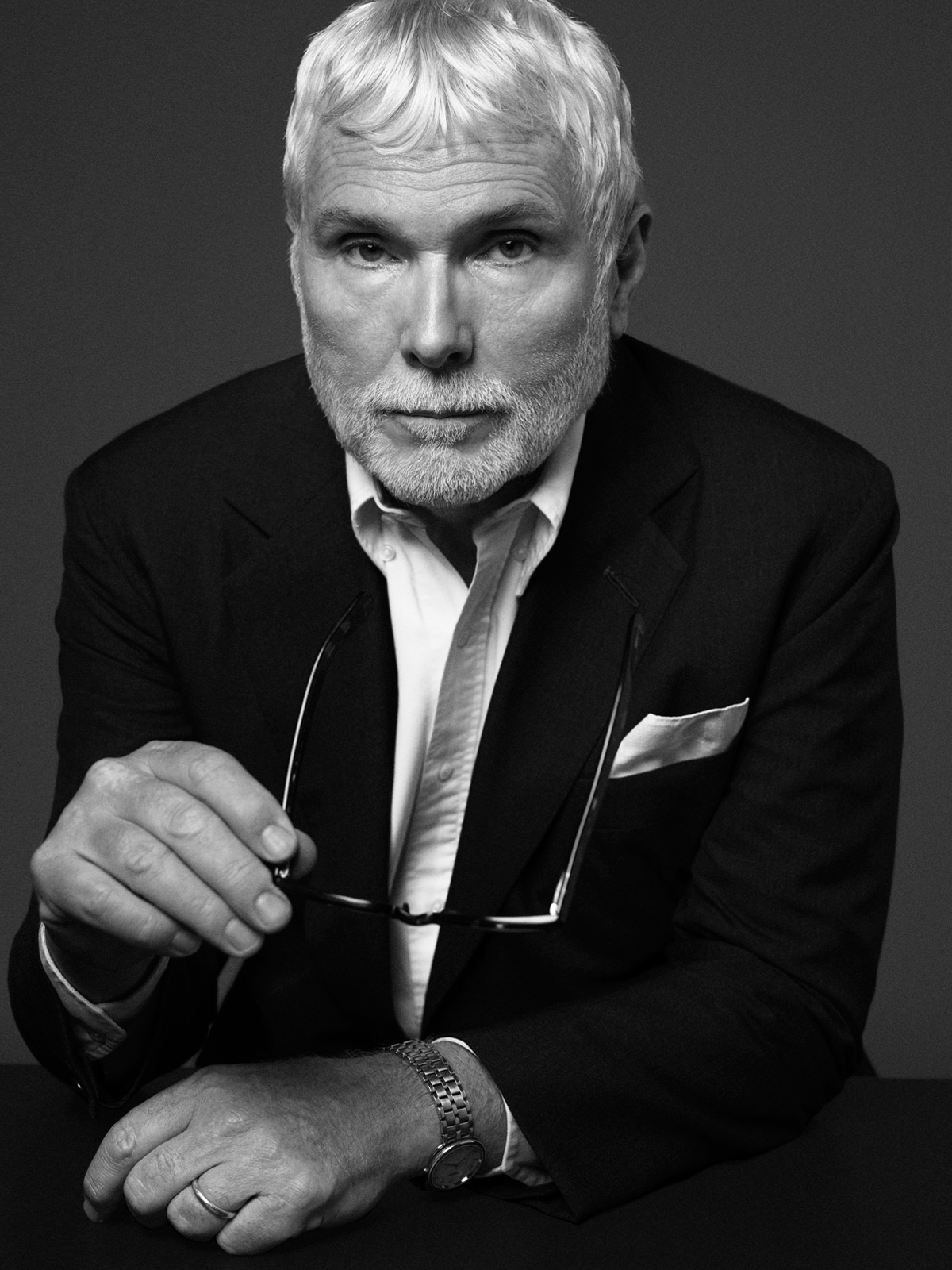

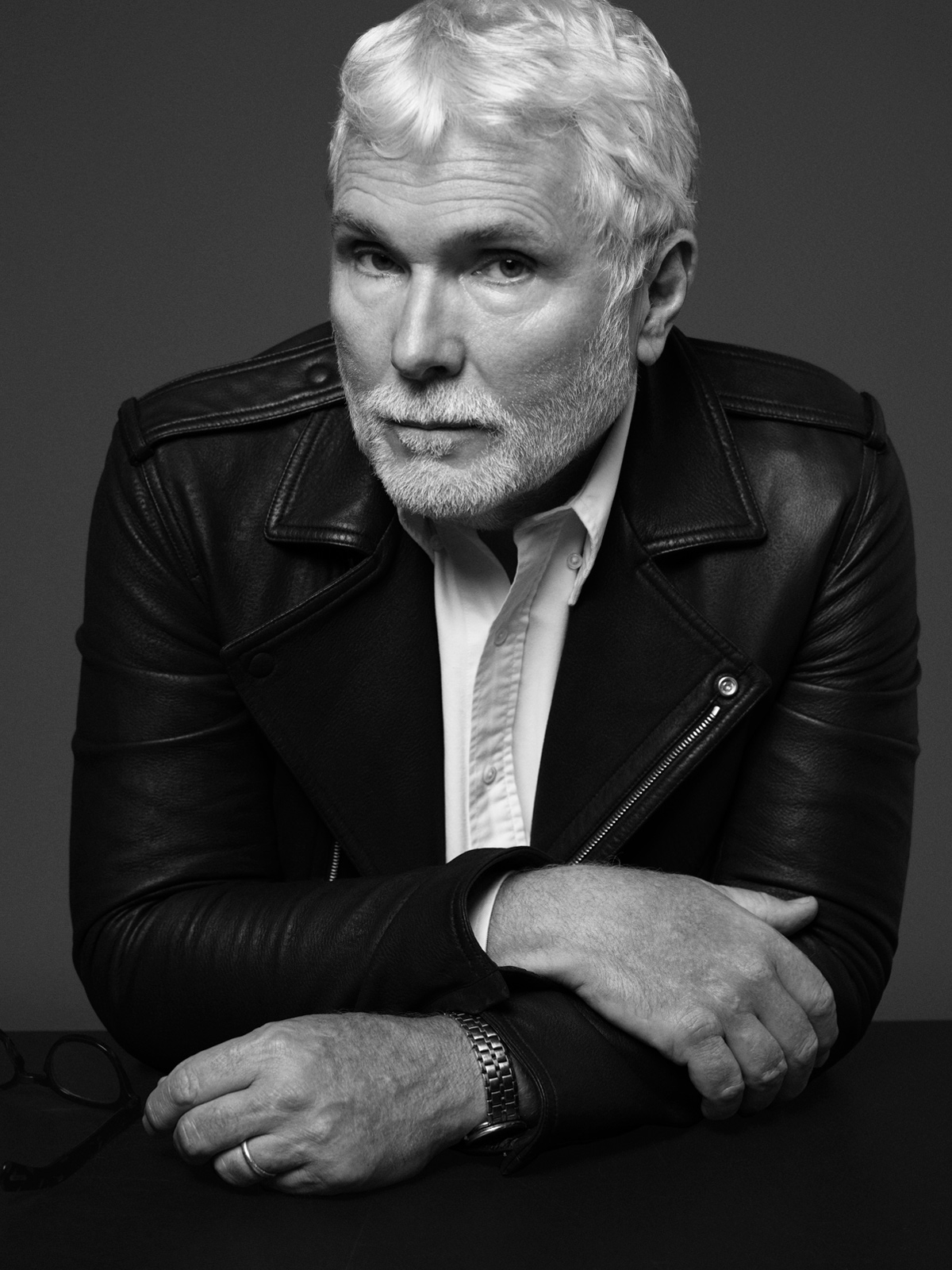

How Glenn O’Brien’s ‘TV Party’ ushered in the do-it-yourself entertainment era, from Document's Fall/Winter 2013 issue.

