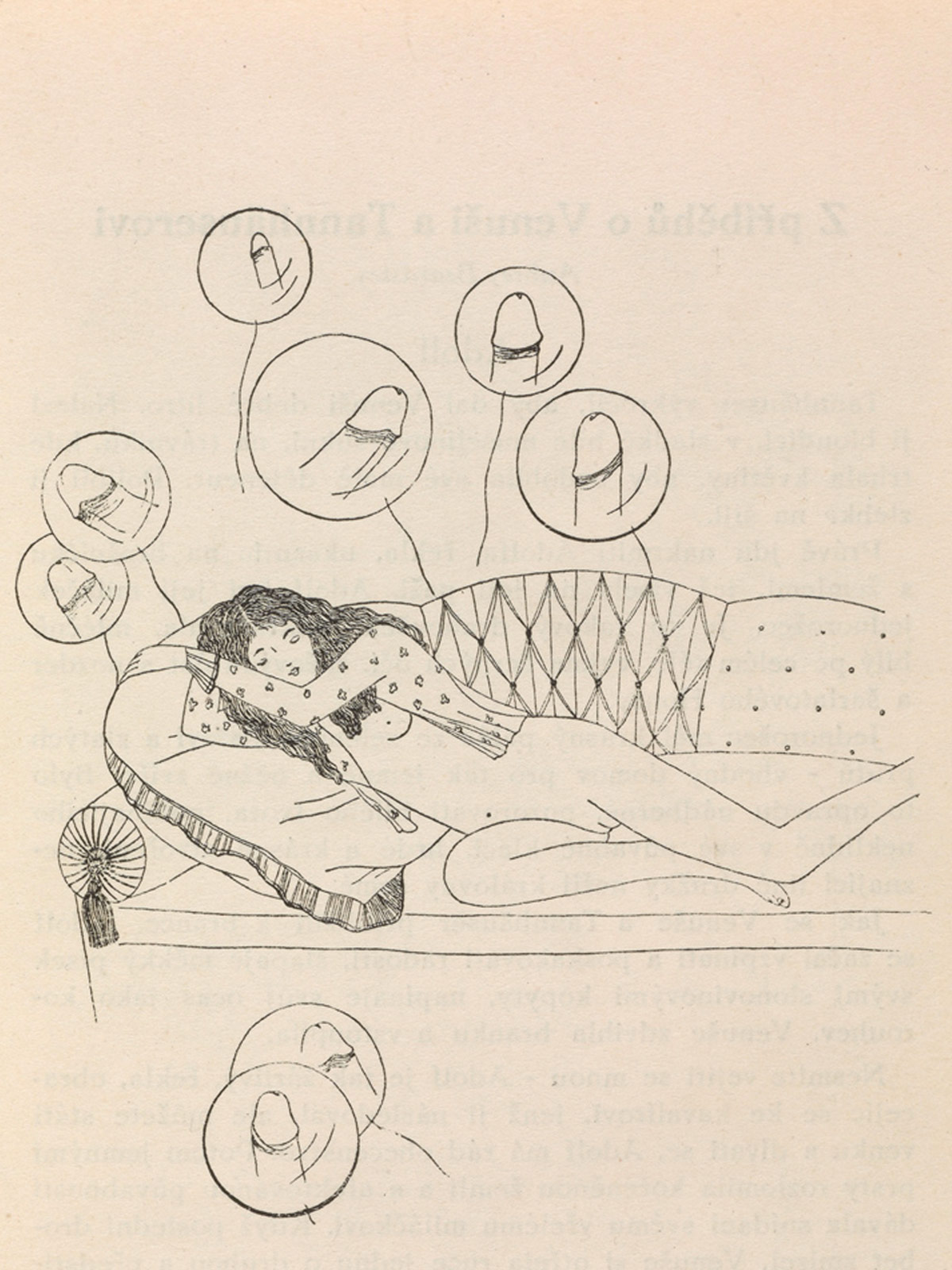

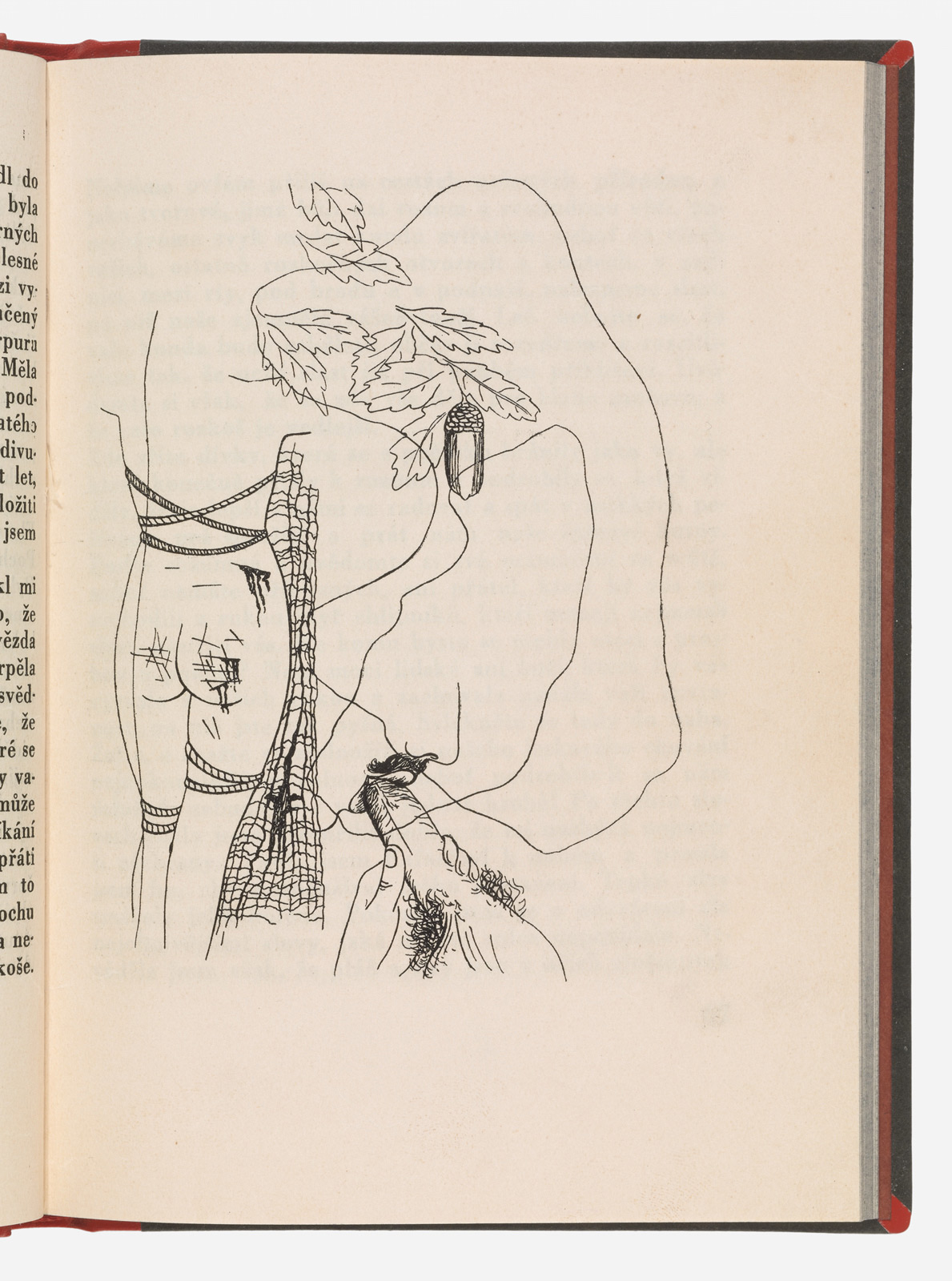

