Was Gore Vidal’s objection to being defined as gay intellectual—“post-gay” before his time?—or was it personal, rooted in the sexual mores of a different generation? Writer Tim Teeman takes us back to 1960s Rome, to Vidal’s sexual paradise.

He once said he’d had sex with a thousand men by the age of 25. Gore Vidal loved sex, but hated labels; a gay man who never defined himself as gay. The bestselling author and commentator, who died, aged 86, in July 2012, never came out. For him, gay and homosexual were redundant, meaningless categories. This master of American letters said he was bisexual. He told me, when I interviewed him in 2009 in the Times of London, that the only rule of his 53-year relationship with partner Howard Austen was “no sex.” “People can’t believe that.”

Was Vidal’s objection to being defined as gay intellectual—“post-gay” before his time?—or was it personal, rooted in the sexual mores of a different generation? Or was it both, and much more besides? How Vidal saw his sexuality, and why he saw it as he did, is the foundation of my book, “In Bed with Gore Vidal: Hustlers, Hollywood, and the Private World of an American Master.” Using fresh interviews with his family and friends, including Susan Sarandon and Claire Bloom, it interrogates the true depth of his relationship with Austen, his enduring love of a boy from boarding school, his sex with hustlers and Hollywood stars, the true nature of his relationships with women, why he didn’t take a more visible campaigning stand on gay issues and HIV, AIDS and how his sexuality influenced his personality, work and public life. The book also reveals Vidal’s painful decline into alcoholism and dementia, which wrecked his mind and close relationships in his final years.

If Vidal intellectually objected to being categorized personally, he had also experienced what he felt as rejection after publishing “The City and the Pillar” in 1948, the first contemporary American novel to deal with homosexuality. Vidal enjoyed the fame it bought, but felt the literary establishment rejected him afterward; he also felt his homosexuality had disqualified him from a political life: He ran unsuccessfully for public office twice and desired, deeply, to be president. “Gay” for him meant marginalized and powerless, and Vidal aligned himself, from his entitled childhood onward, with the powerful, including friendships with John and Jackie Kennedy.

“This sex for money and favors was sort of a common thing to do. You knew where these guys were and you got to know them and they’d introduce you to others, so you’d have a whole social life.”

Yet he was no hypocrite: In the 1960s and 1970s, when gay standard-bearers were few, Vidal, while not holding banners or outing himself, wrote strong essays advocating equality and supported gay organizations. He was verbally abused as a “queer” on national television by conservative commentator William F. Buckley in 1968. Vidal’s sex life and sexuality were as complex as anything else about him. When I asked him if he was happy, he replied, quoting Aeschylus, “Call no man happy till he is dead.”

Vidal’s sexual gallivanting reached a zenith when he and Austen settled in Rome in the early 1960s so Vidal could have use of the library at the American Academy to research his bestselling novel “Julian.” In that period, mid-“Dolce Vita” when Rome was embracing the glamorous café society popularized by Federico Fellini’s 1960 film, the city “was a very good place to meet really attractive young guys willing to do anything. That was another big point of the Rome move,” says Matt Tyrnauer, Vidal’s good friend and one-time editor at Vanity Fair.

Cruising for sex in Rome was “the best it could have been for them,” longtime friend told me. Vidal and Austen would go to the Pincio, [a hill near the center of Rome] where the hustlers gathered. They had a Jaguar convertible, which was surrounded by young men. “Italians are very innocent and sincere to this day and obviously, besides seeing these rich guys, they’d want to talk about the car. I asked Gore what his line was and he said, ‘I’d try, “You’re the most beautiful boy I’ve ever seen,” and see how that works.’”

To Sean Strub, founder of Poz magazine, Vidal asked, “Do you know the difference between American boys and Italian boys? Italian boys have dirty feet and clean assholes, and American boys have clean feet and dirty assholes.” He also repeated to Strub his contention that “he had sex with hustlers in the afternoon, so in the evening he could focus on conversation rather than cruising.” The couple would take one or two young men to the penthouse at the Via di Torre, 21 Argentina, where they lived. The sex, the friend says, was conducted separately. Vidal’s type was “basically a straight masculine guy.” In his memoir “Palimpsest, ” Vidal wrote that he was sexually active, never passive.

In 1961, Vidal said Rome was “a sexual paradise.” The literary critic Richard Poirier, a friend of Vidal’s, told Vidal’s biographer Fred Kaplan that Italian gay life was “very seductive. It was sort of older to younger brother. This sex for money and favors was sort of a common thing to do. You knew where these guys were and you got to know them and they’d introduce you to others, so you’d have a whole social life. That was perfect for Gore, and he liked the types, the Italian boys who were available. In Rome it was the practice to take the boys back to the apartment. He’d pay them and give them clothes.”

Vidal told Donald Weise, who published his book of essays “Sexually Speaking,” that “every last one of the boys we knew in Rome are fathers and grandfathers now. But they weren’t just lying there. They were eager participants in a normal activity.”

