Director Sam Shahid joins photographer Bruce Weber to discuss the artist’s clandestine homoerotic nudes, documented in his new film ‘Hidden Master’

George Platt Lynes photographed Jean Cocteau, Marianne Moore, Marc Chagall, and Henri Cartier-Bresson. He shot supermodel Lisa Fonssagrives for department stores in their aspirational heyday, plus many features and covers for Town & Country, Harper’s Bazaar, and Vogue, whose staff he briefly joined. As the official photographer of the American Ballet under George Balanchine, he crafted meticulous pictures of dancers on and off stage—rendering them, paradoxically, both sculptural and alive. Lynes also exhibited at galleries during his lifetime and is now well-collected by the Met, the Guggenheim, and the Museum of Modern Art. But for all his notoriety, barely known to those outside his inner circle during the height of his career in the 1930s and ’40s, leading up to his death in 1955, were his male nudes.

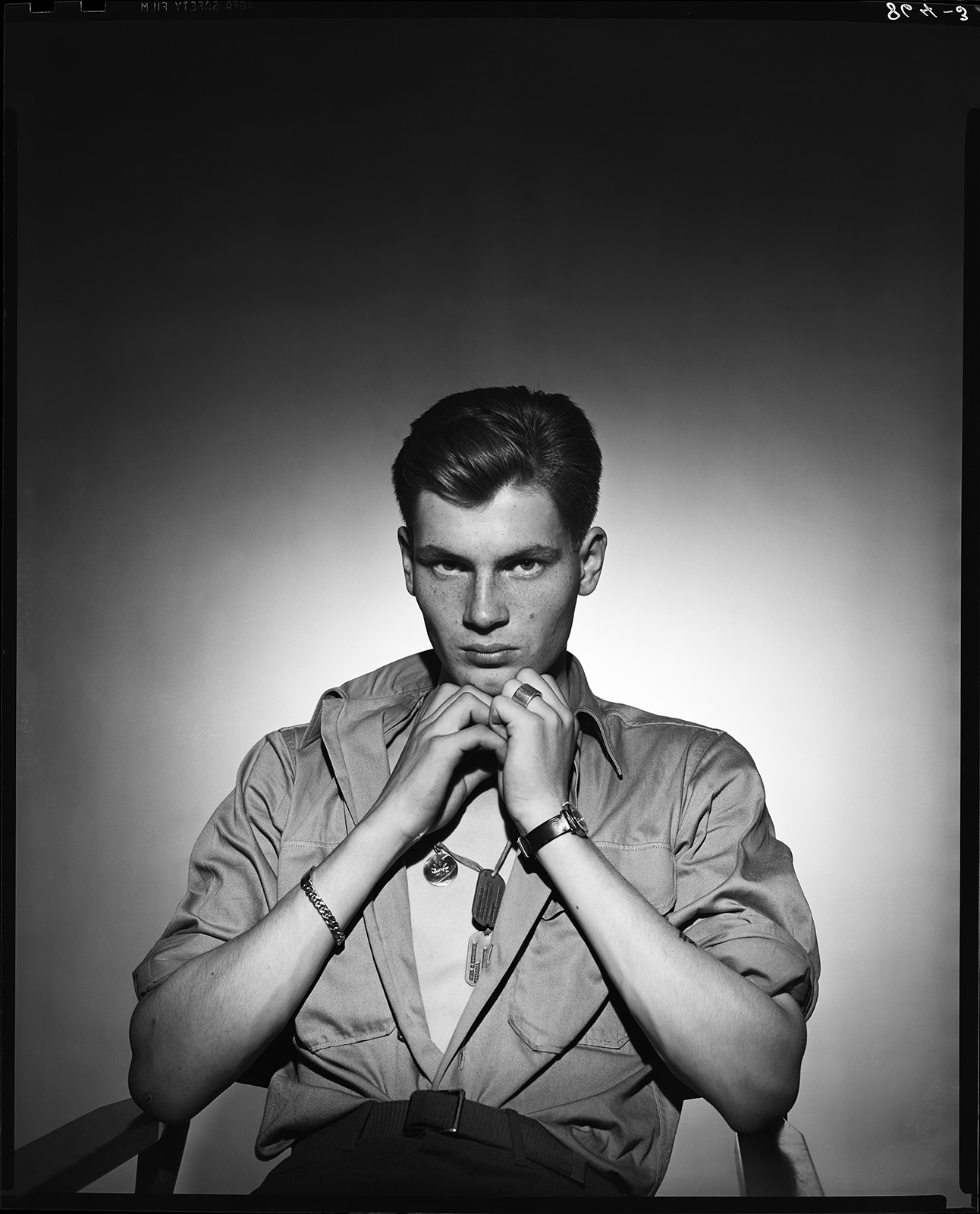

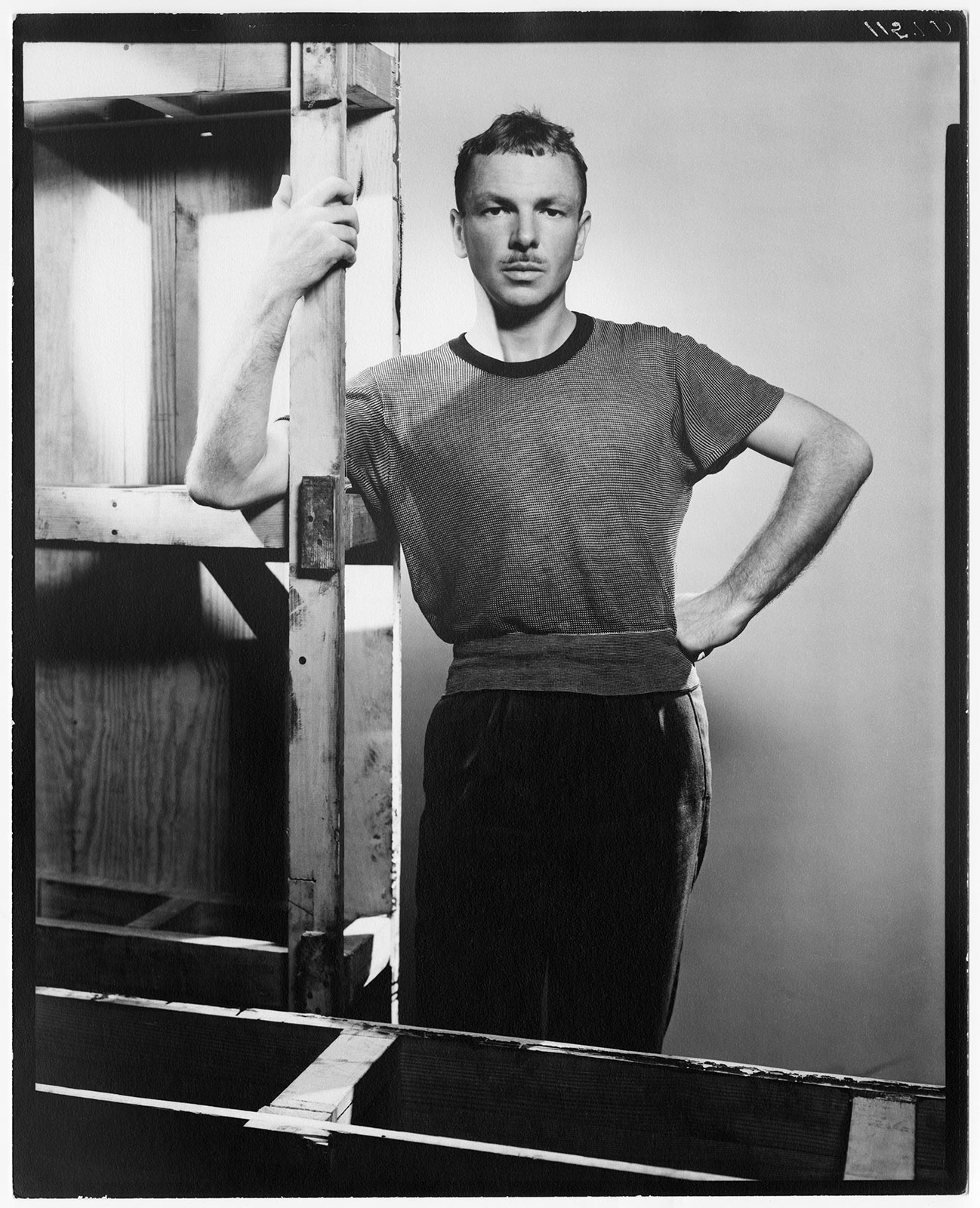

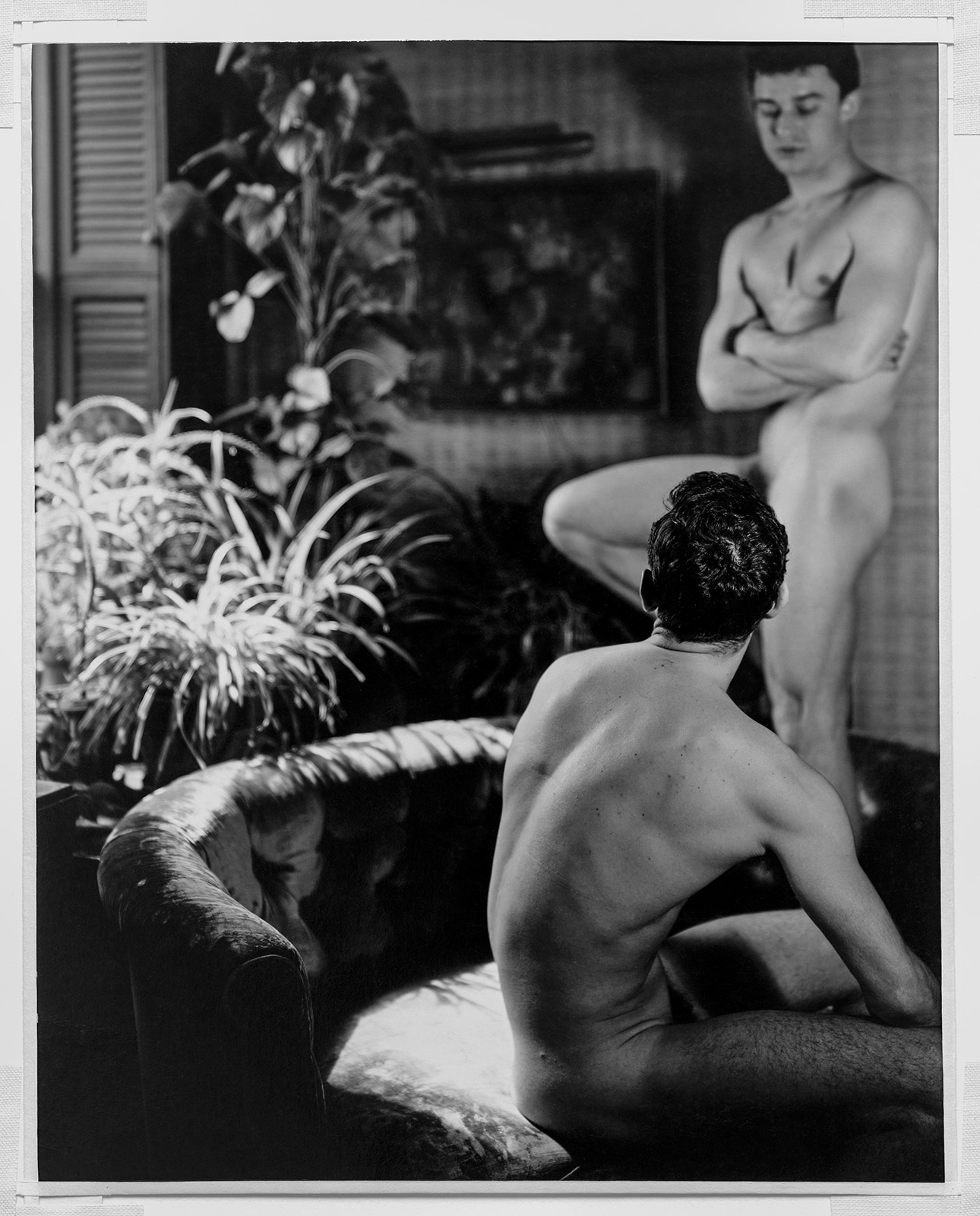

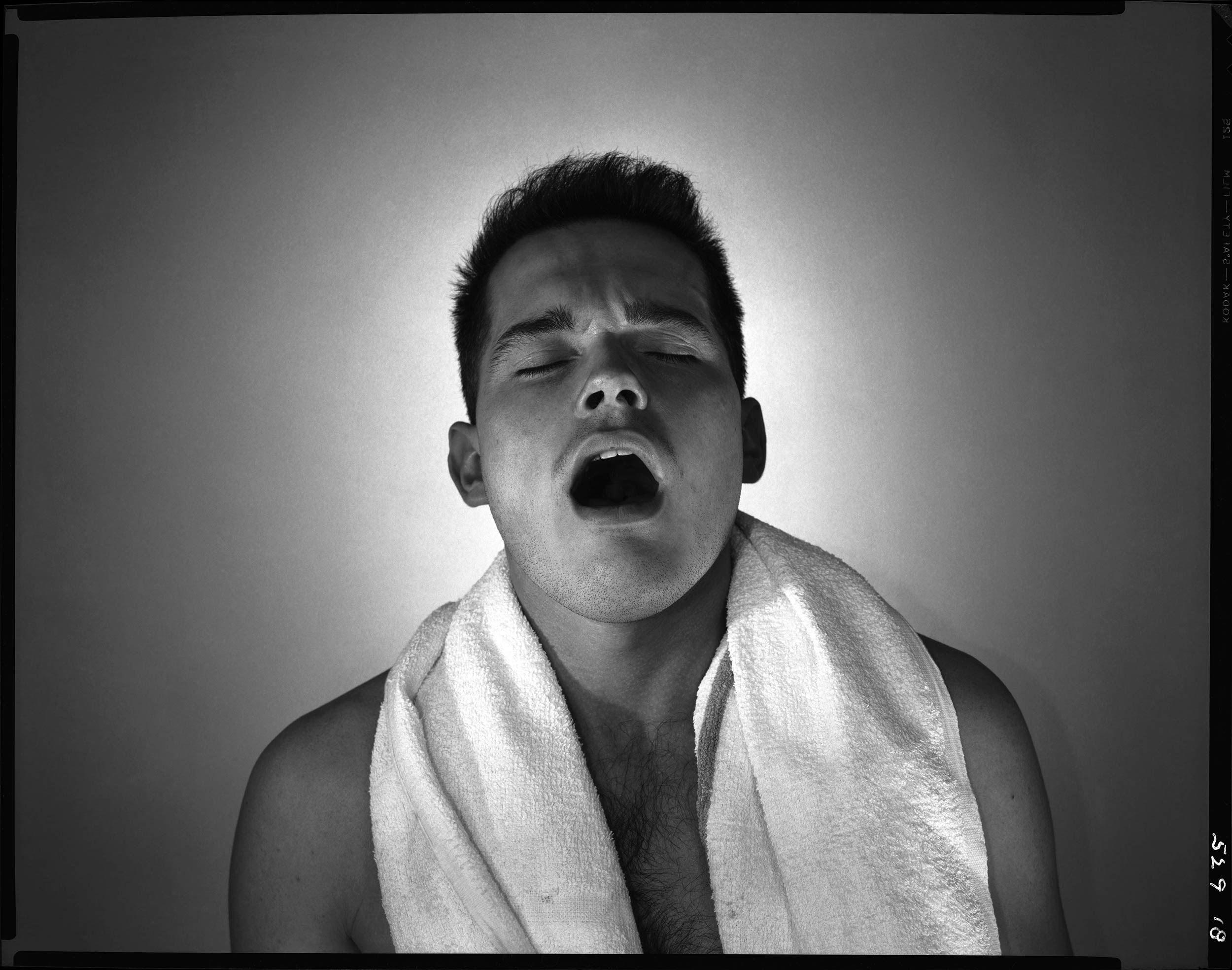

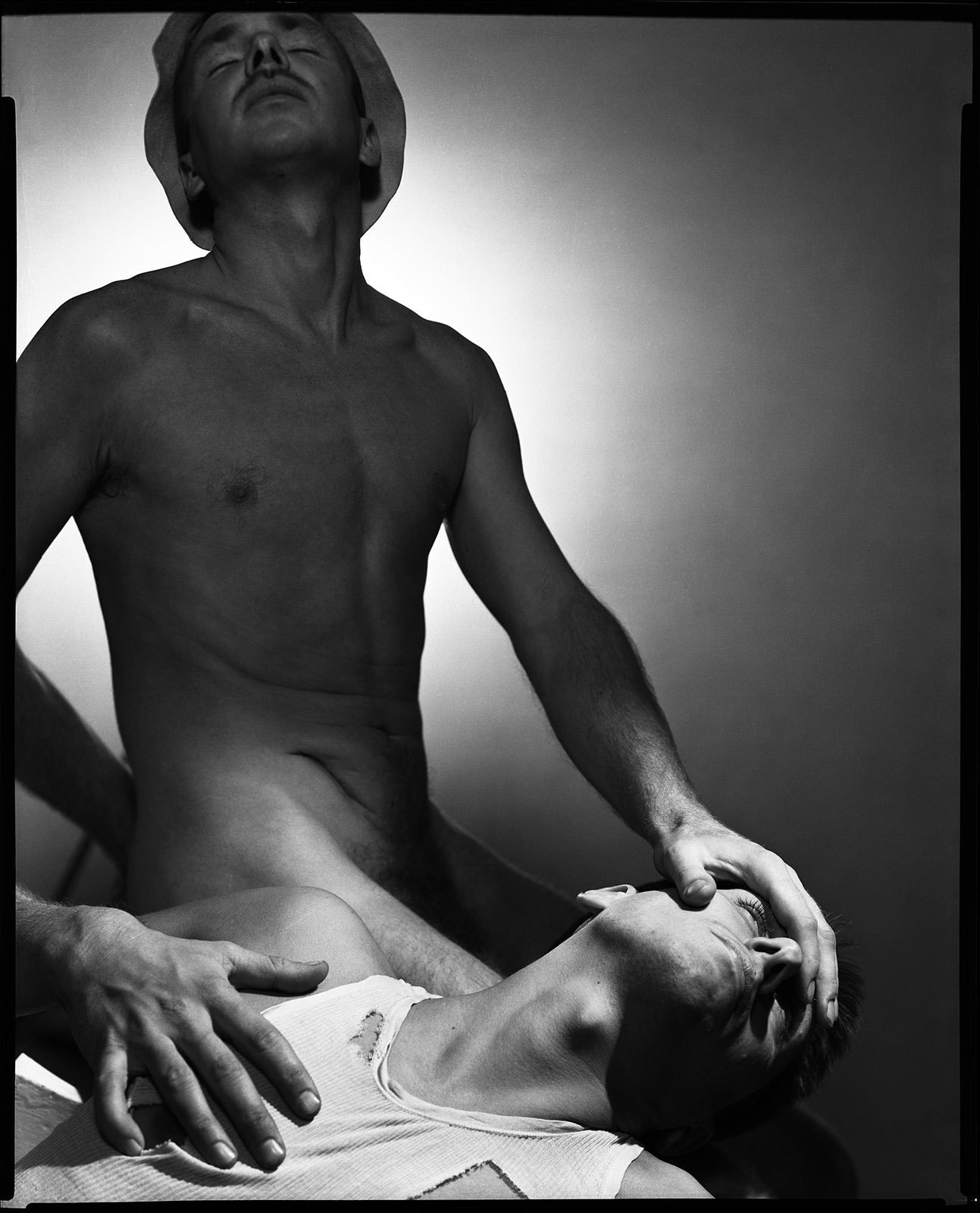

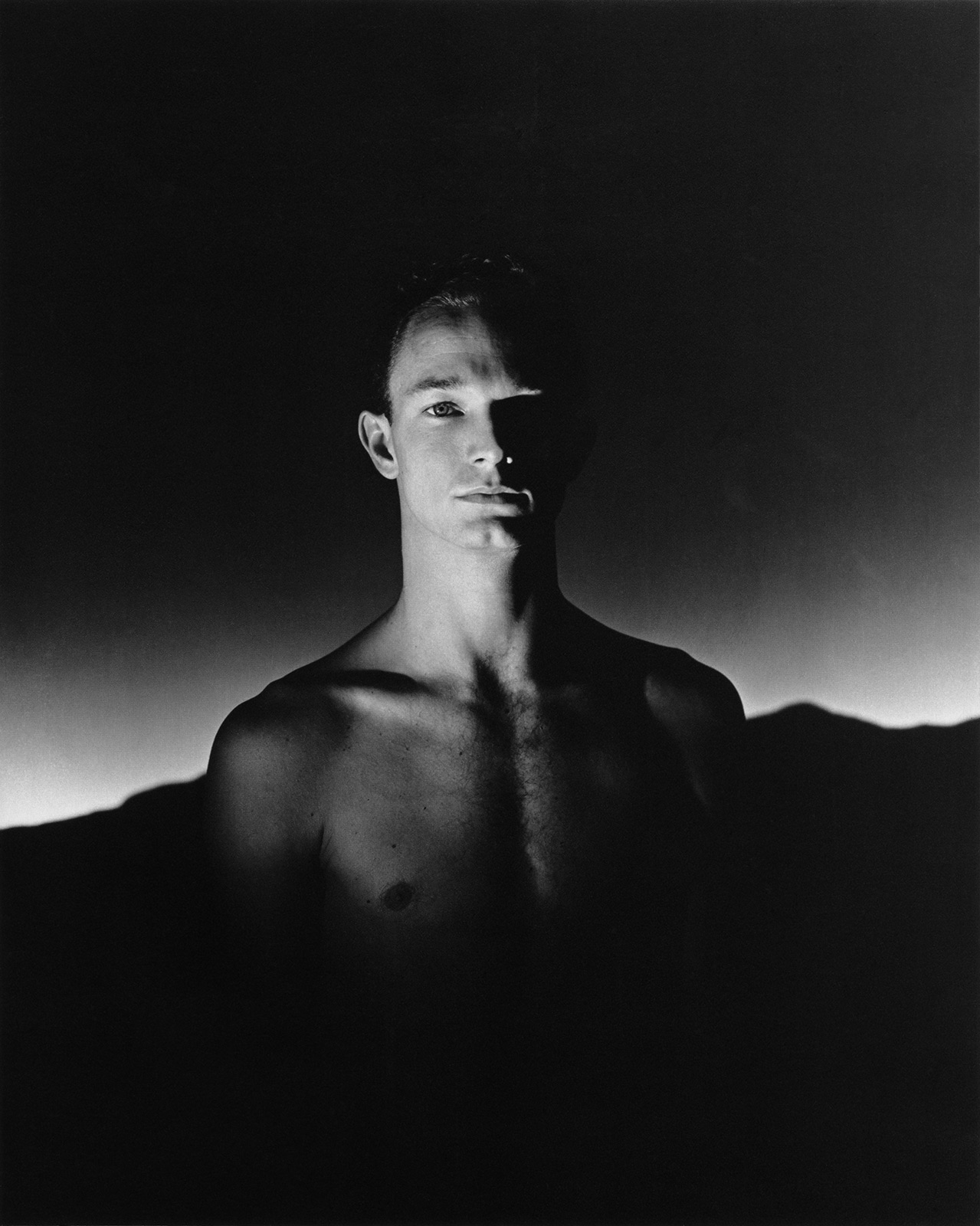

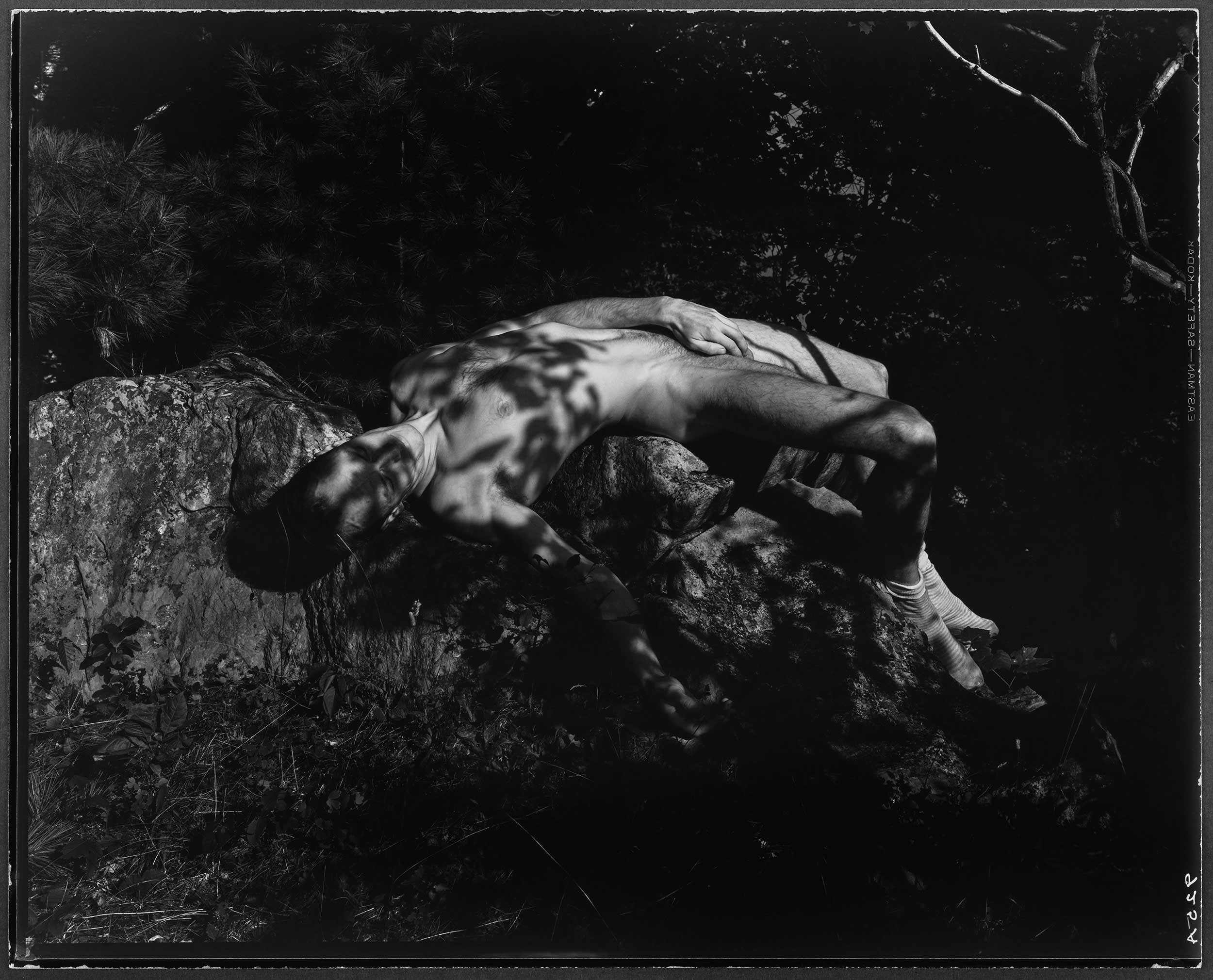

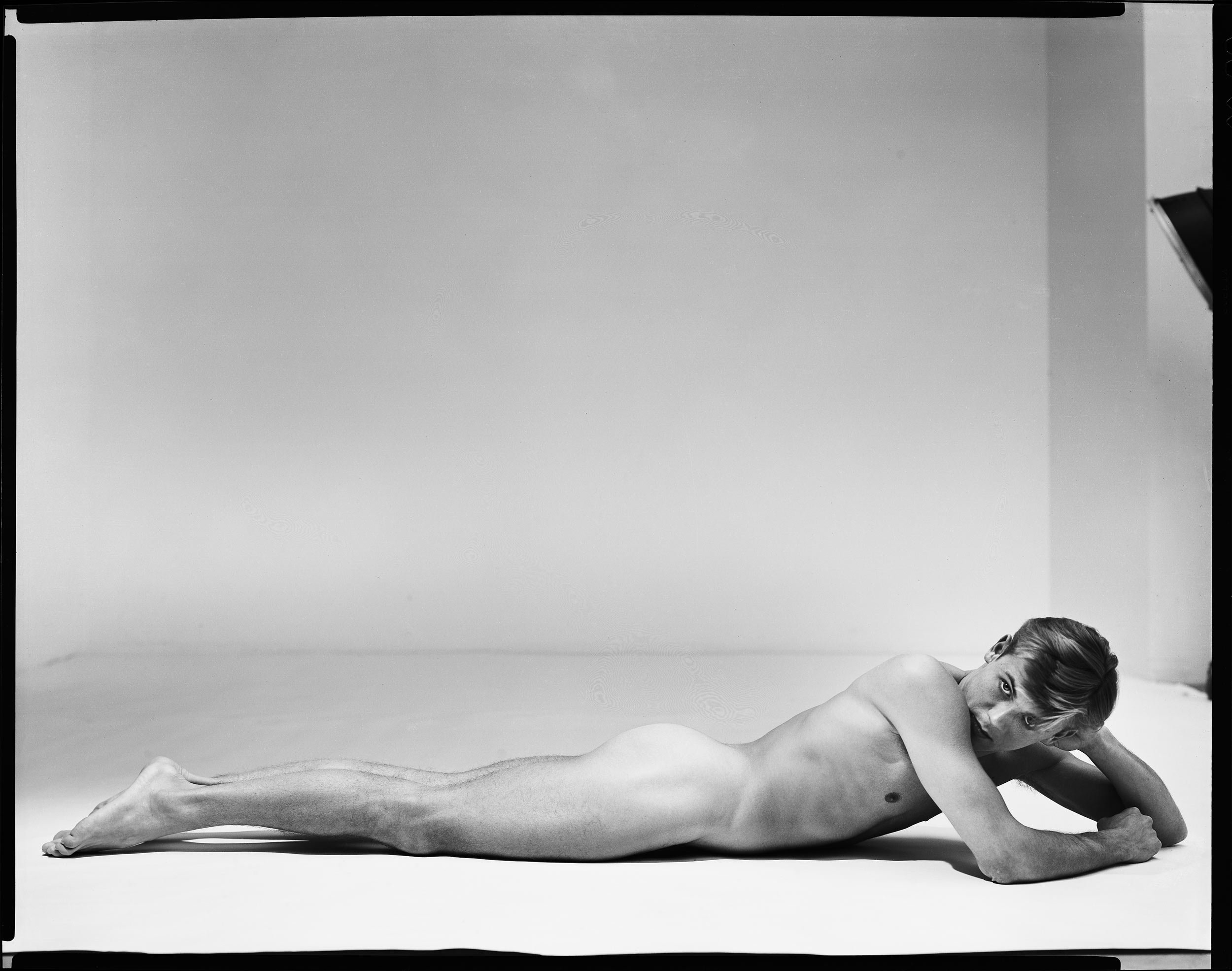

Sensitive yet sharp, formally refined yet buzzing with human connection, the sometimes explicit photos probably wouldn’t have found much currency in the first half of the 20th century. Fearful of their being destroyed upon his death, Lynes willed them not to an arts organization, but to the Kinsey Institute for Research in Sex, Gender, and Reproduction at Indiana University, where many still reside.

