Document spoke with 7 recent graduates on what drives them to live, work, and create in the Japanese capital

Tokyo is a city that knows how to dress. Walk down the street in a bustling neighborhood like Shibuya or Harajuku, and you’re bound to discover a trend born from the labyrinthine capital. Time and again, the sprawling metropolis proves itself to be an incubator for sartorial creativity.

Unsurprisingly, the city boasts a wealth of notable design programs—and to get a sense of new horizons, Document caught up with fresh graduates from the Me School, Coconogacco, and Bunker Fashion College. Different themes arose in conversation, indicative of each designer’s unique perspective.

Seiya Sawada, for instance, envisions utopias that call back to nature, while Hiromi Murao channels a virtual realm that challenges the notion of ideal body types. If there is a common denominator, however, it’s a penchant for iconoclasm: These six young designers are questioning established norms and accepted truths, both in Japanese society and in global fashion at large.

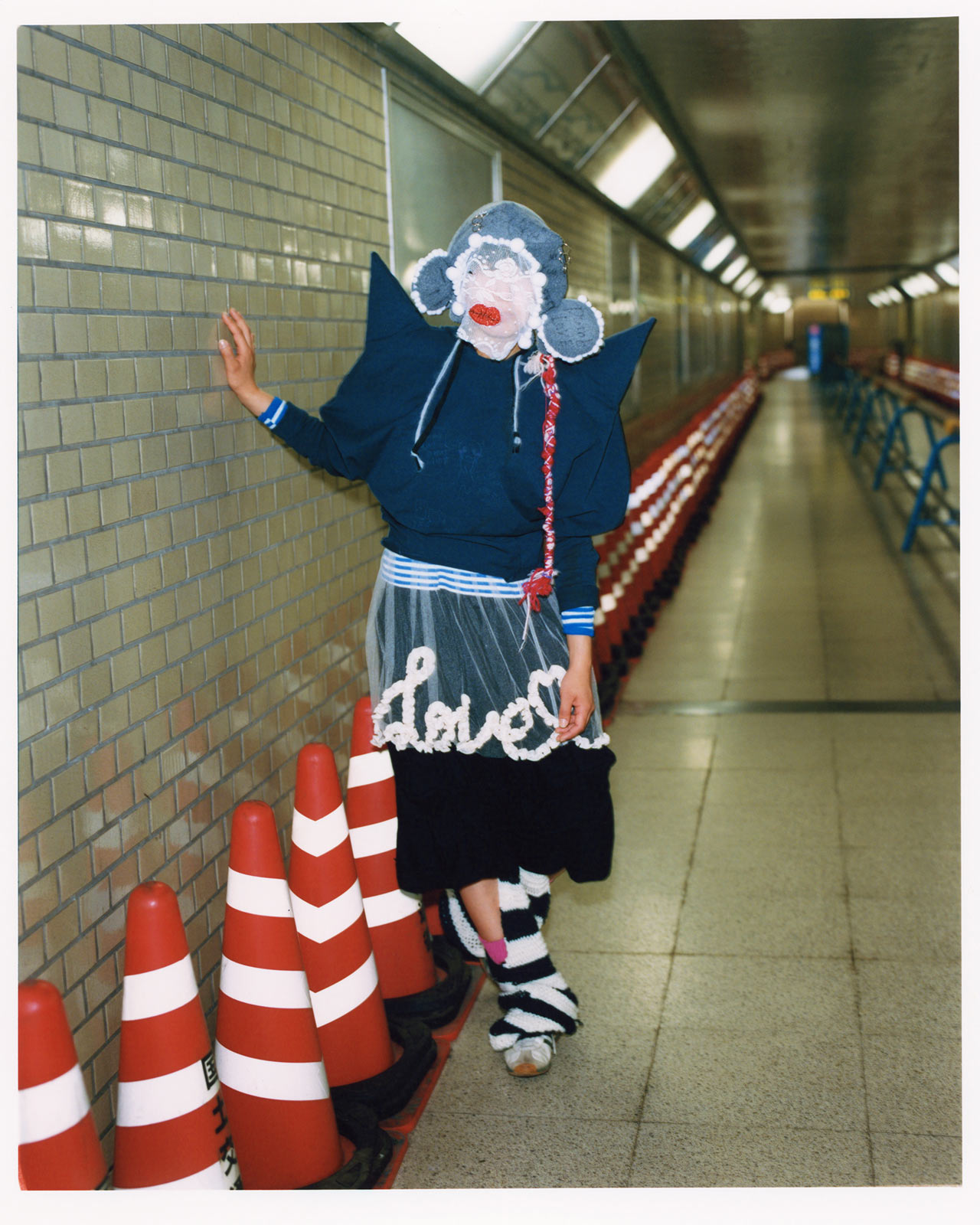

DEADLY SWEET

Document Journal: Thematically and materially, how would you sum up your collection?

DEADLY SWEET: It revolves around visually expressing emotions. I’ve been working on creating masks because I struggle with verbal communication, and I’ve been producing pieces that convey emotions without relying on words for a long time. This collection holds great significance to me personally, and I hope it can also serve as a source of solace for others.

In terms of material selection, I’ve been meticulous about choosing gentle fabrics to avoid excessive sensory stimulation in everyday life. I’ve also focused on providing a comforting tactile experience in the details.

Document: How long have you known your passion for design?

DEADLY SWEET: The origin of my passion for design dates back to my elementary school days when I received a Licca-chan doll. At one point, I wasn’t satisfied with the available clothing options, so I took pink felt and a needle that my mother gave me and created multiple outfits by myself. I had no knowledge, but the sense of achievement from making something was overwhelming.

From high school to the present, my passion for design has only grown stronger. I consistently carry paper and a pen with me, and I devote more time to contemplating creativity than scrolling through social media.

