The photographer’s recent project asks how architecture shapes reality in an era of mass tourism and simulation

The eternal city, the city of sin—one viewed as fixed for centuries, the other constantly being built, dismantled, and rebuilt. Each with their graveyards: of millenia-old societies, of outmoded neon signs. Rome and Las Vegas might form opposites in the everyday imaginary, but might they have more in common than the mere simulations of the Italian capital dotting the Strip?

For Dutch photographer Iwan Baan, looking at both cities at once allows insight into how people interact with architecture and how architecture acts on people in a world where built environments are becoming increasingly similar and increasingly mediated by touristic and image-based expectations.

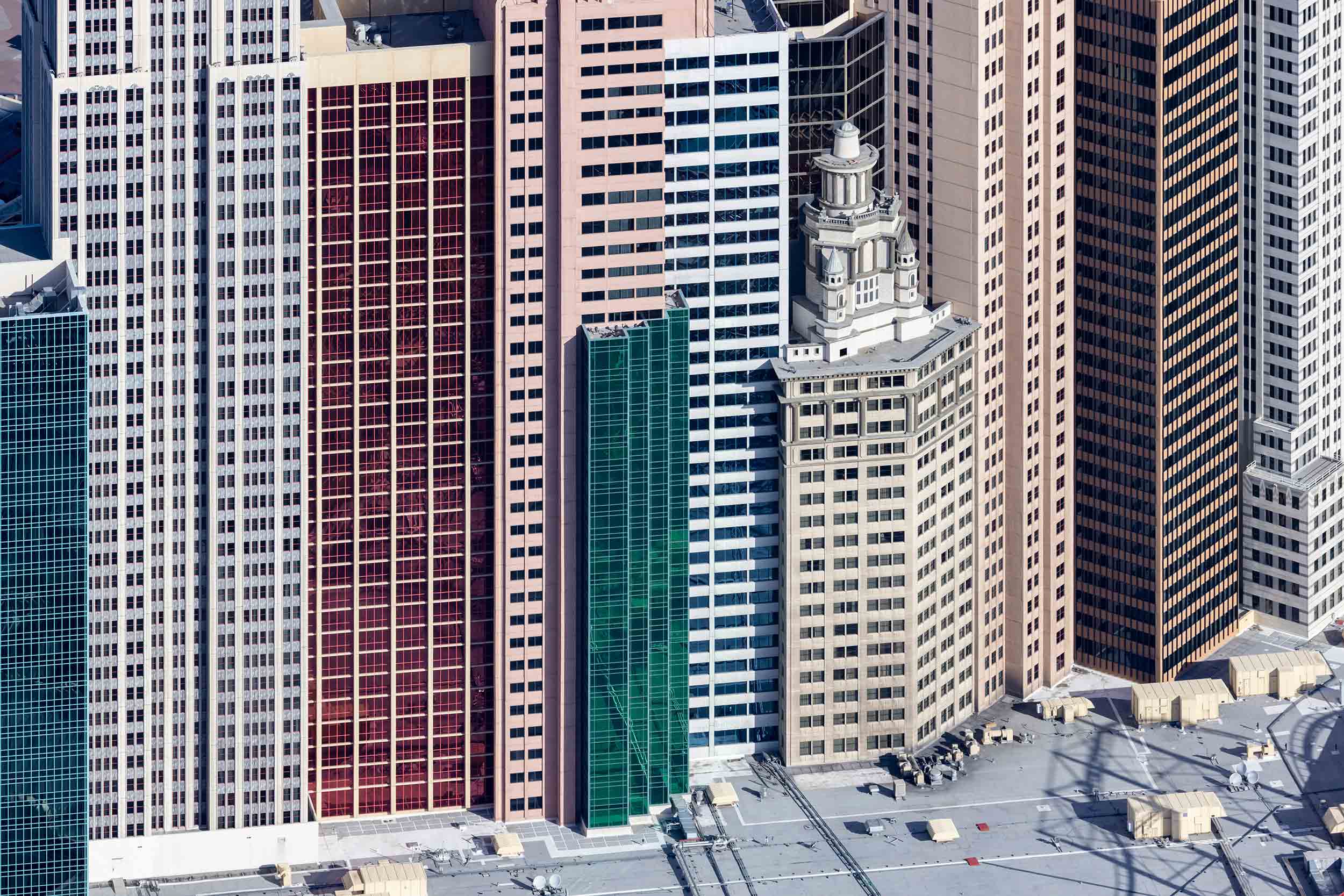

In his book Rome — Las Vegas: Bread and Circuses, published last year by Lars Müller, photographs of both cities intermingle. Shot from helicopters above (Baan is renowned for his aerial shots of buildings and cities) and on the ground, the images conflate these famous environments while also revealing the unseen and ignored: the bland concrete that glitzy facades get attached to, the parking lots, the housing workers likely live in.