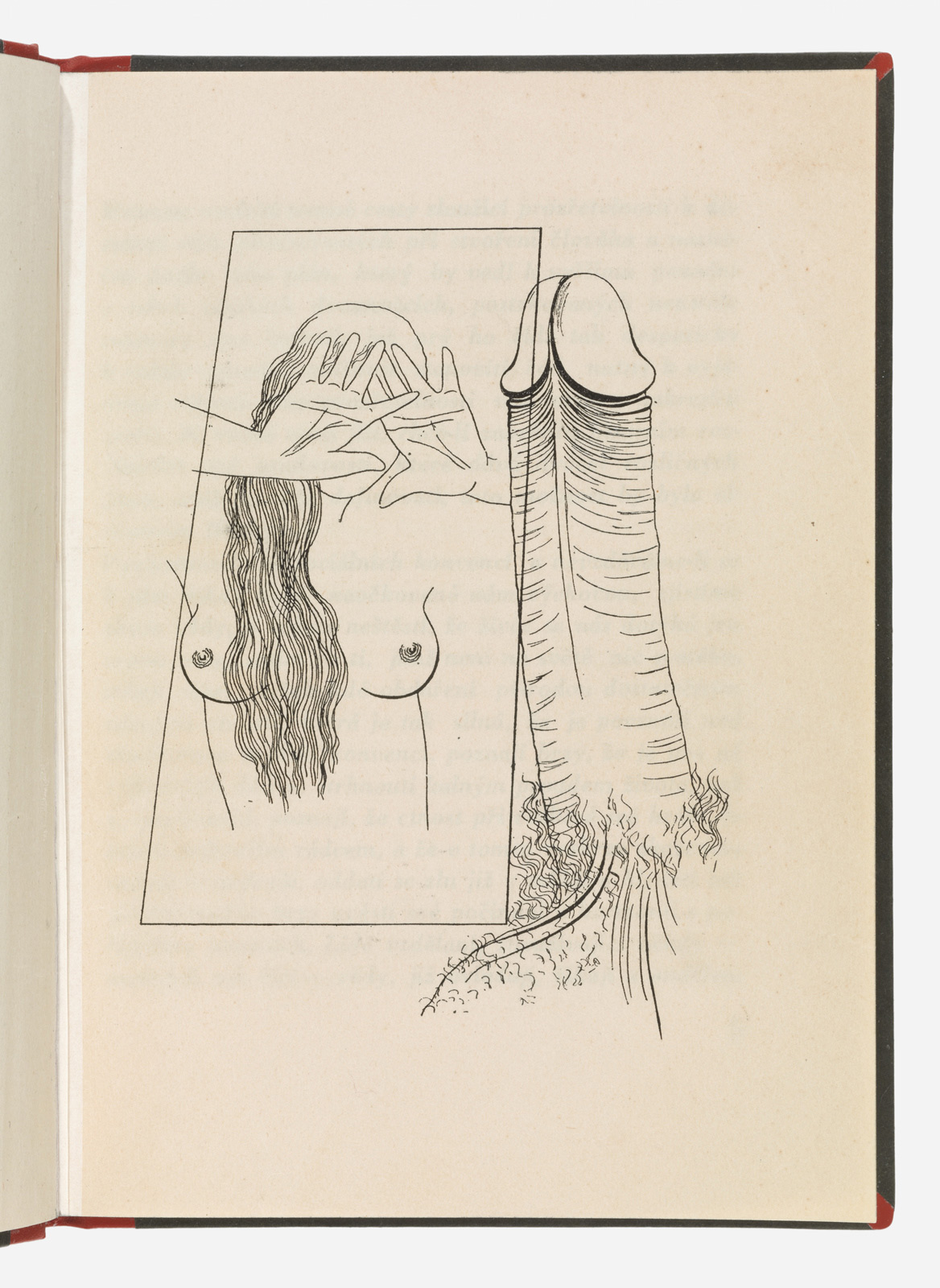

A dark commentary on female sexuality interpreted by the works of two artists from very different time periods, Toyen and Emily Sundblad, from Document's Fall/Winter 2013 issue.