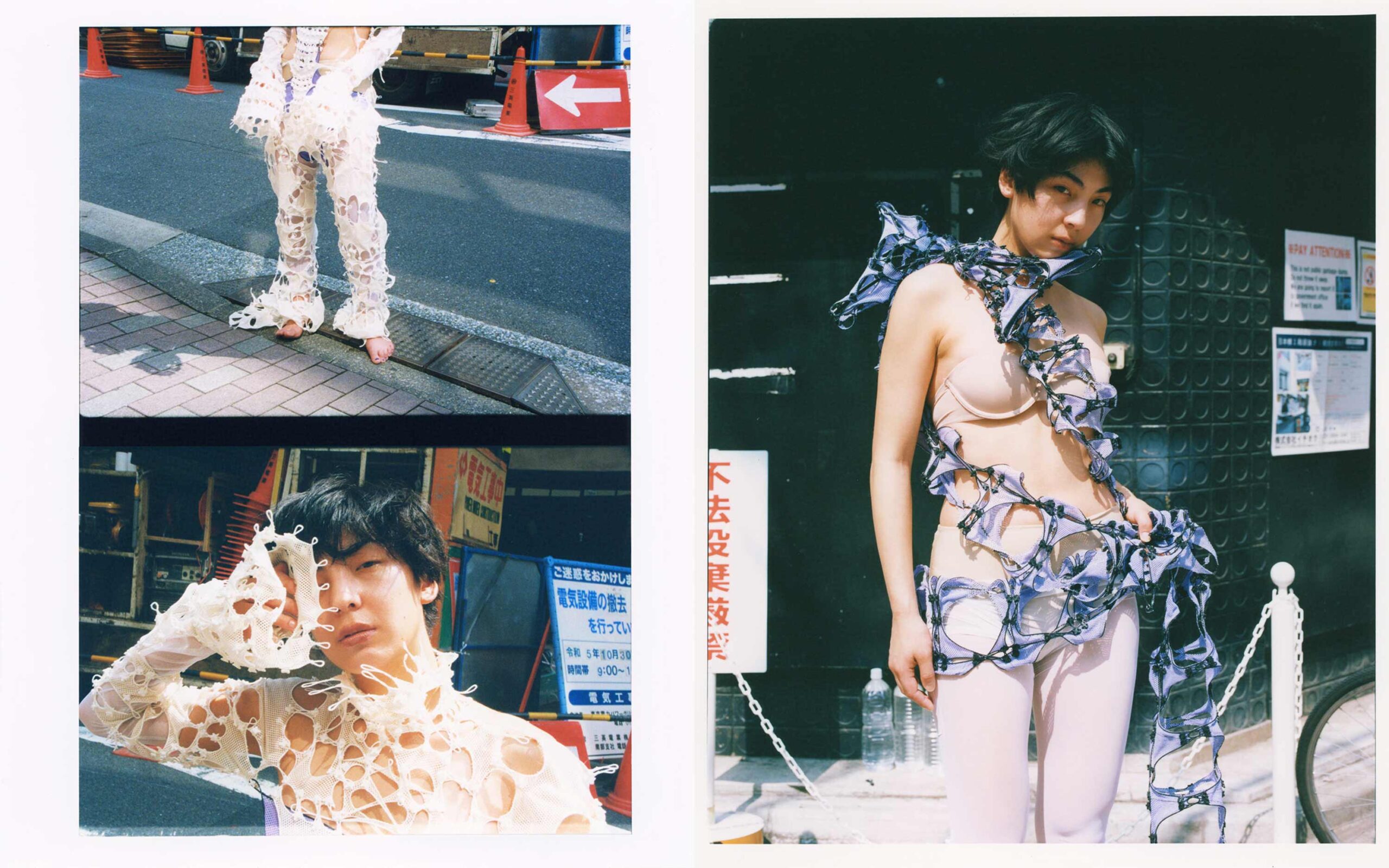

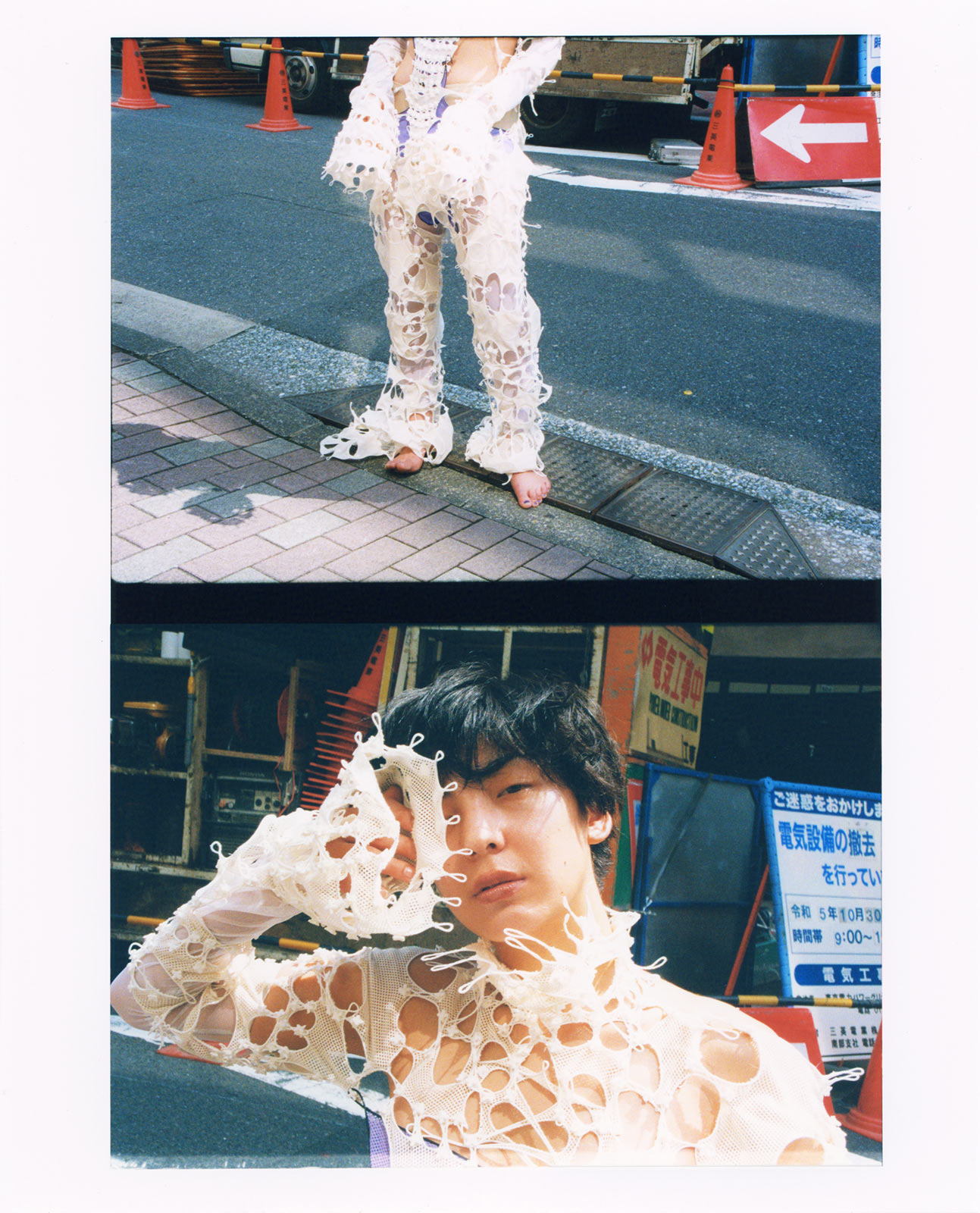

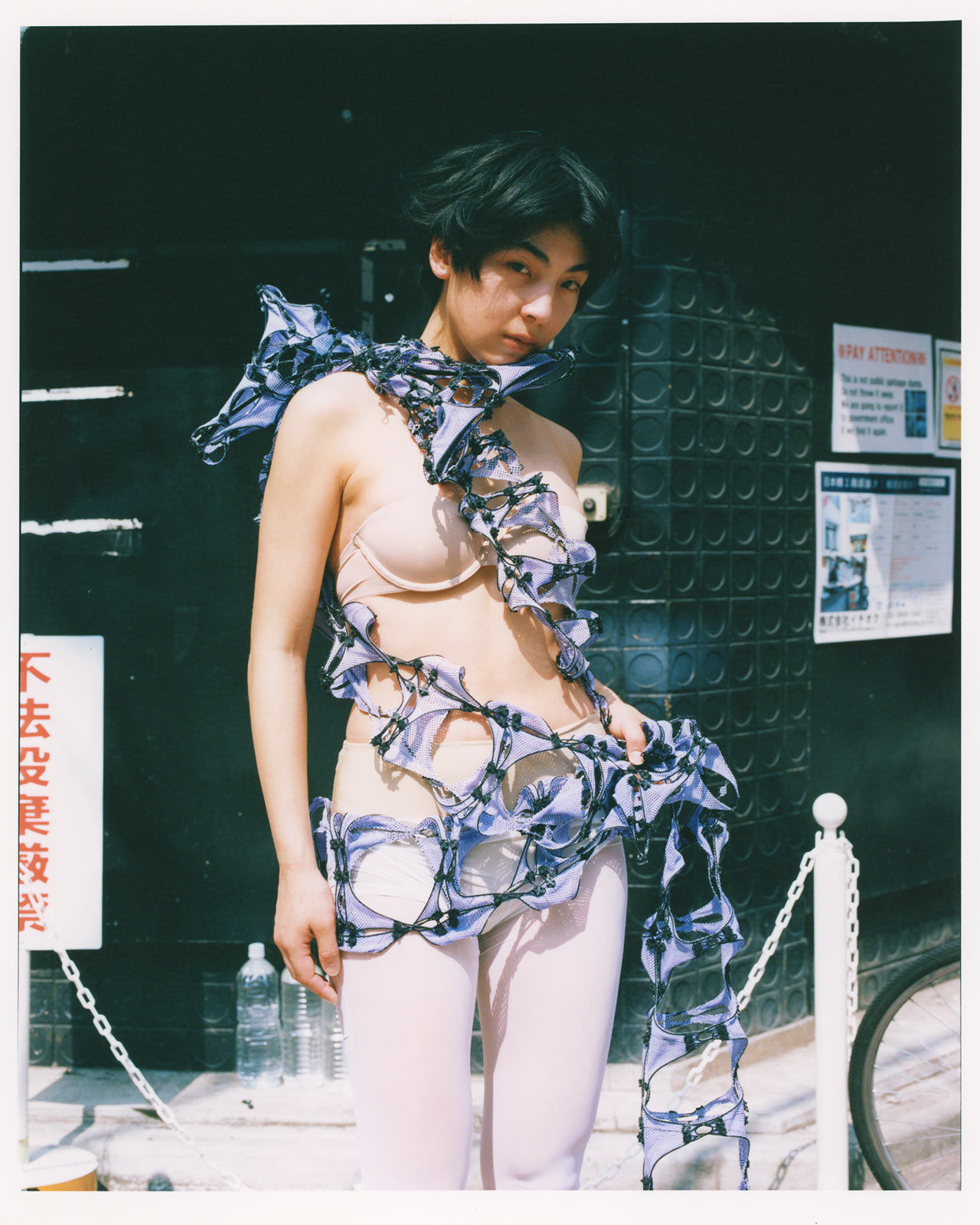

Hiromi Murao

Document Journal: Thematically and materially, how would you sum up your collection?

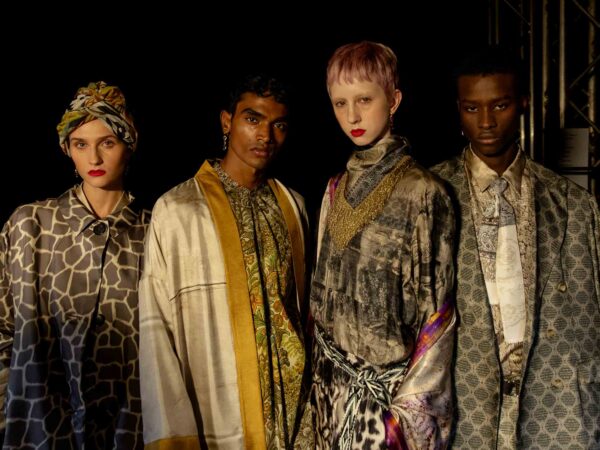

Hiromi Murao: The theme is Virtual Paradise. I use three-dimensional computer graphics for design and printing. Sculpting from an ideal body, and making clothes to fit that shape, feels like a virtual act. However, clothing has potential because it can influence people who live in the real world.

Document: What type of person do you design for, and how do you hope your clothing will make them feel?

Hiromi: I am targeting men who have a body that is not the [traditional masculine standard], and people who share in this sense of beauty. I want to create an atmosphere of openness. I want society to welcome the new masculine image when they see people wear [my designs].