Seated in a makeshift studio—albeit one furbished with cushioned benches, tapestry-covered walls and carpeting—at Chinatown nightclub Le Baron, Glenn O’Brien faced a camera one February evening and announced, “Hi and welcome to the miraculous resurrection of ‘TV Party,’ the TV show that’s a cocktail party, but which is also a political party. It’s been almost 30 years since the original ‘TV Party’”—here he paused because of snickering from those on set—“but now, thanks to the terms of my parole, I’m allowed to be on television again.”

The first episode of the public access cable TV show aired December 18, 1978. O’Brien had recently appeared on East Village Other contributor Coca Crystal’s “If I Can’t Dance You Can Keep Your Revolution.” Strangers approached him on the street to say they’d watched, and he promptly recognized the boob tube’s reach.

Filmed at ETC Studios on 23rd Street, the perhaps inadvertent opening scene of “TV Party” was a shot of three empty, mismatched chairs. A sweatshirt-clad arm (in front of the lens) steadied the camera, and after umpteen zoom-ins and zoom-outs, signs reading “Glenn O’Brien’s TV Party” and “Live from N.Y.C.” blinked at no precise interval on the screen. O’Brien greeted the packed space and his at-home viewers with what turned into his go-to salutation: the “cocktail party … political party” line. A single person applauded; the rest were either unsure of audience demeanor or stoned, but positively not fans of the Man. By the time he delivered his monologue on President Jimmy Carter’s attempts to suppress the new wave, the party had started.

“I liked the idea of mixing entertainment with some kind of political discussion, because it was the Carter and Reagan era, and things were bad politically,” O’Brien explains. “The interest rates were about 20 percent. New York was broke.”

Insofar as entertainment, his premiere guests included Robert Delford Brown, the founder of the first art religion; lead singer of the B-52s Fred Schneider, who recited poetry from his junior college final project in creative writing; punk pioneer Andy Shernoff; and Gregory Fleeman, who sang about skin and morons. O’Brien also played a contrasty tape of Robert Fripp, Debbie Harry and Chris Stein, and produced his debut call-in segment, which, from its inception, should’ve been dubbed the “hang-up” segment.

“I’d rather read people’s rude Tweets than deal with them on the phone.”— Glenn O’Brien

Stein soon assumed co-hosting duties. Fripp and Harry became TVP regulars, along with Patti Smith keyboard player Richard Sohl, Fab 5 Freddy and Jean-Michel Basquiat, who often operated the character generator, typing in SAMO-esque proverbs such as “DEATH IS ROLAIDS” and “GAMMA RAYED PROSTITUTES LOOKING TO A CROWD OF FISH ON BEING A DOG.” Walter Steding led the TV Party Orchestra. “Andy Warhol came once,” O’Brien recalls, then launches into a list of boldface names: “David Bowie, Iggy Pop, Steven Meisel, Robert Mapplethorpe, Chris Burden (the artist), the Screamers, George Clinton, Funkadelic, the Brides of Funkenstein, Jeffrey Lee Pierce of the Gun Club.”

A peril of live programming, O’Brien needed a vaudeville hook to pull several invitees off-stage. “On two occasions, we pretended that the show was over, and when the people got up and left, we went back and continued,” O’Brien says. “One was Legs McNeil—he was with Tom Baker, an old Warhol superstar—who seemed to have had a considerable amount of mind-altering substances before coming to the show. The other was a punk band from San Francisco called the Mutants.” Reason for removal: “They were being rude and difficult, and I wanted to move on to something else.” Still, influenced by Hugh Hefner’s “Playboy After Dark,” and “Tonight Show” host Jack Paar, O’Brien kept TVP’s format loose. “If there was planning, it was creating a theme that would inspire people to come in a specific mode of attire—like we did the Primitives show, and everyone came dressed as savages,” he remarks. “Or we did the Middle Eastern show and everyone came dressed as Middle Easterners. Sometimes, there would be music that would fit in with the theme, but the [week-to-week] planning was mostly figuring out who was going to be on the show.” A handful of episodes were prerecorded at counterculture hangouts like Mudd Club and Danceteria, where O’Brien and co collected the door money.