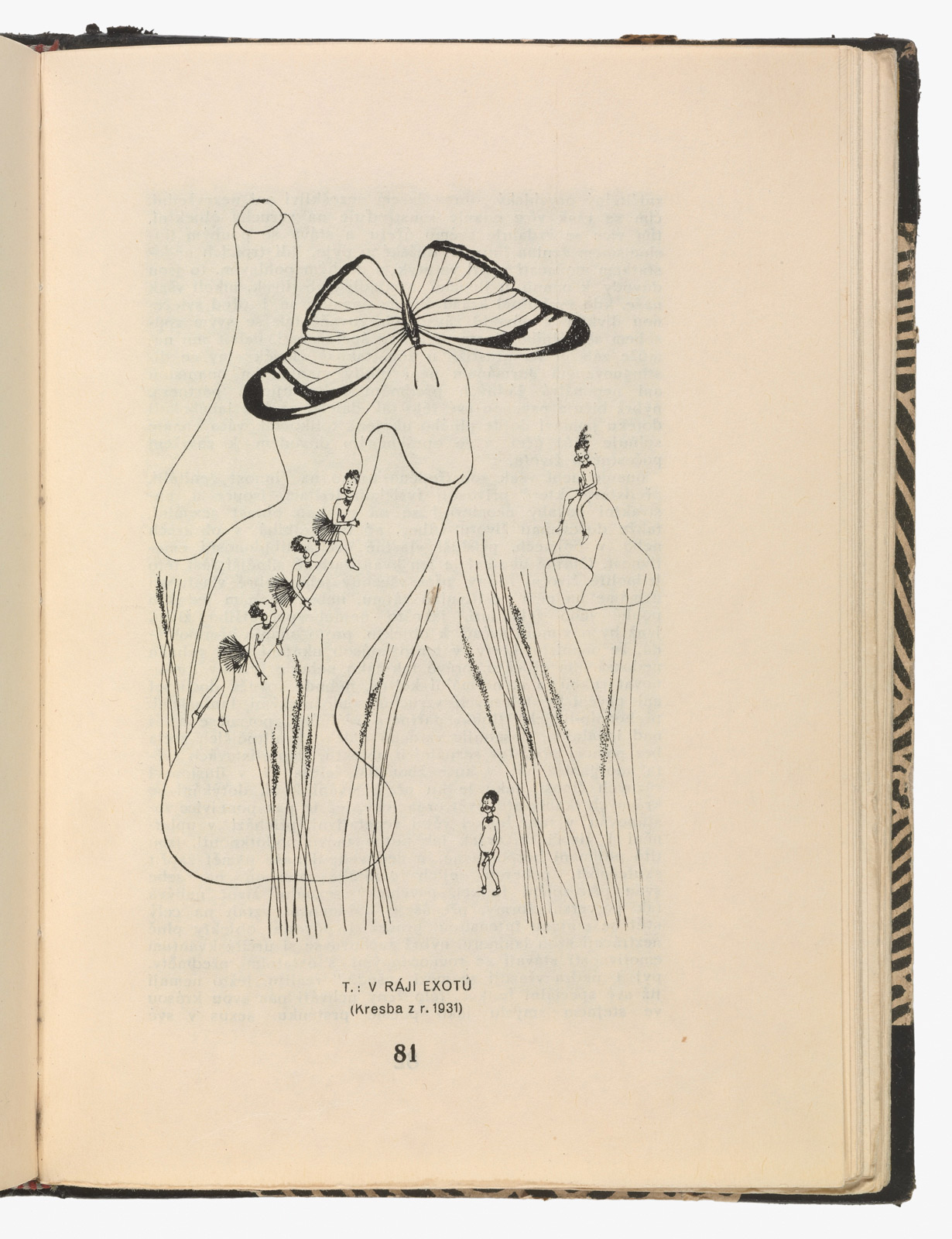

Though little-known outside of Europe, the paintings and illustrations of Czech artist Toyen (born Marie Čermínová in 1902) offer a particularly salacious take on the surrealist agenda. Spanning from the early 1920s until her death in 1980, Toyen’s work alternates between darkly coded symbolic depictions of female eroticism and overt references to sadism, masochism, and satirical interpretations of the mid-section between culturally sanctioned femininity and masculine fantasies of feminine desire. Nearly a century after Toyen began making these works that alternately shock, frighten, and amuse, artist Emily Sundblad made a group of drawings that (although not specifically created to enter a dialogue with the drawings of Toyen) offer a wry and sometimes disturbing commentary that follows a nearly identical vein.

These strangely twinned bodies of work both liberate and constrain via their respective treatment of female sexuality: a two-pronged approach that frees each subject to be both libertine and slave, the ghost and the haunted. The following portfolio of drawings from both artists and the accompanying text investigate the concept of overlap, the frightening and exhilarating idea that there are doppelgängers, both conceptual and literal, circulating through time and waiting to find their matches, waiting to become a pair.

HOW THEY MET THEMSELVES

Before I bored you, I frightened you. “You scare me,” you told me once. “You are the emptiest person that I have ever known,” and I saw the shadow of your hand passing over the bandages that I had wrapped around my face, a test of my vision, a test of my commitment. “This one makes me feel like I am talking to a false wall,” you whispered in my ear, leaning close and breathing hard, your fingers questioning the tension of the garter belt I wore beneath a Joan Crawford Exiting Through the Backdoor of the Plastic Surgeon’s Office fur. “It’s perfect.”

The disguises sometimes even tricked you; I could pass you in the street, panhandle outside of your apartment, sit across from you on the subway and not even the faintest flicker of recognition would pass over your eyes. “I followed you today,” I would tell you at night, and you would grab my arm, pull my head back and put your hand in my mouth to feel around, your fingers stretching my skin to its limits. “You are nothing,” you would tell me, pushing against me with too much force and turning out the lights. “You are nothing.”