Taisuke Toya

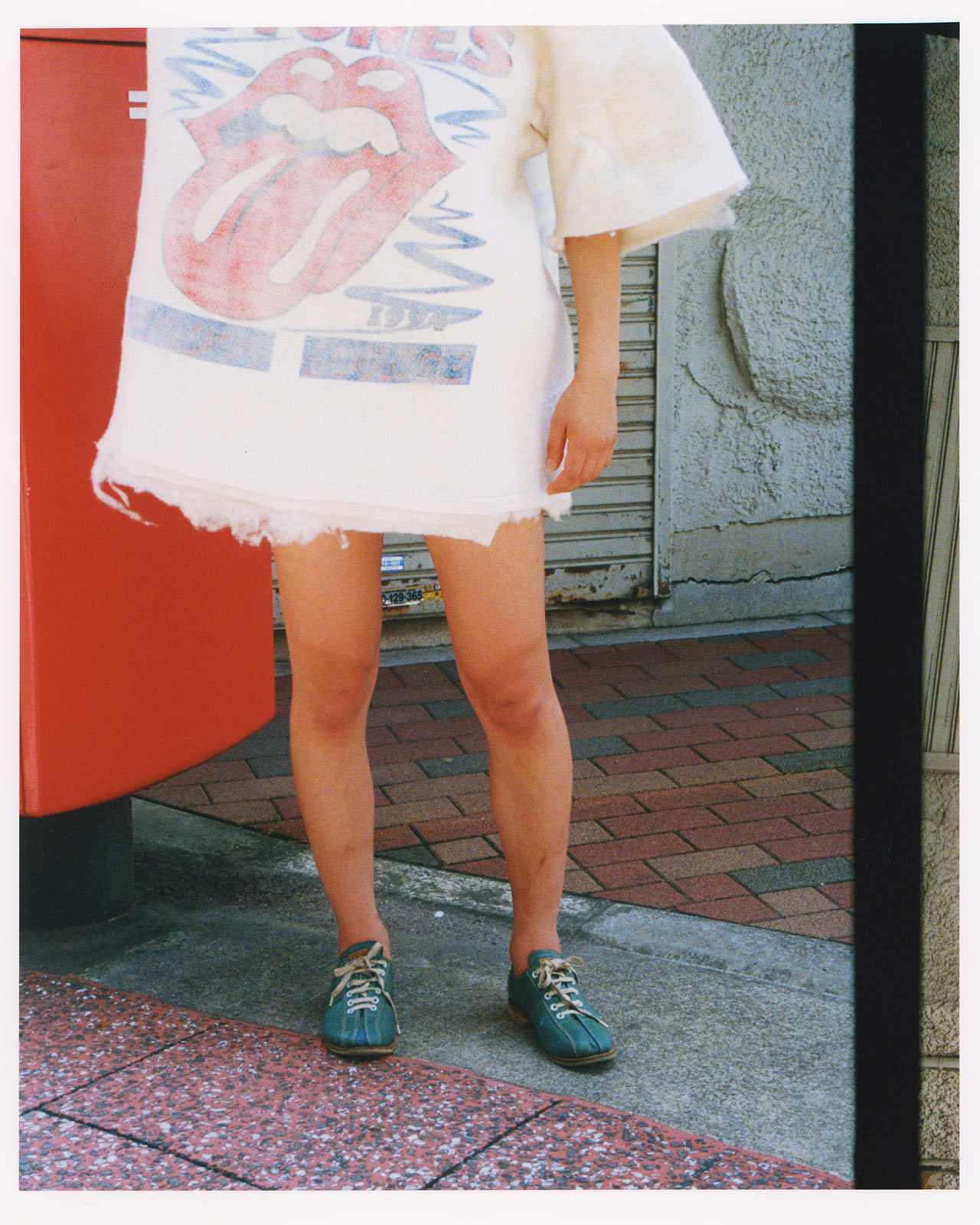

Document: Thematically and materially, how would you sum up your collection?

Taisuke Toya: My work is based on the theme of urbanity and the consumerist nature of fashion. The economic activities woven by the human race [in this] era have influenced the strata of fashion. In Japan, 1,600 tons of clothing are incinerated every day, which is a major [contributor to] environmental problems. Many people in the fashion industry in Japan are blind, unthinking, and pretending not to see what is happening. It is necessary to present a new way of consumption, cycle, and supply chain.

Document: How does the city of Tokyo color your work? What defines it aesthetically?

Taisuke: Tokyo is seamlessly organized, with symbols of consumption, buildings, and people. I feel that people who live in closed urban space lose their individuality. I aim to evoke the reality of the self by transforming liminal spaces that emerge in everyday life into works of art.