“The key thing about ‘TV Party’ was the start of the do-it-yourself sensibility, which now is pervasive,” says Fab 5 Freddy, né Fred Brathwaite. “Now, it’s easy to do things yourself and put it online, say, but then, there weren’t many opportunities to do that.”

Brathwaite, a reader of O’Brien’s column in Interview, initially asked the gadabout pre-TVP to swing by his own program on Medgar Evers College’s radio station. A couple of months later, he joined O’Brien at ETC Studios for the inaugural production. “I was one of the original cameramen,” Brathwaite notes. “Somebody who was supposed to have operated one of the cameras didn’t turn up, so I got to do that quite a bit in the very beginning. I was also a frequent guest.” He describes his first experience in the mismatched chairs as nerve-wracking. “I was sitting next to David McDermott. He used to dress as though he was living in the late 1800s, from head to toe, as part of an organization called the Salon D’Art Society. He was going on and on, and then he said he wanted to remake ‘Gone with the Wind,’ and he mentioned something about wanting me to be in it, and I was like, Whoa, is this guy trying to say I should play a slave? So then I said, ‘Yeah, I’ll be Rhett Butler,’ which got a laugh.”

Eccentric McDermott aside, Brathwaite, who went on to achieve international renown as the host of “Yo! MTV Raps,” adds, “Glenn was encouraging of things I was trying to figure out—making art, taking graffiti into galleries and hip-hop music and culture. And through the show, I met people like Chris [Stein] and Debbie [Harry], who became big supporters of my work, and many other players on the scene … dozens of good people. We’d all socialize together. If someone had a band, we’d go see who was performing. People had art shows; we’d do that. People made films; we’d all be there to see them.” From 1980 to 1981, “TV Party” went on hiatus to make a film. The O’Brien-written “Downtown 81” starred Basquiat, featured the show’s director, Amos Poe, and was directed by TVP cameraman Edo Bertoglio.

“TV Party” graced public access until 1982 with approximately

75 episodes broadcast. In 2005, Brink Films released a documentary, which brought new attention to old footage, followed by DVDs of selected episodes. O’Brien noticed, based again on a street census, that he was being watched. “It got popular on YouTube, and then, a few years ago, Olivier Zahm from Purple and André Saraiva, the nightclub king, were trying to talk me into doing it again with them,” he says. “I kind of got dragged into it, but it turned out to be quite fun.”

Saraiva identifies as a longtime “TV Party” enthusiast. “It had a cult following and featured so many of my idols,” he shared via email. “I remember my friend Paul Sevigny had a tape of the show and we watched it together. [However,] we are not doing this out of nostalgia. ‘TV Party’ is a platform for freedom of speech and creativity. Glenn is the godfather and it has the same spirit, irreverence and open mind as 30 years ago, with a contemporary feel and point of view.” On February 6, Saraiva lent Le Baron to the cause. Stella Schnabel, Inez & Vinoodh, Waris, Hailey Gates, Maripol, David Blaine, MGMT’s Andrew VanWyngarden, Jeremy Kost and Brathwaite stood out amid the crowd summoned to the “pilot” taping.

“The energy of the room felt right,” Brathwaite comments. “There were about five or six cameras floating around—small, compact, technologically advanced cameras.”