In the 2020s, one would like to think the culture has more appetite for such pictures—and the art world probably does. But Republican lawmakers are attempting to defund the Kinsey Institute in Indiana, while politicians in states like Florida play Orwellian games to make sure educators “don’t say gay.” It is in this strange context—when queer visibility feeds queerphobia, and gay acceptance hinges on gay desexualization—that Sam Shahid directed Hidden Master: The Legacy of George Platt Lynes. The 96-minute documentary, which has been receiving rave reviews and racking up awards on the festival circuit ahead of its wider theatrical release this spring, explores the late photographer’s life as both an artist and a social force who staged raucous parties and collaborated and/or slept with the likes of novelist Glenway Wescott and PaJaMa (the throuple and artistic collaborative Paul Cadmus, Jared French, and Margaret French).

With the adjective “hidden,” Shahid’s title refers not only to Lynes’s erotic photos stuffed in bins and albums in institutional and private archives but also to the obscurity around his personal life—despite his resounding influence on artists and photographers today. While, in the era of Avedon, Lynes’s staged and still, high-contrast images fell out of favor for cinematic shots that felt in motion, generations of artists and art historians alike have been magnetically drawn to their sensual nuances, formal precision, and rich emotionality—which feel as surprising, modern, and sexy today as they would have seemed to audiences nearly a century ago.