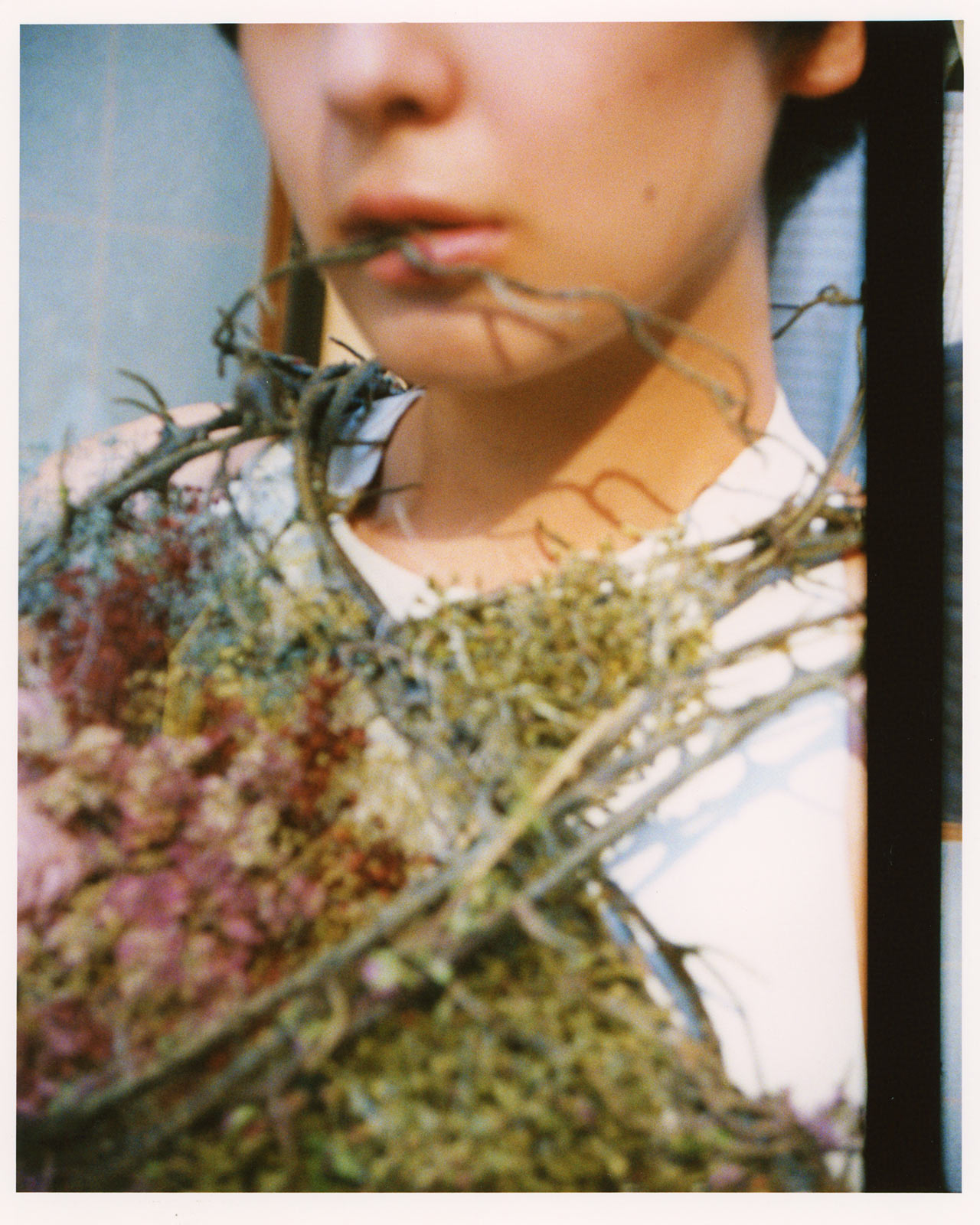

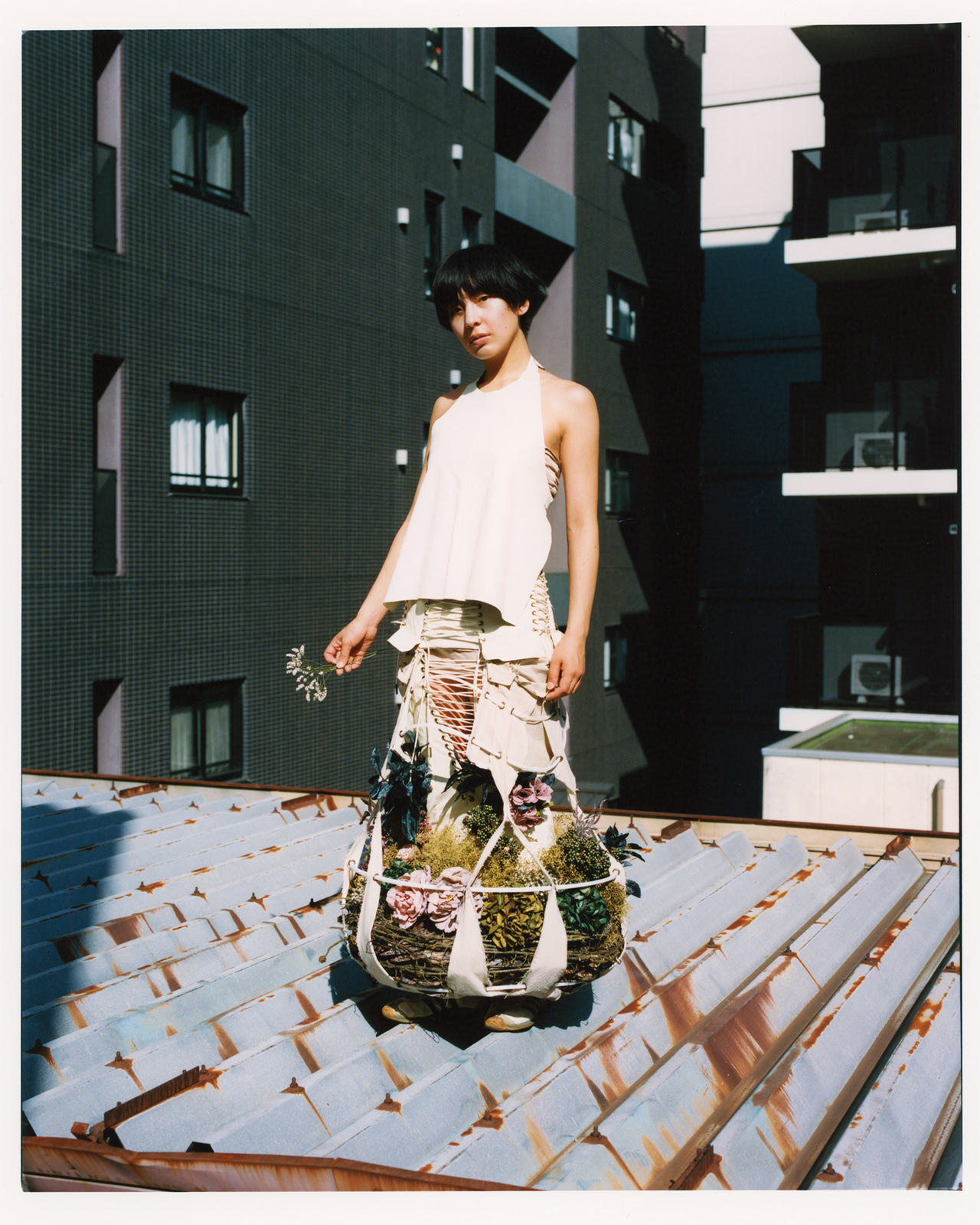

Seiya Sawada

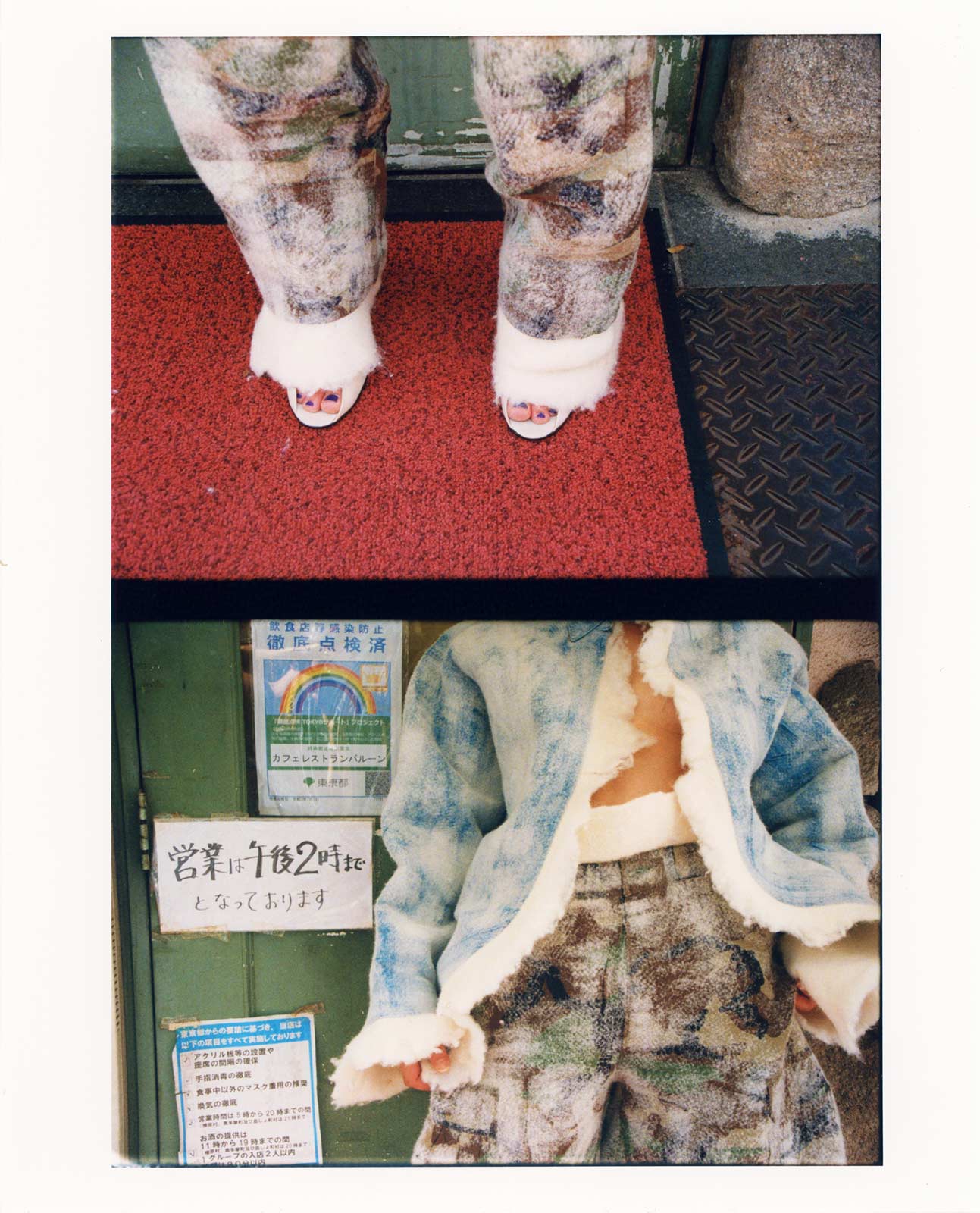

Document: Thematically and materially, how would you sum up your collection?

Seiya Sawada: The theme of this work is Utopia. Canvas expresses blankness, and the plants express human sexuality. The thorns wrapped around mean that pain does not always cause agony.

Document: How long have you known your passion for design?

Seiya: Since I was little, I liked clothes, and [eventually, I enrolled] at Bunka Fashion College. I soon became skeptical of Japanese fashion and society, and I quit. After that, I wanted to pursue the meaning of connection between people—and now, I have come to this point.

