Now beloved by the industry she once aimed to disrupt, the fashion maverick will be remembered for a life spent questioning the status quo

Vivienne Westwood passed away on December 29, leaving an indelible mark not only on the fashion world, but also on culture at large. Known for translating punk’s irreverent, anti-establishment attitude into the visual language of couture, Westwood’s reputation as a maverick was cemented by her own well-documented rebellious streak: From impersonating Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher on the cover of Tatler, to meeting the Queen with no panties on, to the controversial political slogans often printed on her t-shirts. Westwood’s formidable influence (and personality) has since been memorialized in comments from public figures ranging from Paul McCartney to Annie Lennox, who described her as a “fearless, formidable force of nature who turned everything upside down—inside out and back to front, both ‘literally’ and figuratively!”

In magazine headlines about Westwood’s death, she has also been credited with “making punk mainstream”—a statement that seems like an oxymoron at best, and an insult at worst. Not only is punk’s “do it yourself” ethos impossible to mass manufacture, but it has always been defined in opposition to dominant culture. To celebrate its assimilation is, in a way, to celebrate its demise. But these conceptual tensions have always been at the core of Westwood’s work, and that of any creative who has profited from the popularization of a subculture they are a part of.

Growing up working-class, Westwood first made clothes out of necessity, and intended to pursue a career as a teacher—that is, until opening SEX, a boutique on King’s Road that she ran alongside her then-boyfriend, Malcolm McLaren, manager of the Sex Pistols. Standing out against the pristine storefronts that surrounded it, SEX sold handmade designs by Westwood and employed other creatives, becoming a cultural hub for London’s burgeoning punk scene.

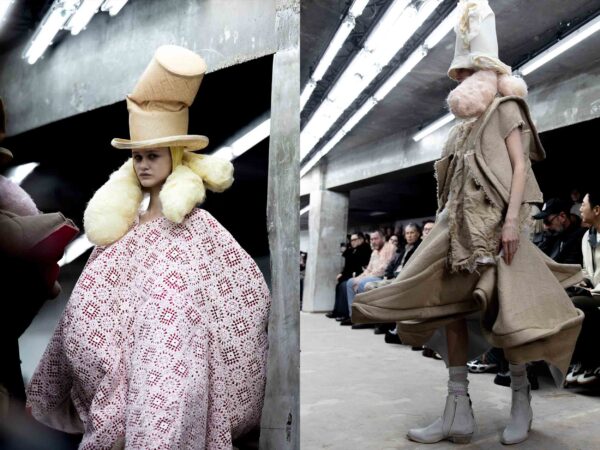

Influenced by leather-clad bikers and the aesthetics of fetish subcultures like bondage and S&M, Westwood’s early designs signaled rebellion against polite society. Her DIY approach was evident in hand-wrought details like distressed hems and garments held together with legions of safety pins—insurgent elements that Westwood often paired with tartan, a “traditional” fabric that was given a new life through its association with her work. In altering clothes, Westwood made them her own—and in donning such designs, others saw an opportunity to express themselves. Westwood’s relationship with McLaren influenced the Sex Pistols’ music, and her provocative clothing (which the band donned for their first show) reflected their radical politics, cementing her in the aesthetic canon of punk.

“Westwood’s reputation as a maverick was cemented by her own well-documented rebellious streak: From impersonating Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher on the cover of Tatler, to meeting the Queen with no panties on.”

In the years since it rose to prominence, punk has been declared dead time and time again—notably by Westwood and McLaren’s son, Joe Corré, who burnt over $6 million dollars worth of punk memorabilia in a “funeral pyre” on the banks of the Thames in 2016, to protest how it has been co-opted by the mainstream. These questions have been raised from within the movement, as well; one need not look further than the TikToker who proclaimed to have “academically studied punk,” and was subsequently bullied online, to see how institutional recognition of the movement’s impact runs counter to its core sentiment. Each time a subculture is popularized, the legitimacy of its members are called into question, leading to questions like, ‘Is it punk to gatekeep being punk?’

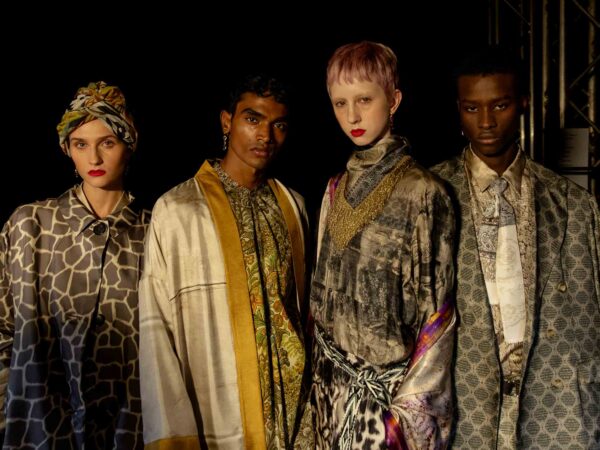

No matter how you feel about the commercialization of punk, it’s hard to contest that its ethos of disruption has seeped into today’s culture, changing our attitudes around everything from art to advertising. That these qualities are now emulated by the mainstream is an inevitable stage in the life cycle of counterculture: A movement makes people reconsider the dominant norms of the time, garners recognition, and becomes re-absorbed and perhaps even weaponized by the forces it once aimed to oppose.

The tension between fashion-as-social-critique and the inherent inaccessibility of couture is one that Westwood has confronted throughout her career. As a climate activist, the designer spoke out against the negative impact of hyper-consumption, urging people not to “buy too much” of her clothing in a 2007 interview. The same year, she released an eclectic manifesto narrated by more than 20 characters—from Alice in Wonderland to Pinocchio—that outlines her views on the relationship between art, culture, and consumerism.

Westwood’s name is now beloved within the industry she aimed to disrupt, but she was “never interested” in being remembered as an icon. As she stated cheekily in one interview, filmed during her twilight years: “Ten years after I’m dead, nobody will even remember! It doesn’t matter; I don’t care. I just want to save the world and get a life.” Of course, Westwood’s trailblazing spirit will live on—not just in the fashion canon, but also in the next generation of designers who dare to challenge it, inventing new aesthetics and forms of dissent in the process. After all, “Orthodoxy is the grave of intelligence,” Westwood often said, quoting the philosopher Bertrand Russell. “If you accept that something is right, just because everybody believes it, then you’re not thinking. You have to look at other points of view and then make up your own mind.”