Rome — Las Vegas offers a renewed viewpoint on these well-documented locations. Baan’s photos are accompanied by essays by Ryan Scavnicky and Lindsay Harris, as well as a transcription of a visit by Baan and Izzy Kornblatt to the house of the legendary architect and theorist Denise Scott Brown, who with Robert Venturi and Steven Izenour co-authored the seminal book Learning from Las Vegas in 1972.

The object is not a typical perfect-bound book. The paper is stacked, meaning images end up bisected and mixed up, running front-to-back. The cover and dividing pages are gold and reflective. It’s closer in height and width to a standard hard-back novel than an artbook, yet it’s seemingly overflowing with images. Shiny, disorienting, and pushing its own boundaries, Rome — Las Vegas distills both cities.

But in the era of The Sphere—the 367-foot-tall orb-shaped screen-slash-building in Vegas—and in a time when millions upon millions of snapshots of Rome have been made since the dawn of photography, what does documentation mean for the material cities Baan visits? In Rome — Las Vegas reality and fantasy are not always so distinct. But as a physical, tactile object that reveals the structures that undergird these cities, as well as the people who traverse it, we are reminded that even simulation has a substrate; we’ll see it if we look closely.

“At some point you feel like it doesn’t matter where you are. Like, would this all happen inside The Sphere or your VR goggles?”

Drew Zeiba: The first time I ever went to Rome, I took the train from Florence, and I was like, This countryside looks like New Jersey. Then I was like, Wait, it’s actually the opposite. But then the more I spent time in Rome, the more I experienced this reverse Stendhal syndrome. Compared to Florence, Rome and especially the Vatican are so tacky, and you can really feel this performance of a false continuity of the Romans looking to the Greeks, the Renaissance artists looking to the Ancient Romans, 18th-century architects looking back to the Renaissance, and on. The comparison to Las Vegas was natural for me. But I’m wondering what drove you to want to create this comparison or this togetherness? How did the project come about?

Iwan Baan: Like a lot of my projects, it happened by coincidence. I’ve been fascinated by Las Vegas for a long time, just the absurdity of the whole place and what photographic chaos it can be. There’s so much to see, so many impressions all the time, which far exceed my comprehension.

I’d never found a good project to do there, but then two years ago I was passing through and I got this call out of the blue from the curator at the American Academy in Rome asking if I had a project that I could show there. They warned me that Italians love to see Italy and that it should have an Italian subject. And I said, ‘Sorry, I don’t have anything in Italy, really, but I’m standing here in front of Caesar’s Palace, which is as Italian as one can get outside of Italy. Should we do something with that fact?’ We were talking and realized that it was 50 years since Learning from Las Vegas was published, which was a project that also began at the American Academy. We thought, Let’s take a new look at these two cities, Las Vegas and Rome.

It became this whole story about mass tourism, this sort of incredible boredom in these kinds of places, and how people need constant entertainment and influx from outside. And about how similar all these worlds are starting to feel everywhere. In my travels, I often wake up and barely know where I am. Even in these iconic places, you get this similar feeling that worlds seem to merge.

Drew: I almost wanted to say the degree of simulation in Vegas makes it somehow more specific, but then just an hour ago, flipping through the book again, I had to do a double take because of the reflection of the Chrysler Building facsimile at New York-New York. I see the original all the time, and at first I experienced recognition, but then disorientation because the context seemed all wrong. It’s very uncanny.

Iwan: Everything is so thin and everything is so compressed. In the sort of centerfold of the book where you have that aerial of the whole Strip where it’s all these facades and things which are recognizable but completely out of context. They’re just like, boom, boom, boom, on top of each other, and then on top of that you now have The Sphere, which is an icon that can be anything. You can be anywhere. It really doesn’t matter anymore what it is, or where you are. The whole thing becomes this computer simulation.

Drew: Thinking about thinness and being able to see the facade application or the compression that happens from the aerial view, I was wondering about how you were thinking about the relationship of the aerial shots with the shots that are ground level. What are you trying to capture between moving between those two modes, the human-eye and bird’s eye views, for lack of a better analogy?