The theater director David Schweizer visited Vidal and Austen in Rome in 1971, the year after Vidal’s autobiographical novel, “Two Sisters,” came out. Schweizer was a 20-year-old Yale student and the then-lover of Tennessee Williams. In the taxi, Schweizer recalls, Williams “was babbling, ‘I don’t know if I have the strength for Gore. You know he’s so full of himself. Baby, you know he can’t write—he could never write.’” Williams’ relationship with Vidal was rooted in deep affection, despite occasional squalls.

“My first impression of Gore was standing at the top of his stairs. I’m a small, compact man and my impression of him was of a giant,” says Schweizer of meeting Vidal for the first time. “He seemed so tall: big chest, long legs, so handsome and deft. Dazzling.” The sex chatter at a restaurant was “who was a top or bottom, a little cock or big cock. Gore took a liking to me, it wasn’t sexual. I found him incredibly compelling. I would have snuck out in the afternoon and thrown myself on him in a second.” His attitude toward sex fascinated Schweizer, who, even coming out at a “wildly promiscuous” time, still believed in a “romantic taint” to homosexuality. Vidal was far more “clinical, he lined people up to have sex with every day.”

Vidal invited Schweizer to afternoon tea, where his tone was “brusque, tough love.” “We would talk politics and suddenly Gore would say, ‘Now it’s time for my afternoon …’ and some gorgeous young man would walk in. They were very high-quality trade, extra-presentable, their beauty was aristocratic and some were American. Gore insisted it was paid-for sex.” Schweizer asked him why. “That’s the way I want it.” But why, Schweizer persisted. “It becomes only itself. It is what it is,” Vidal replied, meaning, Schweizer interpreted, ‘“It’s a service, it’s an activity, I am pleasured and someone is rewarded.’”

“Italians are very innocent and sincere to this day and obviously, besides seeing these rich guys, they’d want to talk about the car. I asked Gore what his line was and he said, ‘I’d try, “You’re the most beautiful boy I’ve ever seen,” and see how that works.’”

The young men he hired seemed very handsome, Schweizer said to Vidal. “Yes, of course, they have to be,” said Vidal. In “Palimpsest,” Vidal writes that Italian “trade has never had much interest in the character, aspirations or desires of those to whom they rent their ass.” “Do you ever get involved with any of them?” Schweizer asked him. “No, why would I?” Vidal replied, aghast. “It would be hard for me not to,” said Schweizer. “Oh, you’d better get over that: it doesn’t make any sense,” said Vidal. “Well, it makes sense to me,” said Schweizer. “Well, my way is my way,” said Vidal. “It suits my life and will never be any other way.”

Schweizer asked him what Austen meant to him. “He’s my companion, we’ve never had sex,” said Vidal. “Even when you were both young and cute?” asked Schweizer. “I needed someone I could trust,” Vidal replied simply. Schweizer today admits he found Vidal’s attitude “so perplexing, but I liked he was so candid. There was something so vehement and legitimate about him, I accepted what he said. My radar was always up for a slip, a contradiction, a chance to say, ‘You say that, but you just did this …’ but it never happened, and I trusted him.”

Vidal was less sexually inclined than Austen, says Bernie Woolf, who knew Vidal in Rome in the 1960s. “Howard was very promiscuous. He picked up sailors, he worked the streets and picked up trade. George [Armstrong, a friend of Woolf and Vidal] was a procurer of sorts and very friendly with Gore. He had a million tricks. Rome was a very advantageous place to live: If you were a homosexual of a certain age at that time you could have almost anybody. I don’t mean all the young men were gay, but for 500 or 1,000 lire they were yours.”

“I think Gore and Howard had a shared sex life, but as in all things Gore was boss and Howard the facilitator,” says Tyrnauer. “It was an open relationship in which they relied upon what they referred to as ‘trade.’ I heard the word from Howard mostly: in Ravello [where Vidal and Austen moved in 1972] he would point to some of the locals and say, ‘He’s trade, he’s not trade.’” Austen boasted about having sex with multiple generations of the Ravellaise, the fluid nature of Italian male sexuality matching Vidal’s theories.