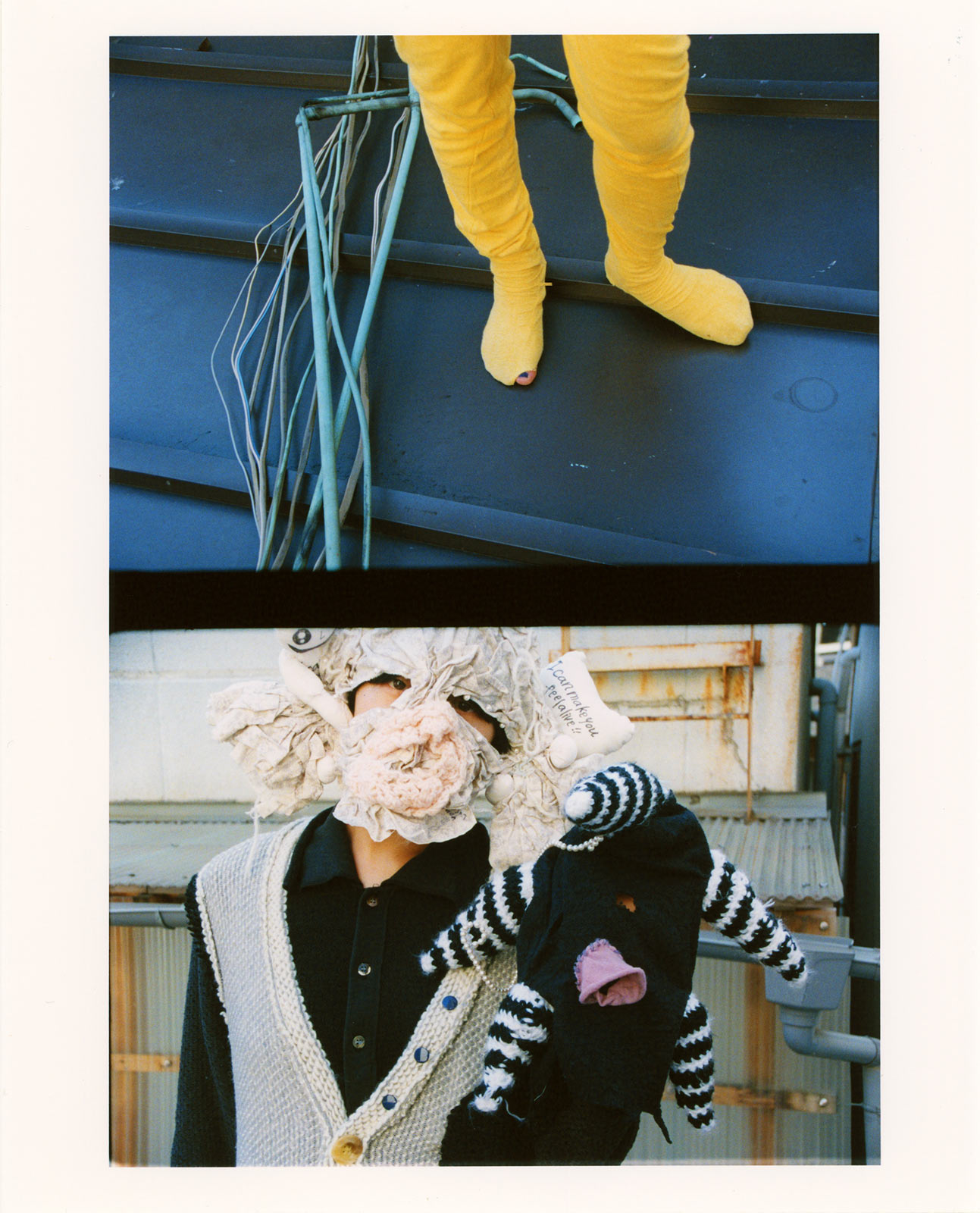

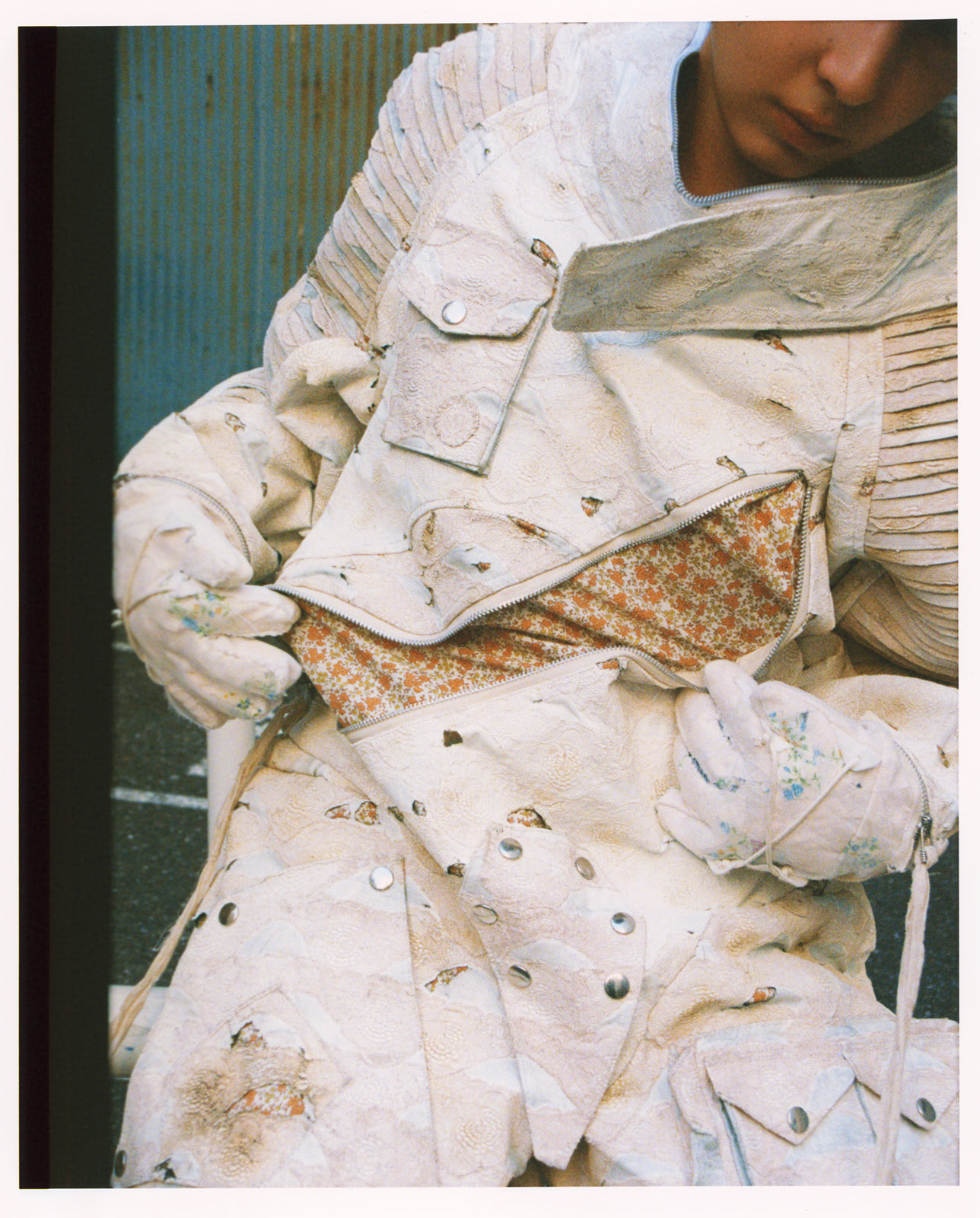

Tomohiro Shibuki

Document: Thematically and materially, how would you sum up your collection?

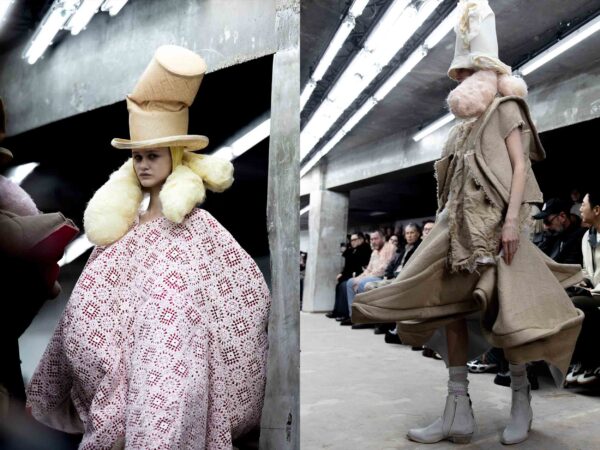

Tomohiro Shibuki: The theme is ambiguity. In fashion, clothes’ significance [lies in] how they can be differentiated from others. I am trying to create a harmony by flattening each feature and abstracting it.

Document: What of your work are you most proud of?

Tomohiro: My work is made by wrapping existing old clothes with felt. The purpose is to connect—leaving the individuality of the clothes, containing them without erasing them. I’m glad that I was able to express that I can create harmony, even with things that are usually incompatible.

