For Document’s Winter/Resort 2023 issue, the design deity and extreme performance artist reminisce on the teen degeneracy that informed their creative trajectories

From the Dionysian depths of the sociosexual underworld to the Apollonian heights of his half-billion dollar fashion venture, Rick Owens straddles worlds like Hercules. How he got there is a story that can’t be told too often, because there are lessons in its celebration of other times and places, and in the transformations and transgressions that shaped it. “I wanted to be an example [of the fact] that something else—something more, something otherworldly and magical—is possible,” Owens offers. “I needed to promote cheerful degeneracy as much as I could.” In certain quarters, the people who populate his past are legends.

Ron Athey is one such. For convenience’s sake, he’s labeled an “extreme performance artist.” Better to look him up on Wikipedia yourself to appreciate the limitations of that label, even as it hints at the furiously confrontational and transcendent nature of his work—to put it simply, blood rituals with top-level shock value, inflicting the violence that characterized the AIDS crisis upon his own body. Owens knew Athey from LA’s queer fringes of decades past, and now, they get the chance to talk for the first time in a while.

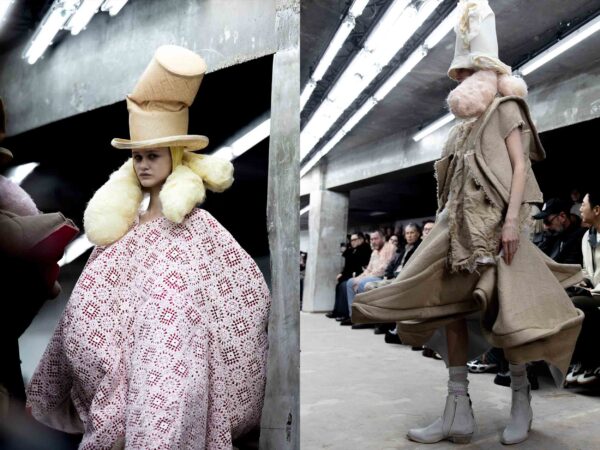

It’s hard not to see aspects of Athey’s aesthetic in some of Owens’s equally transcendent presentations—flaming funeral pyres, exposed male models, hardcore soundtracks, and so on. I was looking forward to revelation, but the conversation was a little truncated—I’ll take it as an appetizer. Between their lifetimes, there’s a whole world to dive into. I’m taking notes.

Tim Blanks: Ron, what do you remember about the first time you met Rick?

Ron Athey: I remember him from clubbing. But I mostly remember Rick being the person who worked the most in the studio.

Rick Owens: I don’t think Ron remembers the first time. I asked him if he wanted to be an extra in some dumb punk scene in a movie. And he agreed to, but he didn’t have a ride, so I gave him one. I kind of tried to stay in touch. But at that point, Ron had interests that I don’t really know of—oh, you were working at Posers!

Ron: Yeah. That was a drug year for me.

Rick: Posers was the most authentic punk store on Melrose at the time. Ron had a lot of punk cred.

Tim: I used to go to the [Hollywood] Palladium. I saw Devo’s debut performance in LA—that would have been 1978. The Bags and The Weirdos and the Germs played. What really struck me was how extreme LA’s interpretation of punk was, compared to the art-school version of it in London. LA seemed to be a city on the rim of the world, yet it managed to take everything to the furthest extreme possible.

Rick: I would have had nothing to compare it to, because I had never seen London. I wanted to be extreme myself, so I was just happy to be in the right place.

But I didn’t finish talking about Ron. We didn’t see each other for a while; we went in different directions. Ten or 15 years later, our circle of friends started to connect more—Vaginal [Davis] and Rick Castro and Glen Meadmore. We were going to Club Fuck—Ron was part of that. He was a go-go boy then, and I feel like his performances gradually turned into what he’s known for today.

Tim: In the 10 years between that first meeting and reconnecting at Club Fuck, what kind of journey were you on?

Ron: Some of it was rehab. That’s why Club Fuck was so important to me. It was a way back in, without being disruptive.