On a brief respite between his many screenings across the globe, Shahid rang another Lynes devotee, the legendary photographer Bruce Weber, to reveal the origins of his revelatory project.

Bruce Weber: What first drew you to George Platt Lynes’s work?

Sam Shahid: You gave me one of his photographs for Christmas, then Jack Woody came out with those books on George Platt Lynes, and that was when I was like, This work is incredible. Who is this person? I knew his name, but I didn’t know anything about his life.

Bruce: I totally agree with you. The work was extraordinary. I’ve never seen anything like it.

Sam: What really set me up for doing the film and everything else was when Rizzoli called me to see if I’d like to design a book called George Platt Lynes: The Male Nudes. I remember laying the book out and editing and designing with countless prints. I gave it to you after it was published and your response was, ‘I have never seen these images.’ I thought, Oh my god, Bruce Weber has never seen these images. That gave me the idea that I wanted to do a documentary on this man’s life and his work. Because I was overwhelmed by it. I wanted the world to see how beautiful his work was.

Bruce: What were the cultural forces behind this film? What made you think now is a good time?

Sam: I knew that a lot of people didn’t know who he was and how influential he was later with photographers. What was sad to me was that he never actually was able to see his legacy come to fruition. I thought the film would bring the legacy to the public that he always wished for because he could never show that in his lifetime. I was so surprised that there was such joy among the audiences [at the festivals].

When the The Lebanese Independent Film Festival accepted our film, I kept saying, ‘Are you sure?’ I couldn’t believe it. I took the whole team with me to Beirut. I’m Lebanese, but I had never been, and my dream always was to go. It was a nice crowd. After the screening, this guy came up to me, who also had a film in the festival, and he was in tears. He said, ‘I’m going to tell you, I’m sitting here thinking, Where am I? Am I in Paris, London, New York?’ And he said, ‘I just couldn’t believe I was out here in Beirut, seeing your film, and the contents of it.’