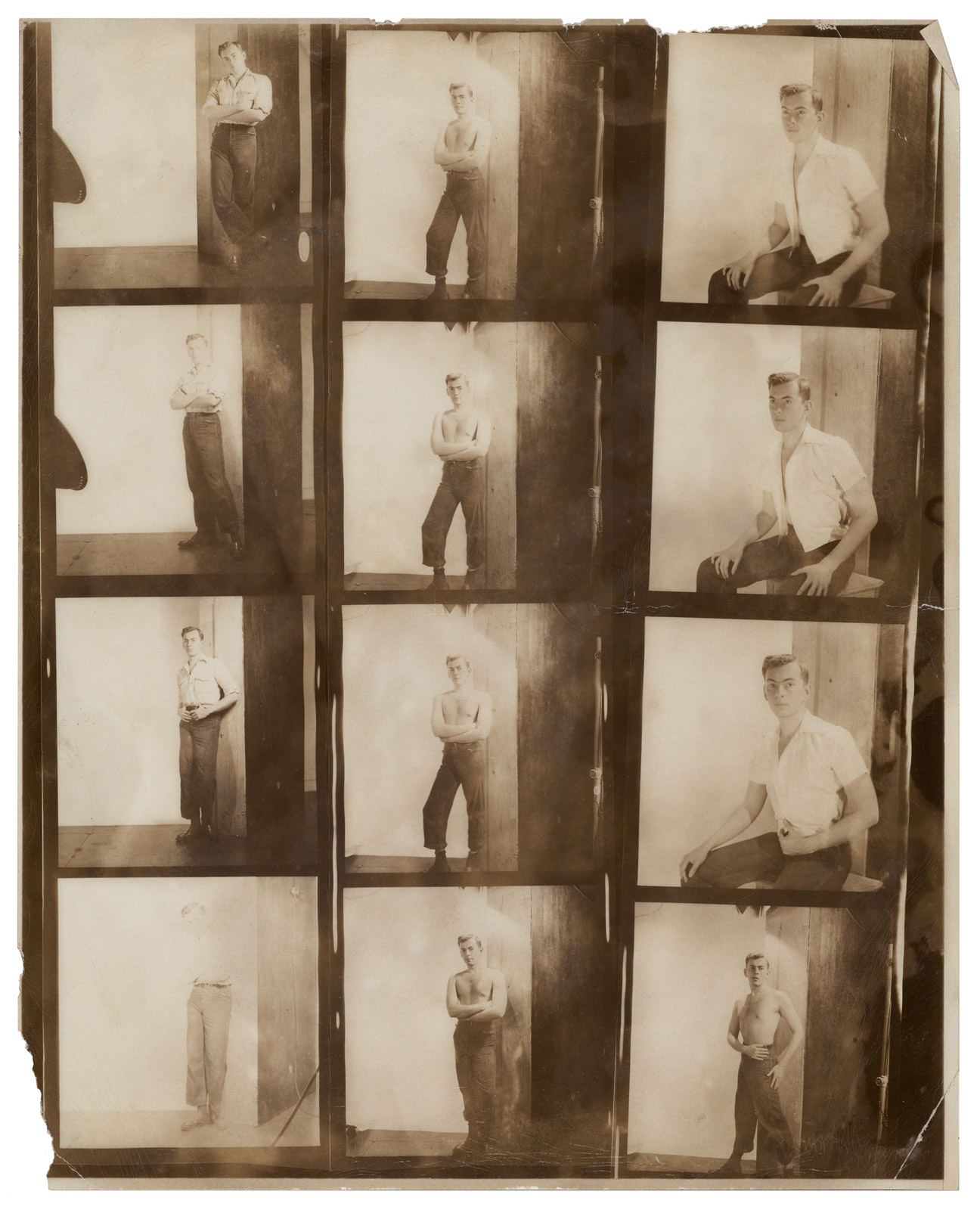

Dennis Altman, Vidal’s friend and author of “Gore Vidal’s America,” visited Vidal and Austen at their Rome apartment. “Gore opened the door and, with a big wink said, ‘Would you like a pre-dinner appetizer?’ He took me to a bedroom where there was a rather attractive Sardinian boy lying on the bed. It was clear the boy was available. Gore would provide and you would pay. The assumptions were quite extraordinary; I don’t know how he would have reacted if I had said, ‘I don’t want to have sex with this guy.’” In Ravello, on the beach, there were guys hanging around who were “obviously” available, recalls Altman. “Gore would say, ‘Are you interested in any of these boys?’ He would pick up the ones who were available.” “Gore’s sex drive was tremendous up to 55 to 60,” Fred Kaplan tells me. “He was extraordinarily good looking, he used his good looks and was very aware of it.”

Altman thinks Vidal used prostitutes “as a way of maintaining total control and also to deal with his own rather confused attitudes towards his own sexuality. He said he was bisexual, but he clearly wasn’t in any real sense. There is no question his sexual interests were not with women, but men and specifically in ‘trade’ or ‘rent.’ He liked young, good-looking working-class men, an old English tradition Gore seemed keen to take over.”

Rome would always be special for Vidal. In a 1992 letter to his friend Judy Halfpenny, he said, “I was never lovelier, as Marlene used to say with absolute seriousness glaring at old stills, than when I was in Rome … I was 47. I still worked out at a gym and there was sex and motive. At 60 I said to hell with it and now people make most unkind references to my lack of beauty. I find myself peculiarly unbothered, so much for vanity, which is only useful, necessary if you’re after something. No pursuit, no beauty. I’m a utilitarian finally.”

A Sexual Paradise first ran in Document Fall/Winter 2013.