After a while, I stopped going to my appointments; the agency would call and I would listen to the instructions pouring out of the answering machine on your kitchen counter, increasingly irritated receptionists detailing what the client had asked for, offering me small biographical details that were meant to help my performance before carefully reciting the addresses of vandalized apartment buildings or hospitals or penthouses on Park or Fifth. I would sometimes go to watch, scan the building for who had requested a whore with a stutter or a burned face, who had asked for a prison nurse, who had been dreaming of Roberta Porter, a student teacher from 1963 who smelled of vanilla coffee creamer and had a lisp.

After a while, I was only following you. I wanted to be with you, I wanted to listen to your phone calls and see the women you chose for yourself, women who you couldn’t pass your hand through, women who had reflections and phone book listings and bank accounts registered under their real names. “You gave yourself away today,” you started telling me. “I smelled your perfume on a black whore at Sable’s, Annie. I knew it was you right away,” and you brushed a hand over my head. “Your wig needs to be washed,” you told me, walking away and not looking back. The beginning of the end.

I stopped working last spring. I keep two adjacent lockers at the Port Authority Bus Terminal that are overflowing with wigs and makeup and keys that are no longer linked to working addresses; there are knotted strands of hair and colored powders that fall through the vents when I slam the metal doors, there is $5,000 inside the hollowed-out pages of a Danielle Steel book that I took from the lobby of a women’s shelter. I have started wearing gloves and the combination lock slips perilously between my fingers when I turn its dial. I find a set of cataract contact lenses, a pink wool suit that it is much too warm for, a false nose and a wedge-cut wig. I put them on in a McDonald’s bathroom, certain that no one will notice when I come out as this new and unremarkable person.