Tim: Did you feel that you had a new lease on life? A way of owning yourself?

Ron: Absolutely. LA was so intense at the end of the ’80s. It was kind of dull. Everyone was getting pierced and tattooed and corseted, and suddenly there was somewhere to show off.

Rick: All of the piercing and body work—wasn’t that a reflection of AIDS?

Ron: It was like claiming the body while it was still there. People were getting massive back pieces, up until they died. That was really an affirmation of, I’m here, I’m loud—the beginning of Queer Nation.

It was an important expression at a time when everybody was sick and dying, and you [were going to Cinematheque 16 to] shake it out every Sunday night. That venue is legendary, but it only held 100 people. I remember, one night, Madonna came and wanted to go to the VIP room. It’s like a barn in there.

Rick: I forgot Madonna went there. That is funny. Good for her.

Ron: And Pat Ast. All kinds of random people, right?

Rick: Pat Ast was there? Oh, I love that. Did Holly Woodlawn ever go?

Ron: I’m not sure, but I met her around that time at Cinematheque. Peanuts held, like, 600 people, but there were bigger show budgets at Cinematheque, so the performances were better and the audience was a little more random.

“There was a glory hole at the bowling alley in Simi Valley? I guess that makes sense. That’s where a glory hole is needed most.”

Rick: Did you ever go to that club on La Cienega? It was a gay club—Odyssey.

Ron: I went to Odyssey and Gino’s II. Everything changed after Reagan came in. Suddenly, there weren’t all-ages, all-night discos. But in the late-’70s through the mid-’80s, you’d go to catch one: Odyssey, Gino’s, Marilyn’s Backstreet Disco, on and on. There were, like, 15 clubs open till 5 or 6 a.m., seven days a week. You’d go to high school and get no sleep.

Rick: I went to Catch One on Crenshaw—that was my favorite. The music was more intense, and the dance floor was vast.

Did you ever go to Revolver?

Ron: Sometimes. I wasn’t so Westside. I think I started understanding that monoculture isn’t that interesting, but [Revolver] mixed old leather fags with downtown arts people with queer, hardcore punk boys. It was, like, forcing them to pile together. Vaginal Davis and Sean DeLear had an act. You helped make their clothes. We did everything to get them on that stage.

Rick: Someone’s doing a book on Sean DeLear; they found his diaries. They asked me to do a foreword. I’ll send it to you. But you can’t share it, obviously.

Ron: I read from that diary. It’s a profound document of the first Black family to get a house in Simi Valley—it broke rental codes. The DeLear family playing golf on the weekend… And the glory hole at the bowling alley.

Rick: There was a glory hole at the bowling alley in Simi Valley? I guess that makes sense. That’s where a glory hole is needed most.

Ron: In the ’70s, there was a glory hole anywhere there was a wall.

Tim: What was sex in the scene like then? You would go somewhere every single night. It was dirty and hygienic [at the same time]—the opposite of your upbringing. You said that you were a pig.

Rick: I said that?

Tim: You said that.

Rick: That sounds like me. It was easy to pick up at Odyssey. There was also the King of Hearts and the Meat Rack. I don’t know if you did those—I don’t remember seeing you.

Ron: I didn’t go until later. It had basic plumbing when I went. I was more drawn to the Eastside, the music scene. I was with Rozz [Williams] from Christian Death, and then, Kid Congo [Powers]—he was in [Nick Cave and] the Bad Seeds.

Rick: Were you Rozz’s boyfriend? I never knew that.

Ron: He was my first boyfriend. I was 18, and he was 16.

Rick: That is the sweetest story—teenage punk rockers.

Ron: Who became gnarly death rock drag queens. And that’s not a sexy look.

I started going to Greg’s Blue Dot on Sunday mornings with him, being like, Wow. It was hit-or-miss walking in. We were discovering a culture, a desire, instead of glamor or shock value.

Rick: I was just complaining that Paris doesn’t have [a place like that]—they don’t have that scene. In London, they have a good, healthy scene.

