked at such a large scale. The Pavilion Humanidade was a project with no details, almost no drawings. It could have been a written project. This is the first time I’ve suffered with so many drawings and details. But I also hope to continue building houses. Any project is good, really. I just want to work.

This article originally appeared in Document’s Spring/Summer 2014 issue.