This, I know, is the familiar beginning of what’s possible; it is here in this bathroom stall, stretched across this mirror, in the back of a taxi or a stranger’s elevator that I have found a new kind of desert, an unplumbed humiliation. “I love you,” I whisper to myself in the mirror, my milky eyes suddenly looking somehow like yours. The wig has slipped luridly—it is too dark, too shiny, its falseness announcing something obscene, and I know that a careful stranger will recognize immediately that something is very very wrong with me, that something crucial is missing. “I love you,” I say to my reflection, and I want to recoil from myself, to split apart from this worst possible scenario, to run back to a self that we have both abandoned in our search for something more degrading. I notice that my eye is twitching again, a fluttering underneath the skin that suddenly means something else once it is framed behind the thick yellow lenses of a pair of glasses that I recently stole from an elderly woman who I sat next to at a free senior citizens’ lunch on 10th Street. I scare myself and turn my back to the mirror, remembering at once how it felt to belong to you.

It wasn’t hard to track you down after we’d both left the old apartment; your habits render you transparent, traceable. I waited for you outside of Sable’s on a Monday, my back turned to the door and my face down. I knew I’d found you when I heard the strange 4/5 meter of your steps, the drag of your left leg, the lope and the sway, the sound of your lighter catching when you stopped to light a cigarette. You didn’t recognize me, didn’t feel the pressure of my shadow when I followed you into the subway and then south to 30th Street; you had no idea that I was with you, that we were alone and together again. Your doorman is surprising lax; I don’t think he looked up from his paper for a minute, and I stood in the lobby and watched the elevator lights as they brought you to the 11th floor before I turned around and exited quickly, a departure that attracted nothing—a person who attracted nothing. “Don’t you miss me?” I thought, sending a message to you through the peal of church bells across the street. “Don’t you miss me at all?” But no response ever came from you, and I understood at once that I had to be content to have you from this distance, one-sided and far away.

The next time I came, I wore something special for you—I dressed as a teenage delivery boy, my arms weighed down with piles of plastic-wrapped dry cleaning, a stringy black wig hanging in front of dark eyes. “Morris,” I said to the negligent doorman. “1101,” he told me, again not troubling himself to glance up at me from his New York Post. I signed my real name in the book, I took the elevator to 1101, and I knocked on your door.

“I’m not expecting any dry cleaning,” you told me, and I heard what I knew must be a whore laughing from the depths of your apartment, the cackle and wheeze of a woman paid to fuck you. I wanted to threaten her with a gesture or a look, but you slammed the door in my face and disappeared. “Thank you, Sir, sorry,” I said, and I left the clothes in a heap on your doormat, meaningless garments that barely concealed a secret message from me to you: a silk dress that used to be mine.

“There is nothing wrong with it,” I told my mother. “It’s fine. The rooms are clean. My bed is clean.” I’d been living a kind of SRO existence in a hotel on Henry Street, hardly leaving my room except to go down the hall to the shared bathroom or to the front desk to request the hotplate. “I can’t help it, I worry for you,” my mother told me before I hung up the phone, after I’d dismissed her concern as hysterical and elderly, a worry that was both out of bounds and out of time. I didn’t tell her that I worried for myself too, that I spent my afternoons either staring out the window obsessing about what was to become of me or watching myself in a mirror I’d rested against a wall on the other side of the room.

