Best known as a fashion designer, Mizrahi thrives on immediate connection to a live audience—on the runway or the stage. Troy Chatterton sits down with the multi-hyphenate artist for Document's Fall/Winter 2012 issue.

I can’t stop thinking about a story Isaac told me from when he was a boy, impersonating Judy Garland, and performing for his friends. The way he told it all but said, See, my true calling. So when I asked if that performance felt right, he immediately countered, “Better than right.” That single story seems to hold the key to understanding Isaac’s extraordinary journey.

But I’m getting a little ahead of myself. It was late June, and I was sitting in an old wooden chair, in the attic bedroom of a converted barn in Bridgehampton, looking out the window onto Arcadia. Nothing about this scene would tip you off that I was minutes away from calling Isaac Mizrahi to talk about his new cabaret this fall at the Laurie Beechman Theater—a small club in the basement of the West Bank Café on 42nd Street.

Nervous? You bet. Excited too. We had never spoken, and quite frankly I wasn’t sure I could keep up. I had my opening line ready. I had specific questions to ask, and themes to discuss. I had Susan Sontag’s essays swimming in my head.

“Isaac wasn’t concerned with putting me at ease during our conversation, but his enthusiasm and intimate way of conversing had that effect. His voice was familiar, as if talking to an old friend.”

I even had an old story tucked in my back pocket, if necessary. I wanted Isaac to know that I’d experienced a cabaret of the highest order. I was fully prepared to tell him about the time I sat front row at the Café Carlyle, and how Eartha Kitt had tempted me, down right dared me to touch her leg. But I wouldn’t. Eartha’s singing and seduction continued, so finally I reached out, only to have her snap her leg away and hiss, “Don’t touch what you can’t handle!” The story stayed in my back pocket.

Cabaret is a specific art form and Stephen Holden, the cabaret critic at The New York Times brilliantly defines it: “The peak cabaret experience is a three-way relationship among singer, song and audience in which performers pour their life experiences in thematic shows using the American songbook as a platform; songs are stations in an autobiographical journey shared with the listener.” So you see, speaking with Isaac about his cabaret gives license to talk with him about his personal life.

Isaac wasn’t concerned with putting me at ease during our conversation, but his enthusiasm and intimate way of conversing had that effect. His voice was familiar, as if talking to an old friend. Of course this wasn’t true, but having watched the documentary Unzipped, and seeing him over the years on TV, gave a sense of comfort. By the time we were 20 minutes into the conversation Isaac began calling me “darling,” and I was relaxed enough to go after the things I really wanted to know.