“I don’t think everybody should be like me, but I also don’t think everybody should be themselves. Somewhere in the middle is fine, but some people who have to be extreme to keep the balance right.”

Tim: Ron, when you met Rozz Williams, were you slightly in awe of him?

Ron: I met Rozz in South Pomona. Christian Death was rehearsing in a garage, and they had never played. I didn’t think, Oh, this is really a straight punk scene, or whatever—but we were the two strange-creature gays. We had chemistry immediately. We were practically making out the minute we met. We lived together for three years in his parents’ basement, Little Tokyo Hotel, American Hotel—different places around LA.

Rick: What were you doing in Claremont?

Ron: Well, if you’re from Pomona, Claremont is this fancy college town full of parties and Quaaludes. I was in a science program that dropped us off there every week. I worked at the Jonas Salk Institute.

Rick: Oh my God.

Ron: Claremont kids are more posh, so the ones who went to boarding school were already punk by ’78—in a more British way. It was our entrance to a scene.

More than 10 years ago, Rozz committed suicide.

Rick: Had you split before that?

Ron: Yeah, we’d split up after three years.

Rick: This is none of my business, so stop me when I get too intrusive.

Unknown: Ron, are you gonna be done in 10 or 15?

Tim: No! Was that to give Ron the opportunity to say, Yes, we’re gonna be finished soon? It’s like a bad date. You know, when you get the phone call.

Do you have somewhere to be in 15, Ron?

Ron: Yes.

Tim: Then I have to get to the meat, which I want to know from both of you: Talk about how your upbringings made you who you are today—your religious backgrounds.

Ron: Mine’s Pentecostal. I think it’s my obsession with, How do you enter ecstatic states [without] the blood of Christ? I still practice glossolalia with singers and experimental vocalists—somewhere between opera and Yoko Ono. I look at the audience as a collective witness. That’s why I do the art that I do. I don’t see myself as an entertainer. I’ve never wanted to be mainstream, yet I have a bloated sense of self-importance [laughs].

Sometimes I identify as a mystical atheist; like, I’m still obsessed with spirituality, with esoteric Christianity, with queer theology. It still always comes down to those stories, no matter how far I go in other directions.

I think in a lot of the artwork I do—because I’m an art-life person—it’s all queries: answering esoteric or philosophical questions in visual ways.

Rick: Was there a catalog for your retrospective in LA, [Queer Communion]?

Ron: There’s a monograph called Pleading in the Blood. It’s a coffee table book.

Rick: I did a retrospective a few years ago. It’s the most satisfying thing.

Ron: It makes it all worth it.

Rick: It’s a thrill to see everything collected and composed in your own personal [way]. I called it ‘the perfect obituary.’ Because that’s how you’re going to be remembered—you control how you’re going to be remembered. I thought I was being very clever then. But I realized that everybody’s Instagram feed is now their obituary, and so we all get the same satisfaction, in a way. It’s for public consumption.

I faced a lot of judgment and a lot of bullying when I was young. So I wanted to be an example [of the fact] that something else—something more, something otherworldly and magical—is possible. I wanted to counterbalance severe judgment and moralism. I wanted to be the opposite of that. I don’t think everybody should be like me, but I also don’t think everybody should be themselves. Somewhere in the middle is fine, but some people who have to be extreme to keep the balance right. I felt like I needed to promote cheerful degeneracy as much as I could, but you can’t indulge yourself and go too far, because then you’re just dismissed. If you are palatable enough, you can infiltrate and influence culture and society a little bit more.

Tim: For both of you, the ceremonial aspect of your work feels very atavistic—and that is surely deliberate.

Rick: I was seduced by the exoticism of ceremony and Catholicism. And what I think when I look at you, Ron—I feel like you are influenced by that search for transcendence and ecstasy from your religious experience. We didn’t have that.

Ron: Also, just the funeral march. I do think fashion plays [a role in that]. I don’t know. I see pageantry.

Rick: I was all about anger. I’m all about anger and revenge.

Ron: I love revenge. Why forgive when you can get even?