I paid for the room with the money you’d given me. “Move on,” you’d said when you’d finally exhausted yourself of the pleasures to be found in my games and disguises. “You have got to find a way to sort yourself out…” In this case, sorting myself out meant day drinking, dressing out of my lockers at Port Authority, and following you from some kind of benign distance. The old woman outfits seemed to work best, and I noticed right away that I could sit close to you or trail you through a grocery store without attracting any of your attention. I slipped on some stairs once and watched you grimace and then move quickly away, unwilling to burden yourself with the responsibility of assisting a middle-aged woman who seemed to be suffering from some kind of grotesque skin disorder. “Help meeee,” I croaked, smiling when I watched your pace quicken and your body recede into the distance. A concerned hand brushed against my shoulder, a person unwittingly revealing the cruelty in her heart through this false and public demonstration of what she imagined to be compassion. “Don’t you fucking touch me,” I hissed at her, her face registering shock to see the red scales on my right arm lift back, revealing the smooth white of my skin beneath.

I felt that I was being watched as soon as I’d left the McDonald’s bathroom. “Caroline?” I heard a woman’s voice calling, and again “Caroline?” but this time closer and certainly directed at me. A hand touched my shoulder. I turned around to see a stranger in her mid 50s with a white bob and a printed dress. “Caroline!” She said again, her eyes fixed on my face and her hands gripping my shoulders. “What are you doing in New York? It’s been centuries! How are Bob and the kids?” Her false recognition alarmed me, frightened me in a way that I cannot adequately address, and I wrenched myself from her grip and ran, unconcerned when I felt the wig slipping from my head, not daring to look back as she shouted, “Caroline! It’s me! It’s Darcie McCall! From Fairbank! Your old neighbor from Fairbank!” I ran out of the bus terminal and immediately caught a cab, breathlessly telling the driver your address. “Your nose is loose,” he told me as we pulled away, and I reached up to feel the polyurethane skin of my prosthetic hanging slack from the right side of my face. I felt my cataract contact lenses drifting slowing over my iris, clouding my vision, I realized that the wig was gone, a flesh colored stocking secured tightly over my head.

I paid the driver and stumbled into your building, the doorman gazing at me quickly before saying your name and directing me to 1101. “Weird,” he murmured, returning to his paper. “I thought you was already up there.” I dragged myself to the elevator, suddenly aware that I’d somehow left a shoe in the taxi, seeing now that my foot was bleeding and leaving a smeared trail of blood across the tiled floor. I pushed the button and watched as the car descended.

I smelled my perfume immediately, heard my laugh and knew myself as soon as the doors opened. “Oops!” this counterfeit version of me said as she maneuvered around this new and abject model of myself. “Your nose is loose, Annie,” she told me, laughing and pushing past me, stopping and turning around when she reached the door. “It’s Cory,” she called to me. “From the agency,” and I watched the doors swing shut behind her, the sheen of my old silk dress amplified in the daylight and the volume of the skirt showing itself when she turned the corner. It was a perfect duplication, a perfect performance.

“Could you help me call a car please? I’m bleeding,” I told your doorman. “I’m going to Port Authority,” I whispered, trailing behind him and dragging myself towards your door. “What do you want with Port Authority?” he asked me, punching in the telephone number of a car service. “Yeah I need a car,” he told the receiver. “Name is…” “Caroline,” I told him, staring out the window and speaking in a barely audible whisper. “I need to get a bus, I’m going to someplace called Fairbank,” I said to both the doorman and myself, my fingers maneuvering over my face and pressing my nose back into place. “I have family there. ”

Editors Note: Though Toyen is referred to using she/her pronouns in this piece, we acknowledge that recent historical research has evidenced Toyen identified as male.

Toyen image credits: Cat. 57 Jindřich Štyrský (Ed.) “Erotická Revue [The Erotic Review].” Vol. 1 1930, Illustrations: Toyen 8 X 6 1/8 Inches (20.5 X 15.5 Cm); Cat. 61 Marquis De Sade “Justina [Justine]” 1932, Illustrations: Toyen. Prague: J. Štyrský (Edice 69) 7 7/8 X 5 1/8 Inches (20 X 13 Cm). Photos courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Sundblad images: All untitled, 2012, ink on paper, variable dimensions. Photos Courtesy Of Emily Sundblad.

This article originally appeared in Document’s Fall/Winter 2013 issue.