“I’ve never been a generation gap kind of person; I think that’s really bullshit.” — Glenn O’Brien

Talk segments and a dozen or so performances became interspersed postproduction with clips of attendees outside the door on Mulberry Street and bits of conversation in the club picked up by roaming microphones. “It’s more like what I wanted to do but didn’t have the means to do, in the first place,” O’Brien says. “A lot of what ‘TV Party’ was originally had to do with the fact that it was done live, for almost no money, in the studio. But this was like a real party and people had drinks and there was quite a lot of people instead of a small number of people.”

Although he referred to the political aspect of the revived “TV Party” as subliminal right off the bat, O’Brien wondered in front of a panel that included Joan Juliet Buck, GQ’s Michael Hainey and journalist Hooman Majd whether cable could be an alternative to government, “because it’s always been my theory that television is the government and what we see in Washington is merely the top-rated show.” In a different part of the pilot, O’Brien told collage and graffiti artist Nate Lowman, “I think New York should just be its own country. Texas wants to split off—see ya later.”

Lowman responded, “I only moved to New York in the ’90s, but for the first four or five years, it didn’t feel like it was America. When the World Trade Center fell down, all of a sudden, the rest of America decided that New York was their property because it was significant American soil.” He drew a comparison to Hawaii and Pearl Harbor.

Artist Dustin Yellin, designers threeASFOUR, Chromeo with DJ A-Trak and artist Tom Sachs had their moments on the cushioned benches. The latter pitched a scheme to cultivate opium poppies on Mars.

Meanwhile, the night’s musical guests spanned the aural spectrum. Among them: electronic dance group Light Asylum; Devendra Banhart with OG TVP co-host Stein; semi-screeching, pint-sized songstress JR; the Unstoppable Death Machines feat. Ben Robey aka Ninjasonik; Schnabel’s friend Lauren Kramer, who executed a rousing rendition of “My Funny Valentine”; Tigga Calore in a Batman poncho spitting seriously fast raps; and, of course, Harry, who cooed a number dedicated to O’Brien.

If it wasn’t clear from the pilot’s lineup, O’Brien thrives on uniting unlikely combinations of creatives. “I’ve never been a generation gap kind of person; I think that’s really bullshit,” he says. “I believe in a bohemian class of people that is multigenerational, and I like having a lot of variety in the same room. I wouldn’t want to have a show that was all straight or all gay, or all 60-year-old or all 20-year-old.” For the second episode of “TV Party” resurrected, he had a lot of variety in the same hotel room. Taped at the Lafayette House in late April, O’Brien held court from a queen-size bed, and Cintra Wilson, David Spade, Japanther, Eric Goode, UFO, Vincent Kartheiser, Quentin Jones, Michael Portnoy and more visited. A third episode, “TV Party Goes to Camp,” is in the works.

Excerpts from the pilot and PJ party are online at www.tvparty.tv, but O’Brien isn’t sure where the full programs might live. “I’d love it if it were on a major cable outlet, but by the same token, I think the whole thing is changing,” he points out. “You have Netflix; Vice has a successful channel. Wherever it can have a happy relationship with who’s presenting it, it’ll be OK. People who are interested in it will find it.”

He goes on, “When I was a kid in Ohio, I would watch certain TV shows and they made me want to move to New York. Probably most of all ‘What’s My Line?’ which was a game show, but the celebrity panelists were all really clever, witty people. That’s gone, you know? You watch TV now and it’s all Hollywood, but I think by watching this, you really get a feel for what New York City culture is.”

However, viewers will have to make do without a “TV Party” staple: the call-in segment.

“I’d rather read people’s rude Tweets than deal with them on the phone,” O’Brien says. In other words, as if there were a doubt: The Internet killed the public access star.

Hair Leonardo Manetti at Tracey Mattingly. Make Up Ayami Nishimura. Manicurist Ami Vega at Marek & Associates. Digital Operator Jeronimo De Moraes at Dtouch. Photo Assistants James Garrett and George Valenzuela. Location and Equipment Bathhouse Studios.

This article originally appeared in Document’s Fall/Winter 2013 issue.