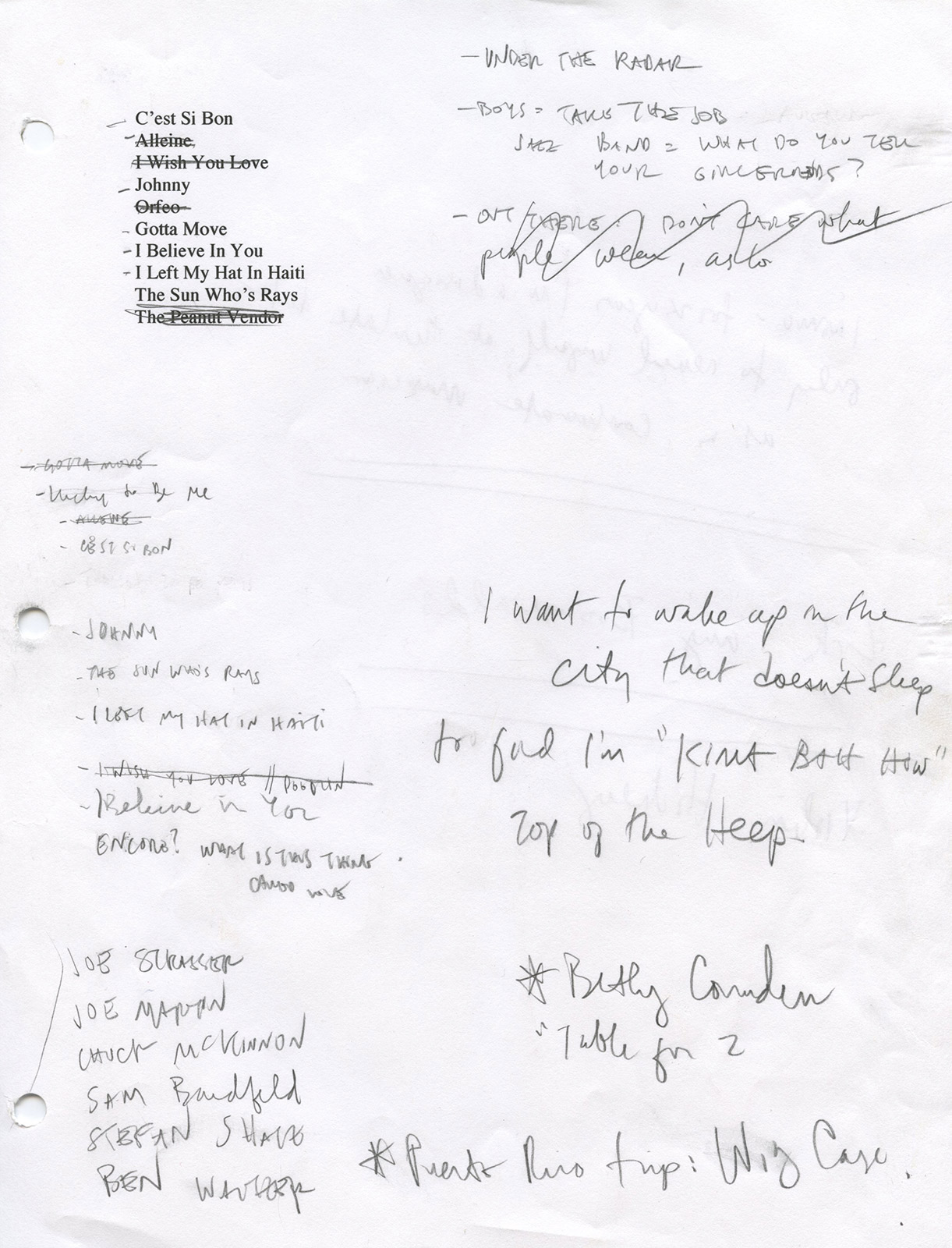

The question that most intrigued me was why, with all the many projects he’s involved with, is this show important to do? But first, I wanted to know what was on Isaac’s mind and what the themes of this new show would be. Aging for one thing. Isaac wants to share the fabulous and not-so-fabulous realities of being 50 years old. Another theme of the new show will be public appearances versus private thoughts. What people see and what is going on within are two di erent things, and Isaac believes we’ll be very surprised by what he’s really thinking. Being able to articulate private thoughts and say what most people won’t is a common trait with all the greats of cabaret. Think Patti LuPone, Sandra Bernhard and Justin Vivian Bond. I mention these three performers because they each came up in our conversation and he’s in awe of their conviction to “really give it.”

But is Isaac ready to really give it? Is he willing to get personal? He’s a married man now. A newlywed. Last December he and Arnold Germer were married at the New York City Clerk’s Office. I wasn’t sure he’d even want to talk about his love life, so I was surprised by his openness and willingness to discuss his wedding day. I asked if anything about the experience of getting married surprised him, and he replied that by the time the couple had navigated all the many windows at City Hall and stood before the offciant ready to proclaim their vows, he burst into tears. What surprised him, was the emotion built up, waiting for release, proving how deeply getting married mattered. Isaac told me this story with his trademark humor, tenderness and intimacy—a recipe for cabaret magic.

Towards the end of our conversation, I risked telling Isaac about the discussion I had with my editors regarding his portrait. They wanted, “Less camp, more chic.” That phrase got under my skin, and I wondered why we’d want a portrait of Isaac that didn’t capture his intrinsic sensibility. Or, did I completely misunderstand camp? I went to the source on this subject—Susan Sontag—and read her essay, “Notes on Camp.”

“Why a cabaret now?… The answer seems to be that cabaret is the one art uniting all the creative threads that allow Isaac to express himself in a way that feels the most authentic.”

Isaac was amused, not offended, because he understood camp as being a compliment and it opened up a fascinating conversation about camp of old—Martha Graham, Liberace and new expressions of camp, the choreographer Alexei Ratmansky’s “Firebird” and the TV series “Glee.”

Susan Sontag defines camp in 58 notes in her famous essay, stating that camp is the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theater. Camp, she writes, is also the attempt to do something extraordinary. I read No. 56 to Isaac: “Camp is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes, rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of character.” “That’s lovely,” he said.

So why a cabaret now? He’s a fashion designer, costume designer for theater and dance, an actor, a writer, a director and a TV personality. The answer seems to be that cabaret is the one art uniting all the creative threads that allow Isaac to express himself in a way that feels the most authentic. At the core, he is a communicator, a storyteller, an entertainer; he seems to thrive on immediate connection to a live audience. I’d go so far as to say that cabaret may be more important than all his other artistic expressions.

After our conversation I was left with a sense that he is a man at an unexpected place in life that even he could not imagine. With all the possibilities that his life affords, he is choosing to step back on stage, not as Judy Garland, but as himself, Isaac Mizrahi, and share his life experiences because it feels right, or maybe, “Better than right.”