That Sunday morning, we planted a tree in my sister’s honor—she had died a few years ago—with her name and everything. It was the same day they had a closing ceremony. I don’t usually go to those things at the end. But I said, ‘We’ll go to this one. We came all the way to Beirut.’ But halfway through the ceremony, I said, ‘Guys, what are we doing here? Let’s go. It’s so hot.’ And all of a sudden, the president said, ‘Now the winner of the Best International Documentary Feature Film is…’ and when she said the words ‘Hidden Master,’ I ran onto the stage. I had a bad knee at that time, but I just jumped up there. My thoughts were that my sister made it all happen. I honored her that morning. And she honored me that evening. I will always believe that.

When we went to BFI Flare: London LGBTIQ+ Film Festival and sold out both shows, it was unbelievable. I just cried at the end. The audience asked a lot of questions. This guy raised his hand and said, ‘I knew Fred Koch.’ Then another guy said, ‘But he was a real staunch Republican.’ And I said, ‘Well, we discovered from the executor of the estate of Fred Koch that he voted Democrat.’

Bruce: I got to meet Fred Koch. Many years ago, he came to visit me at our loft, and I was sitting with a whole pile of photos. Howard Read, who was the photography director at Robert Miller Gallery, said, ‘Bruce, don’t show him any landscapes, any pictures of your trucks, your dogs, or your relatives. He just wants to see photographs of men.’ I thought that was quite funny. I was showing him pictures of some trucks, and I was showing some landscapes, and maybe some buildings that meant something to me. When he came across a photograph of a young man, he said, ‘Who is this? What does he do?’ And I said, ‘Honestly, he’s our pool cleaner.’ And he said, ‘He’s one of the most handsome men I’ve ever seen, I want to buy this picture.’

Sam: Fred Koch, as we know, had the largest collection of homoerotic art, but he would never ever allow you to see it, nor would he meet with you. We tried several times. What we had filmed by that point was all [Alfred] Kinsey’s [collection of Lynes photos], and a little bit from the Guggenheim. Then Fred died. I finally called John Olsen, who was close to Koch for 13 years, and handled all his businesses. We went up there to see the collection. And Bruce, you would not believe it. The house itself is like a castle. I mean, the paintings and the artworks were amazing. The collection was beautifully preserved. John Olsen, in the film, said that he’d never seen this collection and that Fred never talked about it and never mentioned anything about it, and it was all in closets or storage rooms. John was so kind and so generous, he let us take what we wanted to take with us. We brought it to New York where we had it insured. The value on it was a million and a half. We had to go back because we wanted to see more. There were things that Koch bought from Bernard Perlin, who inherited whatever George had at his time of death. And they were quite different from Kinsey’s. We learned a lot about George through that.

“I knew that a lot of people didn’t know who he was and how influential he was later with photographers. What was sad to me was that he never actually was able to see his legacy come to fruition.”

Bruce: You have a lot of characters in your film. Most people have to pick very important people to say the right things. And I liked that you had a bunch of characters who absolutely had no restrictions. People spoke the truth a lot of the time. They said their piece. I do want to say one thing, Sam, which makes me smile when I think of all this… How many years have I known you?

Sam: God, Bruce, since 1983?

Bruce: I was so young then. The reason I say this to you is because that was very typical of the artists and the filmmakers and photographers and everybody who worked like a team, and people don’t do that very much anymore. I thought about the PaJaMa series. The photographs that Paul Cadmus made with Jared and Margaret French. They used George as a model sometimes. They copied each other’s style a little bit, and they made just such magical pictures that were quite funny sometimes. People had a big sense of humor in those days. I think that Bernard Perlin’s interview in the film is extraordinary. Would you talk to us a little bit about it?

Sam: Well, actually, the first person we interviewed was George Platt Lynes’s nephew, George Platt Lynes II, and we were just getting to learn about him and it was wonderful. And then we finally scheduled Bernard Perlin, but he was a little difficult at the beginning. He didn’t want to be filmed. We went up to his place in Connecticut and interviewed him, but he talked only about himself. Then he said he was very tired. So when I got back to New York City, I said to my team, ‘Look at this, it’s all about himself. I want stuff about George, not him.’ So we scheduled again. We went there and I said, ‘I’d love to have one of your Bloody Marys.’ He said, ‘Oh, that gives me a reason to have a Bloody Mary, I guess.’ Then he talked about George. He was the only one actually, of all the people that knew George, who talked about his sexual habits. I asked all the others who knew George about what he was like sexually, and if they had sex with him, and they would say things like, ‘Oh, he was such a nice man.’

Bernard was really gracious. He was the only one that really talked. He called me and said George was a devil and everything, but he loved him—and in the film he is so great. But there was a little bit of controversy within my team, as well as a couple of filmmakers who saw the rough cut [about the explicitness]. John Olsen loved it. But he showed the film to the board members of the Koch Foundation, and they were mortified.

Bruce: I can see part of what attracted you to this was the personal courage you have to show what’s behind something. I think that that’s pretty spectacular. We’re all thankful that we’ve had these experiences with you, Sam—you really bring life. I appreciate you doing it.