Masashi Kani

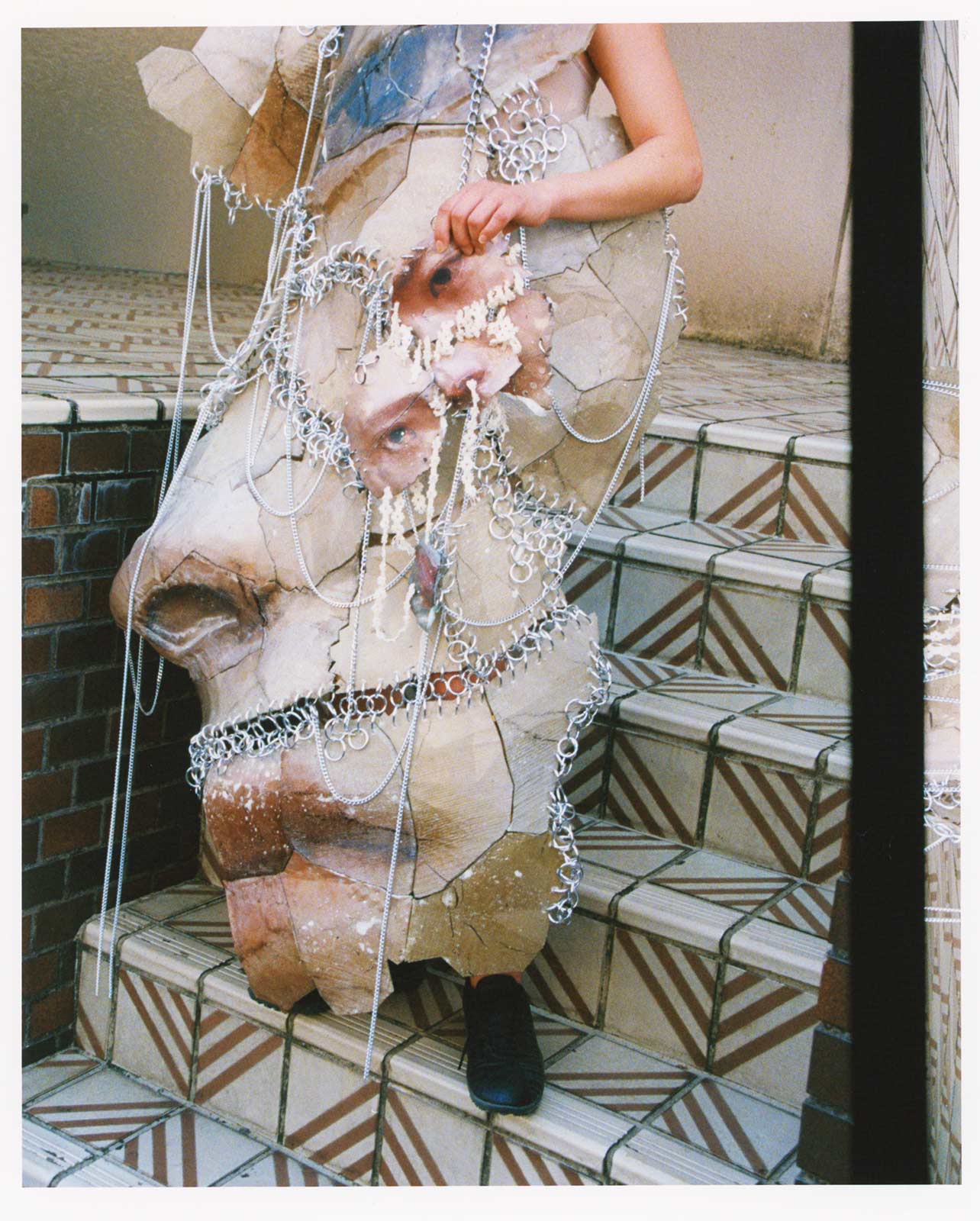

Document: Thematically and materially, how would you sum up your collection?

Masashi Kani: I scanned my own face and printed it out in 3D. In the past, I tended to stay in my room and kept my mind balanced by living as an alter ego—an avatar—in virtual space. However, I felt that it was important to live in reality. The feelings and scenes of those days are my inspiration.

Document: What type of person do you design for, and how do you hope your clothing will make them feel?

Masashi: My ideal is to make clothes that accompany a person’s life. That’s why we [strive to] make [distinctly] wearable clothes.

Jaesun Park

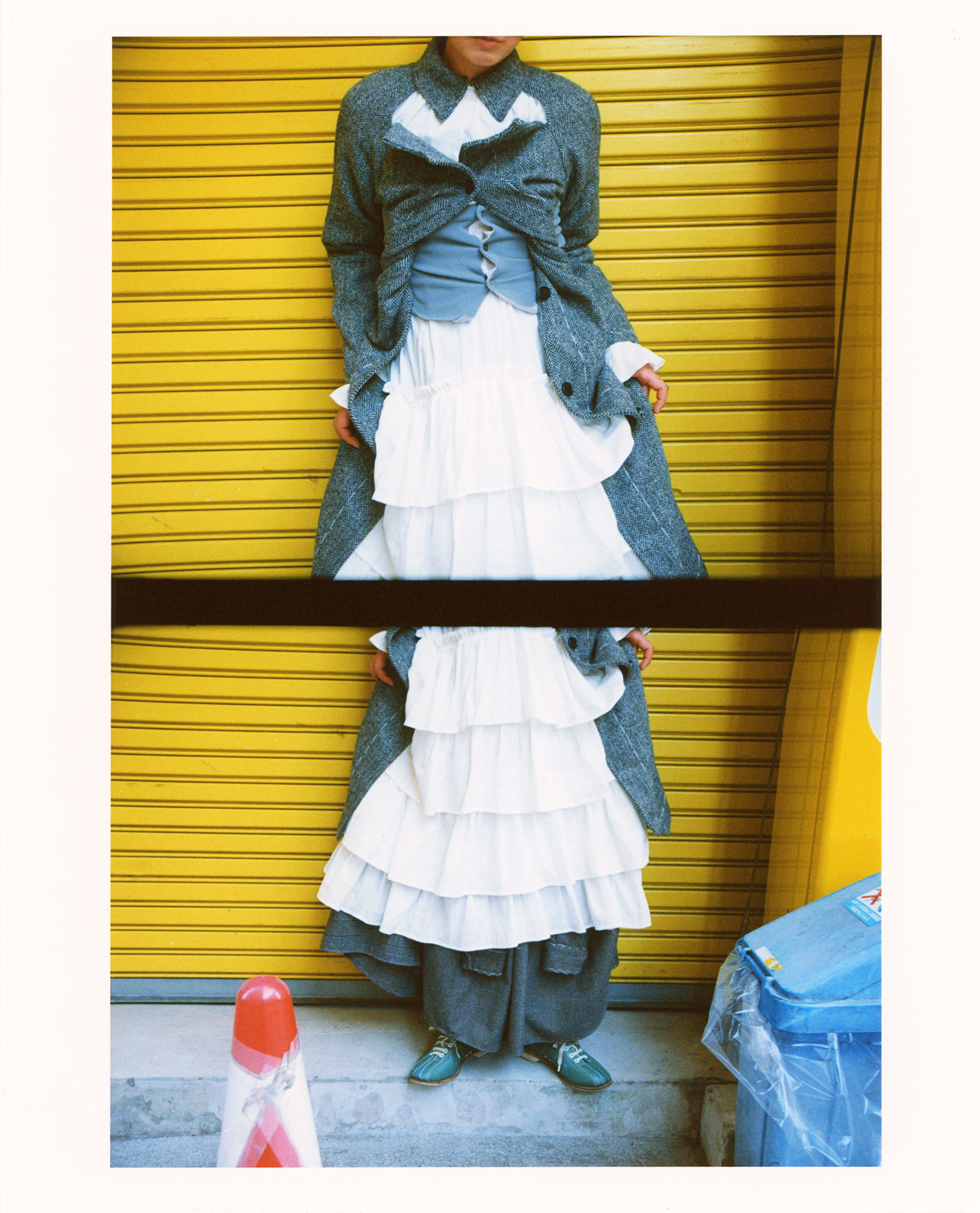

Document: Thematically and materially, how would you sum up your collection?

Jaesun Park: I made tailoring the big theme of the collection. Rather than developing new materials, I focused on how to customize couture for women with traditional men’s clothing items—like I’m a tailor. Traditional men’s clothing is reborn as couture for women through draping and cutting; I changed the pattern so that various styles could be possible with one piece of clothing.

Document: What’s next for you?

Jaesun: I am currently working as a model in Tokyo. There is something I felt while working: Japan values the quality of its products, thinking deeply and going through various trials and errors. I want to emulate this Japanese spirit. And I want to go to the wider world someday and [offer] my collection.

Model Mei. Hair and Make-up Saki Kojima. Special thanks to coconogacco, Kagam.