Iwan: For me, it’s always important that there are these very personal moments and characters on the street you run into who you have no idea what they’re doing. They’re all in their own world, sometimes in these completely bleak situations. And the backside of Las Vegas is incredible. Everything is just a facade, so when you step behind that facade you see the infrastructure—the parking lots, places where people are lost. And then in moments where I’ve used these wide shots, you can see the context and how it is all crushed together.

These aerial shots are always revealing how this world operates and comes together, and then they’re meeting these very personal moments of characters and people who make up that place. All these locations also attract really specific people, which I find fascinating. You come into the gardens at the Bellagio with these totally oversized flowers and then it’s only old ladies with flower dresses arriving there.

“That’s something I try to show in my photographs, from these personal moments to these large contextual ones. They tell the story of the city and the place and why it’s there and not somewhere else.”

Drew: I love that photo of a person wearing pink feather wings standing face-forward in a niche or corner or something. It’s so fun and mysterious.

You’ve discussed how compared to Vegas, which has essentially been built and rebuilt, Rome’s city fabric has undergone less change in its recent history. But Ryan Scavnicky’s essay in the book, ‘Bread and Circuses,’ discusses how all these places have essentially become sites for people to take their own photos—whether of themselves or of things around them—and to increasingly relate to these locations through the mediation of that location. He uses the example of Google reviews. Coming in as a photographer, how do you approach these sites, like the Trevi or Bellagio fountains, that have been photographed by so many people for so long, in both art or tourist contexts? What tactics do you use to approach cities that are, at times, already so over-determined by their images?

Iwan: It’s also very much about focusing on these characters in these sites. This book became a story on mass tourism and how all these people anywhere in the world are trying to find that moment where they look their best and they have these new experiences, and so on.

You come to these centuries-old places, like the Vatican, where there are these food and beverage courts, which look exactly the same as those anywhere else in the airport or Las Vegas. And it has huge floor-to-ceiling prints of the gardens outside, but then people are just stuffed there in the basement. At some point you feel like it doesn’t matter where you are. Like, would this all happen inside The Sphere or your VR goggles?

Drew: By going behind things, going places you aren’t ‘supposed’ to be, or going up in the air, there’s an aspect to showing the ways buildings might not be unique in their construction—you’re deflating how they’d like to announce themselves as images. But you’re also showing, as you said, a backside or underbelly. We understand how people, workers, and objects move through space. You’re showing unhoused people, people passed out, tract housing on the Strip’s fringes, and so on. So at the same time as you have these specific characters, you’re also revealing the systems they’re within. It’s very distinct from a type of photography focused on architectural monumentality or something.

Iwan: It’s the same way I approach my commissions for architects. It’s the same zooming in and zooming out from these very personal moments. With very specific architecture, people behave in a different way and experience it in a new way. That’s something I try to show in my photographs, from these personal moments to these large contextual ones. They tell the story of the city and the place and why it’s there and not somewhere else. And that’s what I find interesting in these kinds of places—sometimes it doesn’t really matter. And if you think about all these unique and existential places but then you look at the Trevi Fountain, it’s actually almost the same veneer [as buildings in Las Vegas] of a facade kind of placed against another facade—and we all think, That’s real, that’s the real deal. People have been doing that for a long time.

Drew: I wanted to ask about the design of the book. One aspect that stood out is the binding. You’ve used staples, which normally is a kind of cheap binding, but it’s this really thick book so it’s clearly actually custom and creates this interesting and highly specific shape.

Iwan: It was based on the classic manga strips. And, indeed, it should, should have been the cheapest binding. But of course, nowadays, no one does it so it’s the most complicated thing. I made a small edition for myself which was basically held together by an elastic band and you could really take the pages out, and see how they run front to back, but the publisher was a little bit afraid of a stack of papers in a bookstore.

Drew: This comes in part from how the paper runs through, as you were discussing, rather than being folded as signatures, but there is so much texture between the paper types and it’s often so reflective. It’s very visceral.

Iwan: It’s, of course, all also very much inspired by Las Vegas and this glitz and glamor. You constantly move back and forth between these two worlds. We start with a mix of Rome and Las Vegas. Then you have Rome to Las Vegas. You go back to Rome, and then you have that mix again. And then we visited Denise Scott Brown, which was a very interesting visit, where you step into this time capsule from a life which is all centered around that seminal book, and you’re having lunch there with her and the plates were Las Vegas plates.

Drew: The last design element I wanted to ask about are the page numbers. There aren’t any. It’s like how there are never windows in a casino.

Iwan: There are no page numbers and no captions. I wanted the viewer to be lost in these worlds—at some point you don’t know where you are. That’s the experience I had wandering back and forth between these two places.